China blocks Hong Kong lawmakers in a reminder of who is in charge

- Published

Beijing has told Hong Kong it cannot use the legislature to campaign for ideas offensive to China

"I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it" is an 18th Century trumpet call for free speech, one often repeated by parliamentarians around the world… but never in China.

The message from Beijing to its unruly territory 2,000km (1,350 miles) south is, by contrast, "we disapprove of what you say and we hereby decree that you have no right to say it".

China has now spoken on the question of whether elected members of Hong Kong's legislature can use that public platform to campaign for ideas offensive to China and the answer is a resounding no. In a unanimous decision by a panel of the Communist Party-controlled national parliament, Hong Kong has been reminded that the freedoms it enjoys are ultimately at the whim of Beijing.

Today's "interpretation" of Hong Kong's mini-constitution is one of the most significant interventions in Hong Kong's legal system in two decades of Chinese rule. It is the first time China's parliament, without the request of either the Hong Kong government or Court of Final Appeal, has interpreted the mini-constitution at a time when the issue is under active consideration in a Hong Kong court.

Why didn't China's politicians wait till after a court ruling on whether two legislators might be allowed to retake their oaths? Li Fei, the chairman of the Basic Law Committee of China's parliament, made the logic clear when he said the Chinese government "is determined to firmly confront the pro-independence forces without any ambiguity".

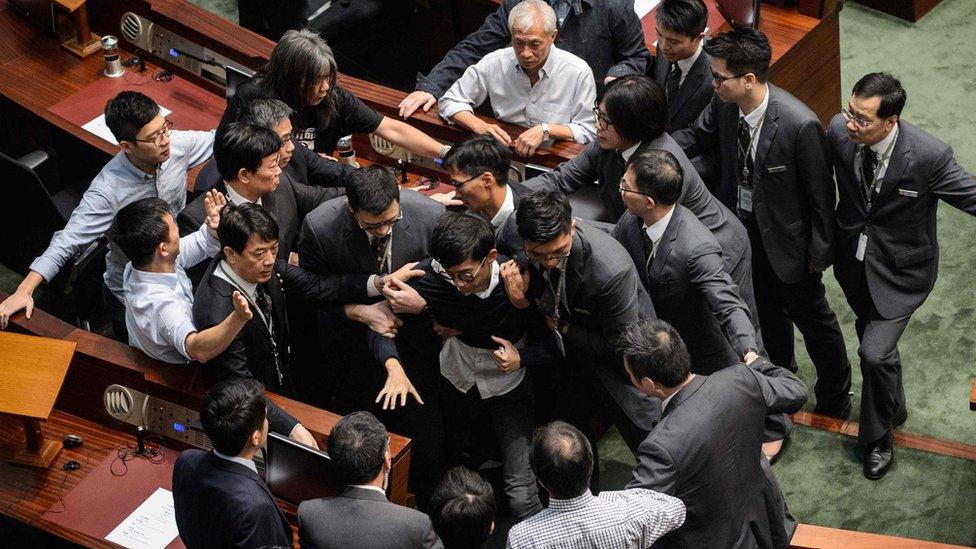

Yau Wai-Ching had used her oath-taking attempts to insult China

The interpretation is a highly confrontational move which plunges Hong Kong into a new phase of its long running political and constitutional crisis. But Beijing's move comes in response to an equally confrontational move from the other side.

The two lawmakers, Sixtus Leung and Yau Wai-ching, who used their swearing-in ceremony to insult China and talk of a "Hong Kong nation" should have known that a Chinese government so sensitive to questions of national pride and dignity would feel it had no choice but to act.

It was no surprise when China's parliament said their words and actions had "posed a grave threat to national sovereignty and security", with Li Fei adding: "The central government's attitude is absolute. There will be no leniency."

A price worth paying

The scope of Monday's interpretation will raise inevitable questions about whether China is interpreting Hong Kong law, which is allowed, or re-writing it, which is not. And apart from disqualifying the two young legislators at the heart of the crisis, it will raise a raft of questions about the way in which some of the other newly elected young democracy activists took their oaths.

For example, does reciting the oath in slow motion or using eccentric intonation contravene the interpretation's insistence on "genuine" sincerity and solemnity? Who will decide? And if Beijing doesn't like the decision of a Hong Kong court, what will it do next? For that matter, where does Beijing's intervention leave the ongoing review of the oath taking question in Hong Kong's courts?

