China and the Church: The 'outlaw' do-it-yourself bishop

- Published

Dong Guanhua is one of many religious leaders unrecognised by Church or state

Dong Guanhua is a thorn in the side of both the Vatican and the Chinese state. Without the Pope's permission, or Beijing's, this 58-year-old labourer from a village in northern China calls himself a bishop.

China and the Vatican are believed to be close to a historic agreement governing the selection of bishops for 10 million Chinese Roman Catholics.

Such an agreement would be the first sign of rapprochement between a mighty state and a proud Church since the Communist Revolution of 1949.

Father Dong Guanhua has been kicked out of the Chinese Catholic church for calling himself a bishop

The last thing either side wants at this delicate moment is a do-it-yourself bishop like Dong Guanhua getting in the way.

There are about 100 Catholic bishops in China. It's a muddled and troubled picture with some approved by Beijing, some approved by the Vatican and, informally, many now approved by both.

Outlaw

After seven decades of conflict, both Church and state would like to bring order to this fractured patchwork. But China's Roman Catholics are not privy to the details of the deal under negotiation and Dong Guanhua fears it will only make divisions worse.

"I respect the Pope but I don't support this. The Church will be harmed because this hardline government will not bend. It actually wants to create chaos in the true Church. The more chaos the better in the government's mind."

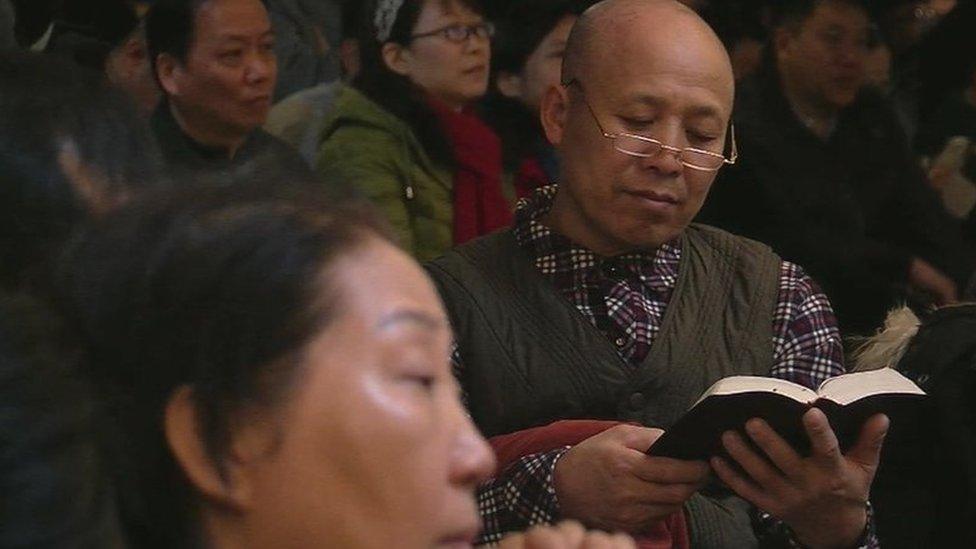

Christianity, like most religions, has long been repressed in China

Dong Guanhua has long been an outlaw in Beijing's eyes. The lifelong Catholic from Zhengding County in Hebei Province has refused to register with the state's Patriotic Catholic Association, because it does not acknowledge the authority of the Pope and, in turn, is not recognised by the Vatican.

Instead he cleaves to the so-called "underground church" - the community which recognises only the spiritual legitimacy of Rome.

But as the Vatican draws closer to Beijing, it too has now denounced Dong Guanhua's decision to call himself a bishop as a "grave crime". In other words, Dong Guanhua has become an outlaw twice over.

He says he'll answer to his conscience and shrugs off critics from both powerful camps who say his behaviour is crazy.

"There are people who say Jesus was crazy too. Sometimes the government gives rewards to people who yield. I don't covet those rewards. I'm not afraid of anything because my conscience is clear."

