China #MeToo: Why one woman is being sued by the TV star she accused

- Published

The #MeToo phenomenon is slowly but surely taking off in China - but it isn't without its struggles

Just a few months ago, China was hit by a string of #MeToo accusations that emerged from arenas as diverse as temples, universities and television talk shows. Now, one case is set to go before China's civil courts but it is the accuser, not the accused, who is having to defend herself.

In July, China's entertainment world was faced with the allegation that one of the country's biggest and most beloved TV stars had forcibly groped and kissed an intern after she took a basket of fruit to his room.

Zhu Jun, known for hosting national television extravaganzas such as the Spring Festival Gala, immediately denied the accusation and proceeded to sue her for damaging his reputation and mental wellbeing.

The woman, known by her online moniker Xianzi, was finally told on Tuesday that the case will be heard in Beijing's Haidian district court.

She has now filed a countersuit and intends to fight the case, thus setting up China's first #MeToo confrontation in court.

Desperation and denial

The case is a telling insight into how China is negotiating the #MeToo phenomenon that has swept the world and seen dozens of high-profile figures being publicly shamed for alleged sexual misconduct.

When 25-year-old Xianzi posted her 3,000-word account on WeChat, she wasn't expecting a huge amount of attention. But when her friend Xu Chao re-posted it on China's biggest social media site Sina Weibo - it immediately began to go viral.

Xu Chao is now also being sued by Zhu Jun - who also demands compensation and a public apology from her, arguing that the situation has caused him great distress.

Zhu Jun is a prominent TV star in China

The alleged incident is said to have taken place four years ago, but in her account Xianzi alleges that the police told her to drop the accusation because Mr Zhu was a prominent TV host and his "positive impact" on society should make her think twice.

She also alleges that the authorities went as far as contacting her parents and said she should keep quiet for their sake.

Soon after she came forward, Xianzi claimed to have received several threatening phone calls: "Believe it or not, I'll get to your Mum," a deep male voice said in a voice recording she posted later on Weibo.

With no other witnesses or allegations against Zhu Jun forthcoming, the case looks to be a simple case of his word against hers. But for both women this is about making a point on a public stage in China, where #MeToo has failed to make significant progress as a movement.

Xianzi told the BBC she would not change her stance: "I don't want society to expect the perfect victim who never makes any mistakes and asks [for] no compensation.

"Many people ask #MeToo victims why you don't make a report to the police immediately. I'm the one who did report to the police four years ago and I didn't receive any justice. Still there are people who instruct female victims to do this... but not men. I want to correct this by standing up."

Xu Chao had this to say: "What deeply concerns the victims is whether this injury leads to justice or nothing."

She is pessimistic about China's ability to allow #MeToo to become a fully-fledged part of the mainstream conversation, the way it has elsewhere.

"China is a bit different. There is a gap between public opinion and legislation," she says, but adds: "I won't give up."

The #MeToo movement is part of the mainstream conversation in many parts of the world, including South Korea, but Xu Chao says it is different in China

Mr Zhu's lawyers have consistently denied the allegations set out against him and did not respond to requests for comment from the BBC. The lawsuit demands both women apologise online and in a national newspaper and pay compensation.

It's clear that there is a high degree of sensitivity in Chinese official circles about the extent to which they should encourage or even simply tolerate #MeToo discussions. Coupled with the social and cultural pressures for women to toe the line, it means the movement has struggled here like nowhere else.

And then there's the unavoidable issue of censorship. If Chinese authorities aren't happy about what's being presented online, they can simply choose to get rid of it - as they have done in the past.

"We observed [about] a dozen Chinese women who came forward on Weibo with accusations of sexual assault," said Prof Fu King-wa, who runs Weiboscope, a censorship tracker, out of Hong Kong University's Journalism and Media Studies Centre.

"In many cases, there was an apparent link between online censorship and strong public reaction to [these] #MeToo incidents. China's censor is more likely to intervene when a personal accusation [is met with] a large scale of online reaction... and when the posts potentially [pose] higher threats to the country's political, social or moral order."

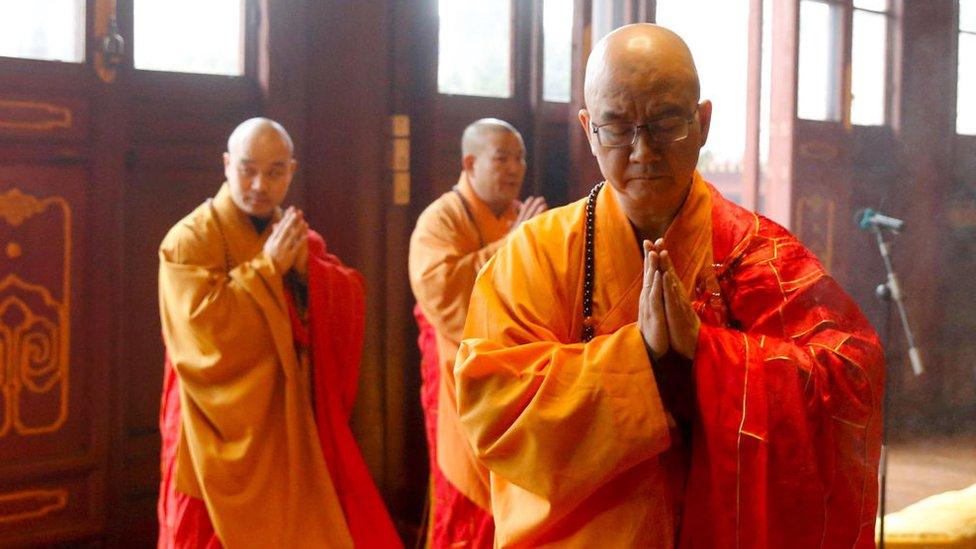

But there have been cases to buck a pessimistic outlook. Another accusation that emerged this summer pointed the finger at the abbot of China's powerful Longquan temple, who was also a political adviser to the government and the youngest person ever to hold the position of head of the Buddhist Association of China. He was to become one of China's most high profile #MeToo casualties.

An extraordinary 95-page report written by two monks accused him of sending illicit messages attempting to control the minds of nuns by claiming sex was part of their study of Buddhist doctrines.

Almost as soon as the report began to circulate on social media platforms, the authorities began censoring or deleting it. The temple accused the monks of "forging material" and "distorting facts" - but it was too late. By late August, an investigation confirmed that Xuecheng, the abbot, had sexually harassed female disciples via text messages.

Xuecheng (R) the abbot of China's Longquan Monastery was one of China's most high-profile religious figures

He resigned to cheers that resounded across social media. The investigation had been handled by China's national religious council, and then handed onto the police and this was heralded as a big victory.

'Just forget about it, move on'

Shortly before the flurry of accusations came out a 19-year-old student from Gansu province jumped to her death because her allegation of sexual assault was not believed by her university or the local authorities.

The case caused a sensation online and one student at a different university, who wished to remain anonymous, told the BBC this is what finally prompted her to make a complaint about how she was sexually assaulted at her institution.

But support from her family was limited: "My parents don't understand why I insist on the investigation. They think I should forget about it, just move on.

Women in China face social and cultural pressures to toe the line

"I cried the whole night after that news, I feel what she felt. I was also 19 years old when I was sexually assaulted," she said.

"It shouldn't take our lives to fight against those people."

- Published6 January 2018

- Published2 August 2018

- Published12 January 2018