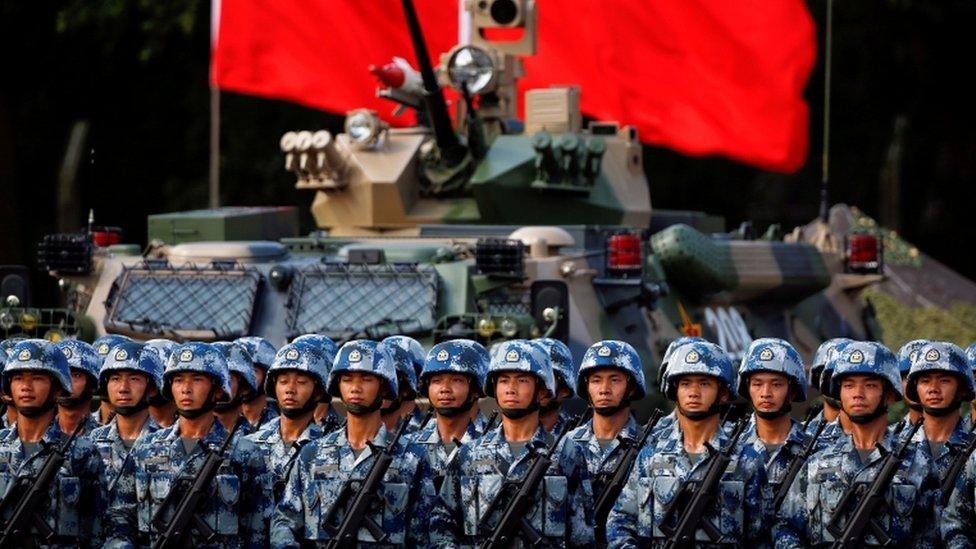

The 'globalisation' of China's military power

- Published

Experts say China is developing weaponry tailored for export to specific markets, including some deemed too sensitive for Western manufacturers

China's modernisation of its armed forces is proceeding faster than many analysts expected.

Now, according to experts at the International Institute for Strategic Studies - the IISS - in London, it is China and no longer Russia, that increasingly provides the benchmark against which Washington judges the capability requirements for its own armed forces.

This is especially true in terms of air and naval forces - the focus of China's modernisation effort. Events in Europe mean that for the US Army, it is still largely Russian capabilities that provide the benchmark threat.

This trend has been chronicled in the Military Balance, the annual assessment of global military capabilities and defence spending, published by the IISS since 1959.

Of course the transformation of the Chinese military has been under way for some time. But now a significant way-point has been reached - or is very close - that will make it the "peer competitor" for Washington.

Ahead of the publication of this year's Military Balance later this week, I sat down with a group of IISS experts to try to tease out more of the details of this trend, providing a powerful narrative to the annual compendium's tables and statistics.

China's progress and technical abilities are remarkable - from ultra-long-range conventional ballistic missiles to fifth generation fighter jets. Last year the first hull of China's latest warship - the Type 55 cruiser - was put into the water. Its capabilities would give any Nato navy pause for thought.

China is working on its second aircraft carrier. It is revamping its military command structure to give genuine joint headquarters involving all the key services. In terms of artillery, air defence and land attack it has weapons that out-range anything the US can deploy.

Since the late 1990s, when it received an influx of advanced Russian technology, the Chinese Navy has recapitalised the bulk of its surface and sub-surface fleets.

China's first domestically built aircraft carrier was launched in April 2017

In the air, its new single-seat fighter, the J-20, is said by the Chinese to be in operational service.

It is what is known in the trade as a "fifth generation fighter", meaning that it incorporates stealth technology; it has a supersonic cruising speed; and highly integrated avionics.

IISS experts remain sceptical.

"The Chinese Air Force", they say, "still needs to develop suitable tactics to operate the low-observable jet and must come up with doctrines to mix these 'fifth generation' warplanes with earlier 'fourth generation models'.

"Still, China's progress is clear," they say, "you can add to these aircraft a whole range of capable air-to-air missiles that are every bit on a par with those in Western arsenals."