The pews are quiet in the government-sanctioned church near Father Dong's unofficial one

Dong Guanhua has no church. Instead he preaches at home, with farming families in quilted jackets huddled in his front yard. Under an open sky they chant the responses of the Mass, a pale sun filtering through toxic haze and tangled power lines to illuminate their faces.

Despite the freezing temperatures and the fear of police harassment, there are far more worshippers here than in the big local government church across the road: Dong Guanhua's congregation unwilling to let the state get between themselves and their God.

"If there was religious freedom, we would go to the state church. We don't want to be out in the cold," he says.

"Above ground" churches have accepted state supervision

Above ground

Some 200 miles (320km) away, a very different Sunday service in being held.

Beijing's magnificent South Cathedral is not a church for outlaws but part of the state-approved Catholic faith. There every pew and every aisle is full, old and young gazing through clouds of incense towards a statue of Christ flanked by vases of green bamboo stems.

Generation to generation, these "above-ground" Catholics too have held onto their faith, while accepting state supervision.

Asked how they feel about the prospect of an agreement between their government and the Pope, many are unwilling to comment.

But some are cautiously optimistic and one woman declares defiantly that if the Church in China could be led by the Pope without government involvement, it would "make the faith more pure".

Pope Francis clearly yearns for the opportunity to heal this long-divided Church and to be recognised as spiritual shepherd of the above-ground flock as well as the underground flock.

An agreement with Beijing which allowed this, and which achieved a compromise on the selection of bishops, would also be a first step to re-establishing diplomatic relations between the Vatican and China.

Many worshippers at Beijing's Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception (South Cathedral) were reluctant to comment

For Beijing, the prize is also great. Agreement with the Vatican might help impose order on a troublesome and conflicted community, leaving outlaws like Dong Guanhua marginalised.

Globally, it would also enhance China's prestige. At last, the world's rising superpower engaging with the world's super soft power.

Treading carefully

Many are hopeful. Father Jeroom Heyndrickx is a Belgian priest who has spent 60 years trying to help China's Catholics and says that despite doubters and obstacles on both sides, this is the best opportunity in his lifetime.

"For 2000 years in China, the emperor was emperor and pope at the same time and this also applied to communist China. But China has changed and the Church has changed and this is what constitutes a new opportunity for this dialogue to succeed.

"China knows that globalisation is happening. Now it openly professes itself to be a country ready to have a dialogue with all different kinds of ideology."

Pope Francis is doing his utmost to make dialogue succeed. He has been careful to avoid criticising China on religious freedoms or human rights.

He has met groups from the state-backed Chinese church on their visits to Rome.

It is unclear what an agreement would mean for underground or over ground churches

As a result, some underground Catholics complain that he risks betraying the memory of those who suffered and died for their loyalty to Rome, and abandoning today's true believers to the control of a communist state.

They also point to tightening control in many areas of Chinese public life and worry that a deal between Beijing and the Vatican may result in less religious freedom not more.

'No compromise'

One leading sceptic is Joseph Zen, the retired cardinal of Hong Kong.

In a recent interview he told the BBC: "A bad agreement makes the situation worse. Without an agreement, we have to tolerate many things but that's OK. Our faith tells us that we have to suffer from persecution. The communist regime never changes its policies. They don't need to compromise. They want a complete surrender."

China's religious authorities declined all requests for interview.

