China launches quantum-enabled satellite Micius

- Published

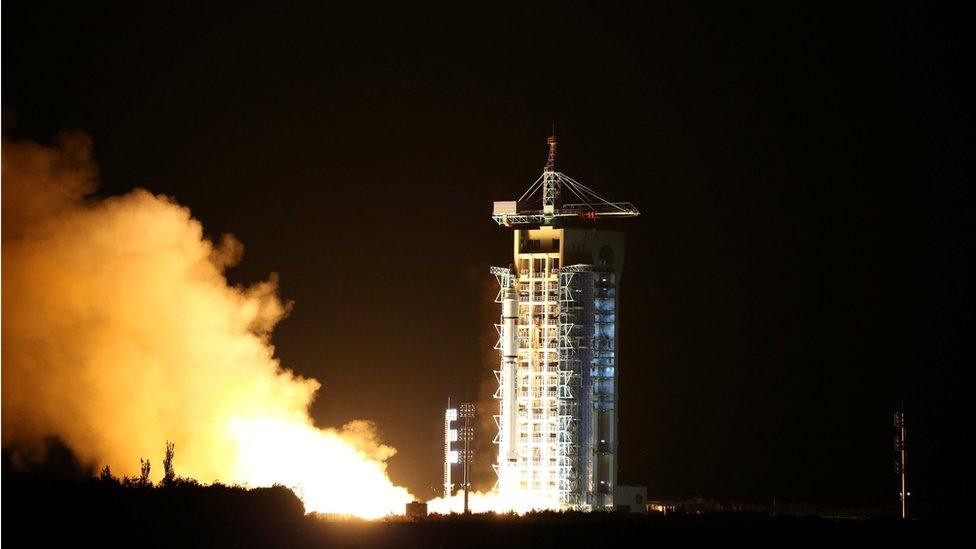

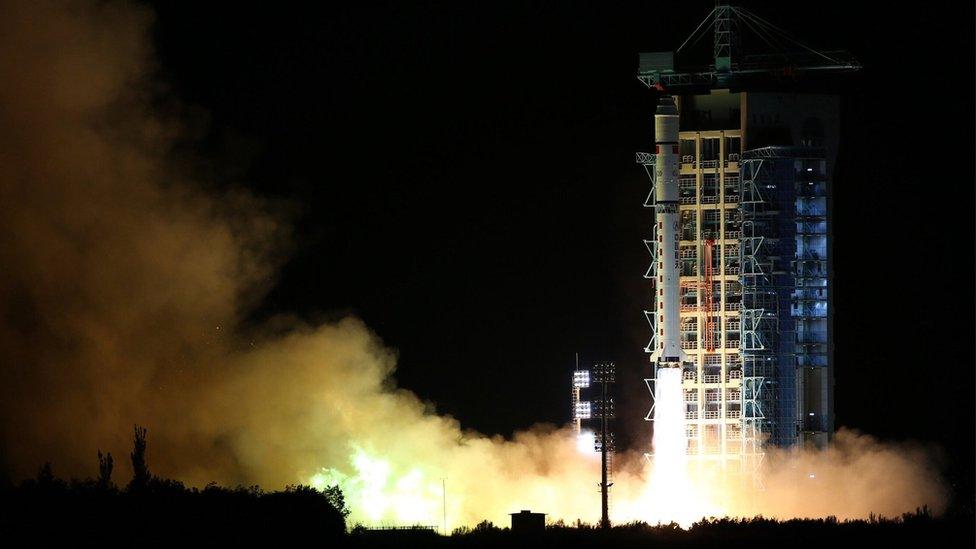

The rocket containing the satellite took off from the Gobi Desert

China has successfully launched the world's first quantum-enabled satellite, state media said.

It was carried on a rocket which blasted off from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre in China's north west early on Tuesday.

The satellite is named after the ancient Chinese scientist and philosopher Micius.

The project tests a technology that could one day offer digital communication that is "hack-proof".

But even if it succeeds, it is a long way off that goal, and there is some mind-bending physics to get past first.

How does it work?

The satellite will create pairs of so-called entangled photons - tiny sub-atomic particles of light whose properties are dependent on each other - beaming one half of each pair down to base stations in China and Austria.