This year's Military Balance devotes a whole chapter to developments in Chinese and Russian air-launched weapons which they see as a key test for western dominance.

The US and its allies have waged air campaigns since the end of the Cold War and have lost very few aircraft. But this dominance, according to the IISS, may be increasingly challenged. China, for example, is developing a very long-range air-to-air missile intended specifically to strike at tanker and command and control aircraft that now orbit out of harm's way; essential but vulnerable elements in any air operation.

The authors of the Military Balance argue China's air-to-air missile developments by 2020, "will likely force the US and its regional allies to re-examine not only their tactics, techniques and procedures, but also the direction of their own combat-aerospace development programmes".

On land the Chinese army is lagging behind in this modernisation effort according to the IISS. Only about half of its equipment is serviceable in terms of modern combat.

But even here progress is being made. China has set a goal of 2020 as the date to achieve both "mechanisation" and what it calls "informisation". Quite what China means by this is latter term is unclear, but Beijing has been watching the developing role of information in warfare and seeking to adapt this to its own particular circumstances.

An armed Chinese drone of the type for sale to other countries

China has one clear strategic aim in mind to which many of its new weapons systems are tailored. In the event of a conflict, this is to push US military power as far away from its shores as possible, ideally deep into the Pacific. This strategy is known in military jargon as "anti-access area denial" - sometimes abbreviated as A2AD. This explains China's focus on long-range air and maritime systems that can hold the US Navy's carrier battle groups at risk.

So as a military player China has pretty well joined the Premier League. But this though is not the end of Beijing's global military impact. It is also pursuing an ambitious arms export strategy. Often China is willing to sell advanced technologies that other countries either do not have, or are unwilling to sell to all but their closest allies.

The market for armed drones is a case in point. This is a rapidly spreading technology that raises huge questions about the boundary between peace and war. The US, which was one of the pioneers in this field, has refused to sell sophisticated armed drones to anyone except a limited number of its closest Nato allies like the United Kingdom. France, which already operates US-supplied Reaper drones, has plans to arm drones as well.

China has had no such constraints, displaying impressive unmanned aerial vehicles alongside the various munitions that they can carry at arms shows around the world. The IISS Military Balance says that China has sold its armed UAVs to a number of countries including Egypt, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Myanmar, among others.

This is a very good example of unintended consequences. Washington's reluctance to sell this technology leaves the field open to Beijing. Inevitably this has a wider role in the spread of such weapons, encouraging other countries who operate UAVs solely for intelligence gathering purposes to seek armed variants as well.

US and Western arms exporters see China as a growing commercial threat. Compared with even a decade ago, there is a serious Chinese presence in the marketplace, offering good quality equipment. China, as the armed UAV example illustrates, is also willing to enter markets which many Western manufacturers, or their governments, see as being too sensitive.

And as the IISS experts told me, China tends to win on all aspects of the deal. Typically Chinese weaponry will give you 75% of the capability of the available Western technology for 50% of the price. In business terms it's a strong offer.

The Thai army testing out a newly purchased Chinese-manufactured VT4 main battle tank in January 2018

China's ground warfare exports are less impressive. They still have to compete for customers with countries like Russia and Ukraine. But when Kiev couldn't meet the timeframe for a tank deal with Thailand in 2014, the Thais bought Chinese VT4 tanks instead. Last year Thailand went back for more.

IISS experts say that China is also trying to develop weaponry tailored to specific markets. They point to a new light tank for example intended for African countries, whose roads and infrastructure would not be able to cope with many of the heavier models offered by others.

China's growing role as a source of sophisticated weaponry is something that is worrying many countries and not just its neighbours. Western air forces have enjoyed some three decades of dominance. But the "anti-access" strategy of the Chinese has provided weapons that could easily be employed by others to do the same thing.

A Western European country may never face China in a conflict, but it could well face sophisticated Chinese weapons systems in the hands of others. As one IISS expert put it, "the perception that you will enter a low-risk environment when intervening overseas, now needs to be questioned."

- Published28 November 2017

- Published9 October 2017

- Published24 August 2017

- Published28 November 2017

- Published4 March 2015

- Published18 January 2012