The lonely men of China's 'bachelor village'

- Published

Inside China's "bachelor village": Xiong Jigen shares his story

Xiong Jigen blames the road.

"It's isolated and the transportation is very difficult," he says. Behind him, there is a busy chicken pen and tiers of corn fields outside his home, near the top of a hill.

At 43, Mr Xiong is what is called a "bare branch" in China - single, unmarried, a bachelor.

This is the label given to men like him who have not found a wife, in a country where a man in his twenties is still expected to marry, provide a home and carry on his family line.

He lives in Laoya village in a very rural part of Anhui province of eastern China.

The way to the village is an hour-long slow drive up a dirt road, followed up a walk by a dirt track

The immediate approach to the village is an hour-long slow drive up a dirt road, which turns into a walk up a steep dirt track.

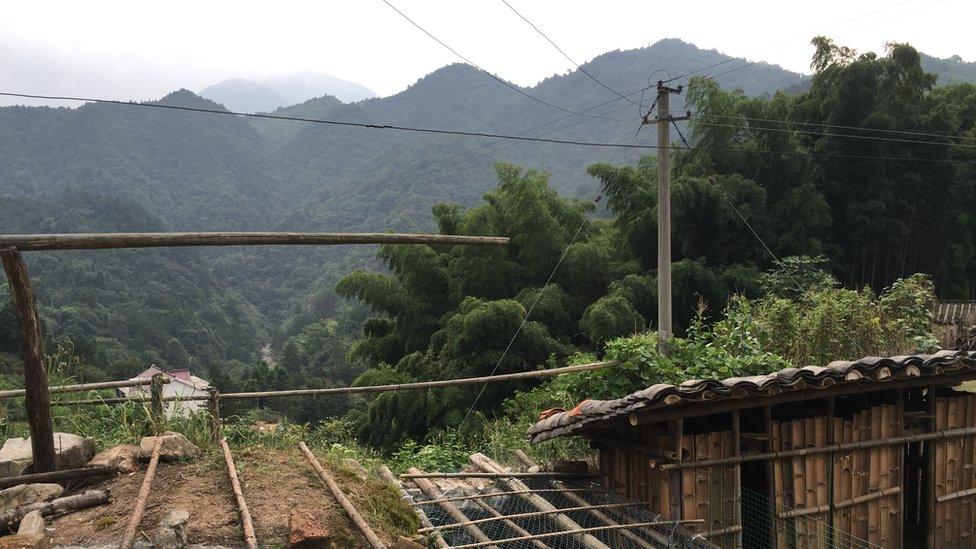

His house is one of seven in a spot surrounded by a forest of bamboo and trees. It is a beautiful scene.

The bachelor village

But Laoya, which means "Old Duck" village, is known locally as the "bachelor village".

In a survey in 2014 it had 112 men between 30 and 55 registered as single out of a population of 1,600. That is unusually high.

Mr Xiong said he knew of more than 100 local men who were still unmarried: "I cannot find a wife, they migrate to somewhere else to work, then how can I find someone to marry?"

Then he mentioned the road again.

"Transportation is so difficult here, we cannot go across the river when it rains. Women don't want to settle down."

The women of the town are known to migrate to other cities, where they often find work, and husbands

His part of the village is remote but the odds are already against Xiong Jigen. China has far more men than women. There are now around 115 boys born for every 100 girls.

In a culture that historically favours boys over girls the Communist Party government's One Child policy led to forced abortions and a glut of newborn boys from the 1980s onwards.

The result is a 21st Century male marriage squeeze.

'Nor too fat, nor too slim'

Parents can still play a significant role in trying to fix up their children. Matchmakers are common in the villages.

Mr Xiong said he had used them: "Some [women] visited here through matchmakers then left, because they had a terrible impression of the transportation."'

As we stood in the doorway of his sparsely decorated bedroom, I asked if he had ever been in love.

Mr Xiong's house, just three years old, is not enough to attract a woman

"I was in a relationship before," he said, "but it didn't work out. She complained that my village was not good for her, especially the roads."

They'd met through a matchmaker. He went on to describe her: "She was almost as tall as me, not too fat nor too slim. She was quite extrovert."

Women leave the village, as they do in other villages all over China, to head to the city for work.

In Anhui where Mr Xiong lives it is Shanghai that is the allure. They find far better pay and for some a husband. Some come back but by then they are, of course, already married.

The men and women who stay

Men migrate too but it is usually just for work. Some men stay to look after their aging parents, in keeping with the Chinese tradition of filial piety.

Xiong Jigen decided to stay to care for his uncle. He was the old man with frayed trousers whom I saw standing outside the house, running his hand through a bowl of bright orange half-dried corn kernels.

His uncle is one of the reasons why Mr Xiong has chosen to stay

"He will not find food if I leave," Mr Xiong said. "He cannot go to the nursing home."

That sense of duty the younger generation has to the elders who brought them up remains a crucial part of family life in China.

President Xi Jinping has spoken about how he believes nothing should get in the way of building a strong, traditional family unit. In Shanghai, new rules came in earlier this year which threaten adult children with punishment if they do not visit their parents.

Some women stay too. Mr Xiong's neighbour Wang Caifeng is still there. At 39, she is a farmer with two daughters and a husband.

"Home town is the best," she told me. "I definitely choose to stay".

39-year-old mum and farmer Wang Caifeng says home is the best place to be

I asked her what the future held for her two girls. They walk for more than an hour, twice a day, to get to school at the moment. Would it be okay if they left the village once they were old enough?

Ms Wang hopes her daughters will stay. But her 14-year-old daughter had a slightly different take on it. Fujing wanted to be a doctor, like her father, but felt this would work best "in the outside world".

The outside world is not that far away. In fact it is in their homes. They have satellite TV, Mr Xiong has a bike. The main street in a small town is not that far away.

For now, it looks like the men of Laoya can only hope- and wait

But Laoya feels thoroughly remote and at times cut off. Even when women have come to see his new house, built just three years ago, it is not enough to persuade them to consider staying to become Mr Xiong's wife.

This is not the only bachelor village. It presents the dilemmas of life in rural China: the relentless escape from poverty and being bound to the land, the gender imbalance, the duty to aging relatives.

And bad roads.

- Published8 April 2016

- Published10 September 2013