This special kind of laser has several curious properties, one of which is known as "the observer effect" - its quantum state cannot be observed without changing it.

So, if the satellite were to encode an encryption key in that quantum state, any interception would be obvious. It would also change the key, making it useless.

If it works, it will solve the central problem of encrypted communications - how to distribute keys without interception - promising hack-proof communications. The encrypted message itself can be transmitted normally after the key exchange.

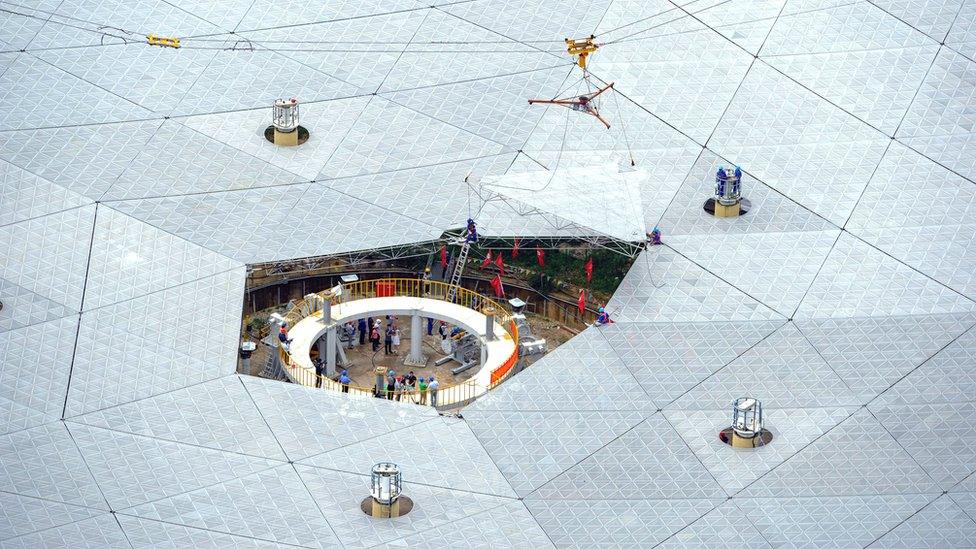

China is spending heavily on both quantum computing research and more secure internet architecture

Has it been done before?

Not from space, making this launch experimental. But fibre-optic quantum key distribution networks already exist in Europe, the US and China.

The signals weaken over distance though, which this project is hoping to minimise by sending the signals mostly through space, keeping attenuation to a minimum despite the distances involved.

But aside from the tricky physics, there is also the difficult matter of firing tiny sub-atomic particles at precise targets on the ground, across vast distances, while travelling incredibly fast through space. There are good reasons this is the first attempt.

Why China?

It has the money. China has allocated vast amounts of money for basic scientific research in its latest five-year development plan. It's also willing to take big risks on some as-yet unproven technologies.

But while China is leading the project, officially titled Quantum Experiments at Space Scale (QUESS), Austria is also involved.

The scientist who first proposed the idea to the European Space Agency (ESA), without success, in 2001, is University of Vienna physicist Anton Zeilinger. He is now working on the latest project under the man whose PhD he once supervised, Pan Jianwei of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The satellite was launched on top of a Long March-2D rocket, from the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Centre in Jiuquan, Gansu Province.

Are other countries also trying this?

Yes, but with smaller, less risky projects. Canada, the US, Japan, the European Space Agency and others are also involved in the field. The UK's University of Strathclyde has also teamed up with the National University of Singapore to do quantum experiments on board tiny satellites. But China's is by far the most ambitious project to date.

If its attempt fails, the others' relative caution may seem sensible. If it succeeds, they will be playing catch-up fast.

What are the applications?

In the face of ever more powerful hacking and surveillance - which could one day also include powerful quantum computers - the security of commercial communications is also increasingly important.

"Quantum computing is largely seen as the next big thing in communications," says Marc Einstein, Director of the Information Communications Technology (ICT) practice of Frost and Sullivan, Japan, citing secure transmission of credit card data as a likely early application.

The broader technology has applications for precision too, he says, in everything from healthcare to industrial production.

"There are millions of applications. Some people say quantum computing could change everything."

- Published4 July 2016

- Published7 August 2016

- Published4 August 2016

- Published19 April 2016