Ms Yau (left) and Sixtus Leung (right) have refused to pledge allegiance to Beijing

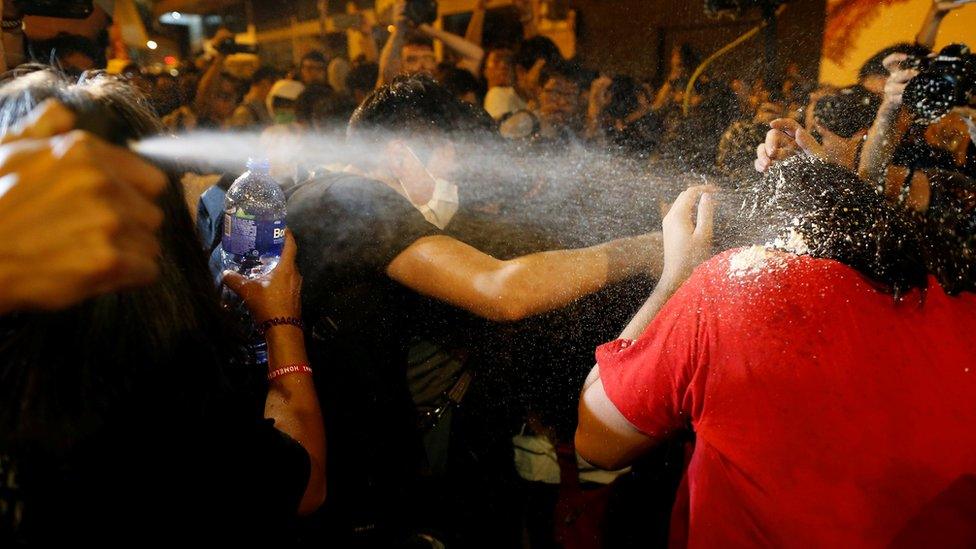

The Hong Kong Bar Association warned in advance that an interpretation of the Basic Law by the Chinese parliament at this moment would be a severe blow to the territory's judicial independence. On Tuesday it plans a silent protest, yet another worry for police after Sunday's tense standoff with thousands of protesters outside a Chinese government office in Hong Kong.

But for Beijing, all these problems are small ones. Its bottom line is that a handful of perceived troublemakers in a city of 7m people cannot be allowed to trump the needs of a Chinese nation of 1.3bn. A row over judicial independence, a constitutional crisis even, is a price China's leaders are prepared to pay to get the independence genie back in the bottle.

Beijing sees any talk of independence as threatening Chinese sovereignty. Separatism is a crime and in Tibet or Xinjiang, campaigning for independence results in a lengthy jail term.

When the leader of Taiwan's China friendly opposition party Hung Hsiu-chu visited Beijing last week, Taiwanese press reported Chinese President Xi Jinping as telling her that the Chinese Communist Party "would be overthrown by the people if it failed to properly deal with Taiwanese pro-independence".

Fuelling the fire?

Mr Xi knows that his credibility and that of the party will suffer if "the people" see an independence movement take hold among Chinese citizens in Hong Kong.

In this context, to allow elected members of Hong Kong's legislature to use the public platform of the Legislative Council to insult China and talk of a Hong Kong nation is unthinkable.

Two worldviews collide here. One in which Chinese identity trumps all others and where Mr Xi's "great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation" requires all compatriots to unite under one flag.

The democracy activists could now capitalise on anger in Hong Kong

The other worldview, shared by many young people in Hong Kong and Taiwan, is that democratic freedoms trump all else, including Chinese citizenship. If they can't have meaningful democracy under Chinese rule, then this constituency conclude that perhaps they should do without Chinese rule. These worldviews are simply not compatible.

Worse, every time Beijing uses the stick rather than the carrot to bring Hong Kong to heel, it alienates young voters further. Until this year hardly anyone in Hong Kong talked of self-determination or independence, but now such ideas are gaining currency.

As Beijing's interpretation of the law disqualifies their elected representatives, the question for Hong Kong's young democracy activists is whether they can capitalise on popular indignation, and where to take their defiance next.

- Published2 November 2016

- Published6 November 2016

- Published12 October 2016