How did China save the giant panda?

- Published

The giant panda is a global icon that up until recently was considered to be endangered

They're cute, they're cuddly and they've just been brought back from the brink of extinction.

We're talking about the giant panda, a global icon that's just been taken off the endangered list, largely due to Chinese conservation efforts. But how exactly did they do it?

It's all about the bamboo

China has been trying for years to increase the population of the giant panda.

Bamboo makes up for 99% of a panda's diet

The bears, China's national icon, were once widespread throughout southern and eastern China but, due to expanding human populations and development, are now limited to areas that still contain bamboo forests.

The success is due to Chinese efforts to recreate and repopulate bamboo forests.

Bamboo makes up some 99% of their diet, without which they are likely to starve.

Pandas must eat 12kg (26 lbs) to 38kg worth of bamboo each day to maintain their energy needs.

There are now an estimated total of 2,060 pandas, of which 1,864 are adults - a number which has seen their status changed from "endangered" to "vulnerable", on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)'s Red List.

"It's all about restoring the habitats," Craig Hilton-Taylor, Head of the IUCN Red List, told the BBC.

"Just by restoring the panda's habitat, that's given them back their space and made food available to them."

A loss of habitats was what caused the number of pandas to drop to just over 1,200 in the 1980s, according to Mr Hilton-Taylor.

"You need to get the bamboo back and slowly the numbers will start to creep back," he said.

There are now an estimated total of 2,060 pandas

Ginette Hemley, senior vice-president for wildlife conservation at the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) agreed.

"The Chinese have done a great job in investing in panda habitats, expanding and setting up new reserves," said Ms Hemley. "They are a wonderful example of what can happen when a government is committed to conservation."

Yet this success could be short-lived.

Climate change is predicted to wipe out more than one-third of the panda's bamboo habitat in the next 80 years.

Pandas must eat up to 38kg worth of bamboo each day to maintain their energy needs

"With the change in climate, it's going to get too hot for the bamboo to grow," Mr Hilton-Taylor explained.

"Giant pandas are very dependent on bamboo for food and with a loss in bamboo, it's not looking very promising for them."

So is captive breeding the answer?

Many zoos and Chinese facilities have placed their bets on breeding giant pandas in captivity, sometimes using artificial insemination methods.

Baby giant panda twins were on Sunday born in an Atlanta zoo - their mother had been artificially inseminated.

Many scientific facilities now use artificial insemination methods to breed pandas

But many of these pandas are used to a life in captivity, and are unable to return back into the wild

"Having captive animals is like an insurance policy," said Mr Hilton-Taylor. "But you don't want to keep them in captivity forever."

The eventual goal of most captive-breeding programmes is to let the animals back into the wild eventually.

"There have been a couple of attempts to introduce pandas into the wild, but they haven't been successful," said Ms Hemley. "We're not out of the woods yet."

In 2007, the first captive-born giant panda ever released into the wild, Xiang Xiang, died after being beaten up by wild panda males.

But why has the panda got everyone so obsessed?

The Tibetan antelope is another animal that has also been delisted on the IUCN's red list, yet more focus has been placed on the panda, which has come to be seen as an icon for animal protection efforts.

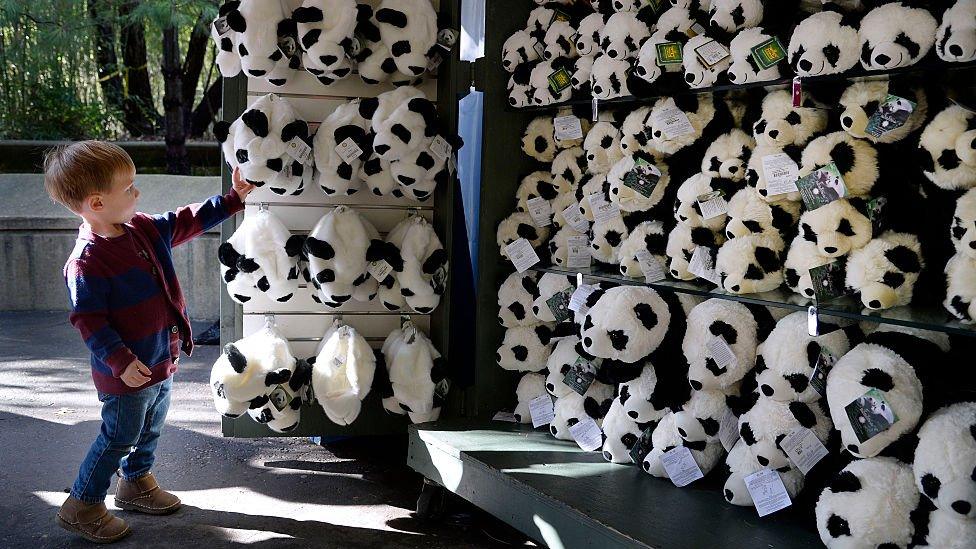

It's not uncommon to see children clutching giant panda soft toys

But what is it about the panda that's got us all cooing in unison?

"Their black and white markings and big black eye patches make them very charismatic. There's nothing like them in the world," Ms Hemley explained.

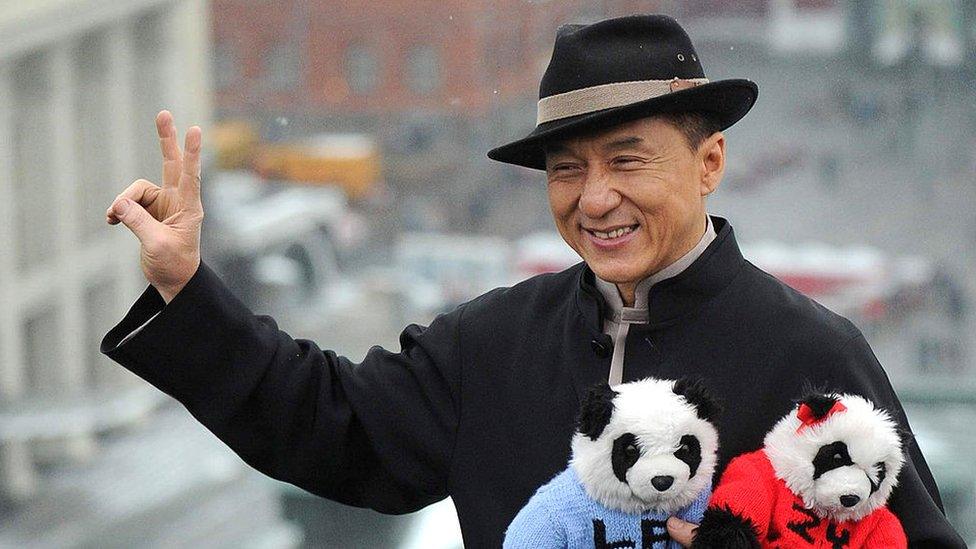

Even film star Jackie Chan's got a bad case of pandamonium

"A happy coincidence of their natural adaptations result in what humans perceive as cute, and a cute and cuddly face is a whole lot easier to love," said Dr Cheng Wen-Haur, Chief Life Sciences Officer and Deputy CEO of the Wildlife Reserves Singapore.

"In the words of Baba Dioum, in the end we will only conserve what we love."

- Published4 September 2016

- Published4 September 2016

- Published27 June 2016

- Published8 August 2016