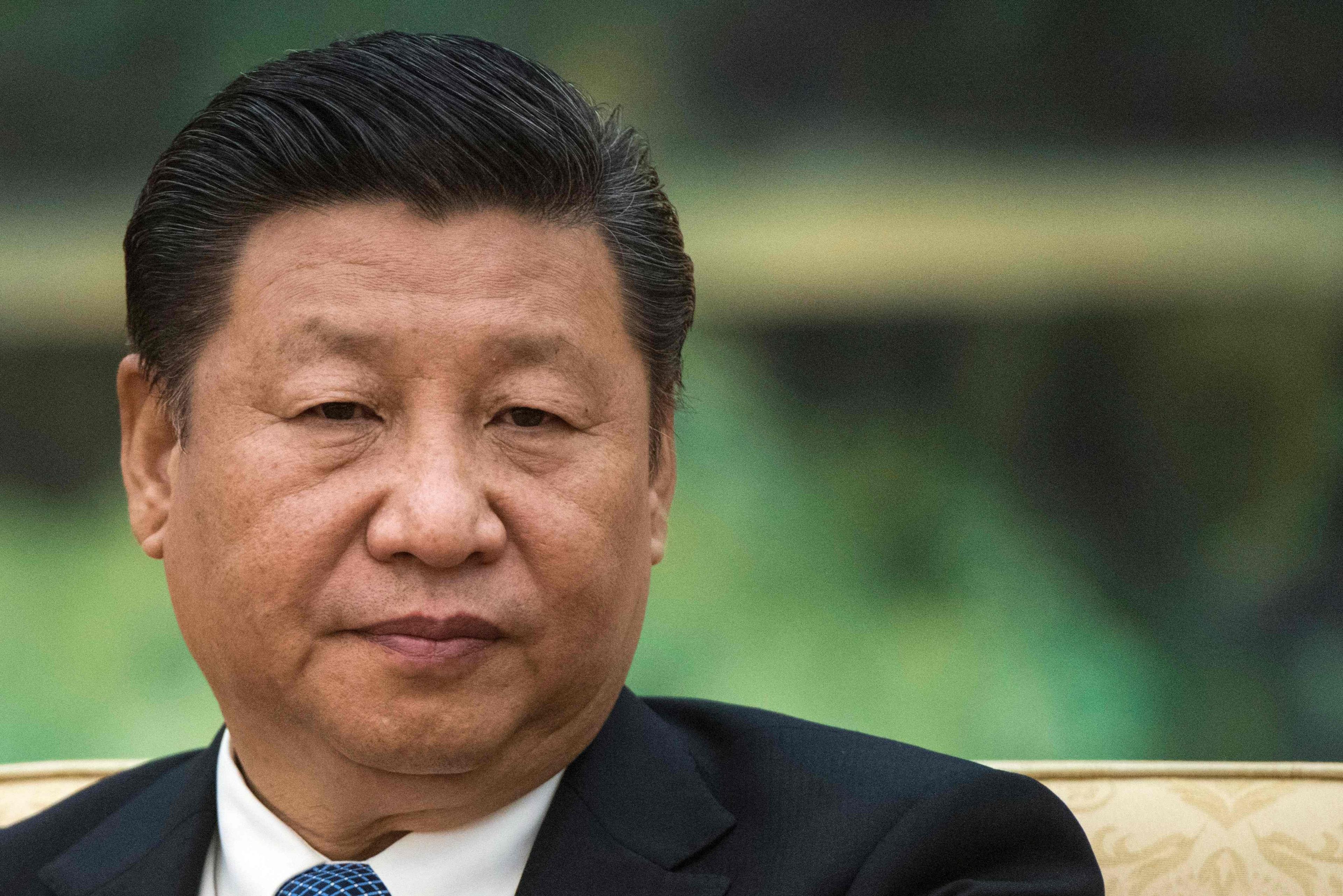

President Xi Jinping has centralised power in himself and cracked down on rival ideologies

Back in the yard of the outlaw bishop, with the open-air service over and the congregation departed, Dong Guanhua draws a red curtain around his altar to protect it from the elements.

The last dry leaves whisper from winter branches and a couple of chickens look on from a corrugated iron roof.

Asked what message he has for Pope Francis on the threshold of a historic agreement, he replies: "I would tell him to be careful. If the deal goes well, God will be pleased, but if it doesn't, the Pope will be punished. Compromise is a bad thing. It breaks the integrity of our faith. Ninety percent of believers here share my opinion."

The first flakes of winter snow swirl down and Dong Guanhua goes inside to pray. The yard is empty and night is falling fast.

The silence seems to hold a thought - that deals between a mighty faith and a mighty state are only one recurring theme in Christian history, and that individual conscience is another.

- Published2 December 2016

- Published26 March 2016

- Published5 February 2016

- Published1 February 2016

- Published22 November 2016

- Published10 November 2016