Wu Yongning: Who is to blame for a daredevil's death?

- Published

Mr Wu made his name as a "rooftopper" dangling from skyscrapers, as seen in pictures from previous climbs

Last month, Wu Yongning went out to do what he loved best - scale a skyscraper without safety equipment and film himself dangling off its roof by his fingertips.

What happened next almost seems inevitable - the Chinese climber fell, plunging 62 storeys to his death.

His many thousands of followers grew concerned when he stopped posting videos of his stunts on sites like Huoshan and Kuaishou, but his death was only confirmed in recent days, first by his girlfriend, then by authorities.

A shocking clip of what appeared to be his final moments - his fatal attempt to scale a building in Changsha city - began circulating online this week.

His death has prompted uneasy soul-searching over the "cash for clips" internet video industry. Questions are now being asked about whether these platforms, and their viewers, are in some way responsible for his death.

A recent Beijing News investigation found that Mr Wu had posted more than 500 short videos and livestreams on Huoshan, garnering a million fans and earning at least 550,000 yuan (£62,000; $83,000). Huoshan had prominently promoted his videos as recently as June.

Huoshan's slogan on its website reads "Take a video, you can earn money"

The reports prompted stern commentaries in national media.

"These livestreamers make 'close to death' reality clips, while the platforms profit as the middlemen... [We] cannot let these platforms become ruthless, cruel battlefield-like places," read one op-ed piece by news outlet The Paper.

State broadcaster CCTV said in a commentary that such sites "should not, in their quest for profit, selectively ignore the fact videos can bring about harmful social consequences".

Huoshan has since strenuously denied it encouraged Mr Wu's stunts, saying in a statement that while it "always respected extreme sports athletes' spirit of exploration and their works", it was also "always cautious, we do not encourage nor have we ever signed agreements" with them.

It is suing Sina News, one of China's biggest news outlets, after it reported claims from Mr Wu's relatives that it had financially backed the deadly climb.

Kuaishou also denied it collaborated with Mr Wu. A recent BBC check found Mr Wu's clips had been scrubbed from the two platforms.

'Crowdfunding his death'

But while no-one ever forced him to scale a building, some have asked whether Mr Wu's viewers also carry some responsibility for his death.

The debate over viewers' complicity has intensified as more people around the world practise "rooftopping" and share their clips on social media - the craze swept Russia earlier this year and has already claimed several lives.

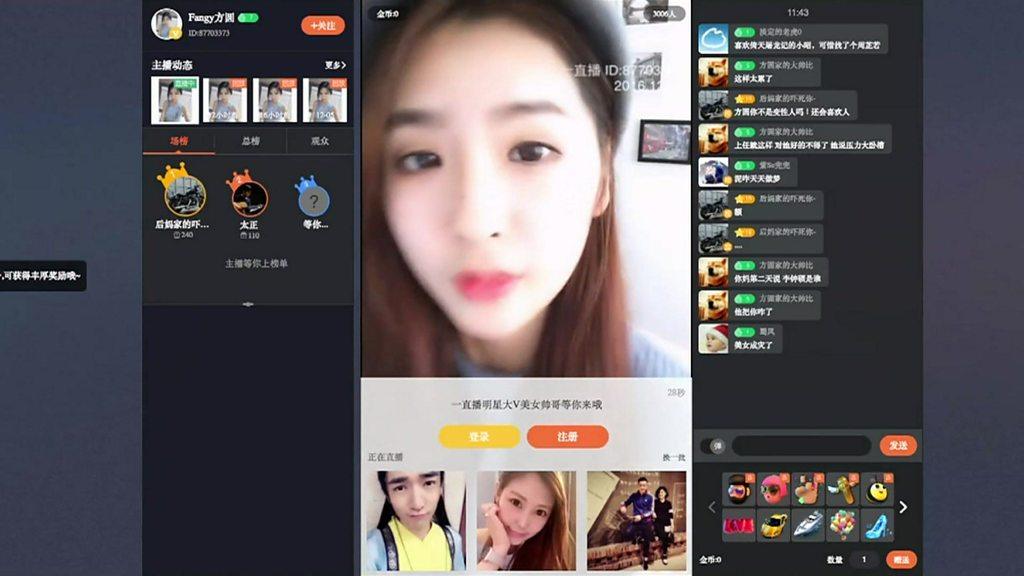

But the question is particularly pointed in China, because livestreamers and viral video-makers can earn money from fans directly. Many Chinese video platforms allow followers to send virtual gifts, which can then be converted to cash.

The Paper's op-ed accused viewers of clips like Mr Wu's of "purchasing a life", while one commenter on discussion site Zhihu said: "Every single person who 'liked' (Mr Wu) basically took part in crowdfunding his death."

"Watching him and praising him was akin to... buying a knife for someone who wanted to stab himself, or encouraging someone who wants to jump off a building," said a user on microblogging network Weibo.

"Don't click 'like', don't click 'follow'. This is the least we can do to try to save someone's life."

Wild West

The conversation comes as China struggles to contain the fast-evolving, billion-dollar internet video industry. Millions are broadcasting their lives on livestreams, and nearly half of China's 710 million internet users are watching them.

The 'online goddess' who earns $450k a year

China may be infamous for its censorship and internet restrictions, but the world of livestreams and short videos remain a Wild West of sorts.

Fierce competition for eyeballs has led to attention-grabbing antics, from eating live goldfish and chugging down raw eggs, to stripteases and "rooftopping".

Some platforms have actively encouraged this - earlier this year, Huoshan announced it was dishing out 1 billion yuan to broadcasters who made viral content., external

In an attempt to tamp down on the industry's exuberance, the government last year set out rules for livestreaming such as a ban on "obscene material" - including "erotic banana-eating" - and compelled platforms to step up control and monitoring of their content.

China shuts down thousands of live stream accounts

Mr Wu's death has reignited discussions on whether more needs to be done, such as greater regulation. The People's Daily newspaper - mouthpiece of the ruling Communist Party - said in a Weibo commentary that "bloody livestreams should be controlled".

"These kind of eyeball-grabbing livestreams should be cancelled," said one Weibo user, while another said: "Anything that parents wouldn't allow to be broadcast should be scrubbed."

But a few have pushed back, saying calls for censorship were a knee-jerk reaction.

"My goodness, looking for yet another excuse to regulate video platforms?" questioned one Weibo commenter.

"When you can't control something you just want to throw it out, and when ideas can't catch up, you just end up blaming livestreams."

Additional reporting by Wei Zhou

- Published11 December 2017

- Published18 August 2017

- Published6 December 2017

- Published18 August 2017

- Published19 August 2016

- Published7 December 2016