Would you share make-up with a stranger?

- Published

People in China can pay with their phones to enter make-up rooms, complete with cosmetics

A new trend of "shareable make-up rooms" aimed at urban women is igniting debate in China, as companies try new ways to grab a slice of the world's largest market for beauty products.

The rooms represent a new frontier in China's vast sharing economy. Some think they are an affordable way to get to use expensive make-up, while others shudder at the thought of sharing a lipstick with a stranger.

Although they have been springing up in many Chinese cities since late last year, a recent opening in eastern Wuhan has prompted a flood of discussion online.

But how do you use one, and are they likely to take off elsewhere?

How do they work?

Using their phones, customers scan a Quick Response (QR) code to pay a small fee, and enter a room with a chair and dressing table.

An array of beauty products is spread out on the table, including products from high-end Western brands.

Users can help themselves to a range of products: moisturisers, powders, eye shadows and lipsticks. The room also provides brushes and other application tools for people to use.

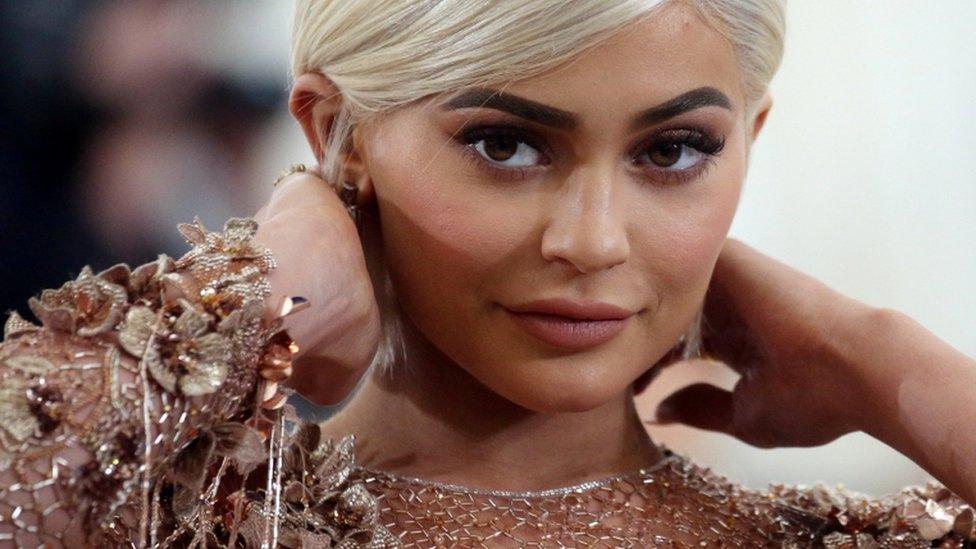

Users can help themselves to a variety of make-up products

Products in the Wuhan store are worth an estimated 4,000 yuan ($590; £460), according to the Chutian Metropolis Daily newspaper, so it is not surprising that CCTV watches over users as they beautify themselves.

It costs a small amount to use one of the rooms from anywhere between 15 and 45 minutes. In the Wuhan branch, the maximum a customer can expect to spend in one sitting is 58 yuan ($8.50; £6.70).

How are they viewed?

Young women who have tried the rooms and who the BBC spoke to had mostly positive impressions.

"I thought the shared make-up room was great, a very creative idea and a very novel invention," said Ms Liu, a woman in her twenties from Wuhan. Though she added: "I may not go often because I don't think they're very practical."

Another in Shanghai said she would use them again, because she felt her skin was especially damaged and she needed to have access to high-end products.

Online comments suggested a more mixed response.

Ms Feng told Pear Video that she would go back if make-up rooms provided authentic products

Some on China's Twitter-like Sina Weibo service said that they thought the concept would make money because it allows people to try products without "being bombarded by servicewomen at make-up counters", or forced into an expensive sale for something that might not be right for them.

One user in eastern Shandong province said she thought the room was "good", especially as disposable application tools were provided.

But others have concerns about the idea of sharing certain make-up products with strangers.

"Lipstick, for example, lots of people will use - that's not very hygienic," one Wuhan-based user told the Pear Video website.

"Cosmetics are personal items, I can't really accept this," another said. Others expressed concern about contracting viruses or skin conditions.

Chinese shareable make-up pods could ultimately attract up to 80 customers a day, one seller told the Beijing Youth Daily newspaper. But at present just a handful of people are visiting.

Ms Hu said that while the pods were a good idea in principle, sharing products like lipsticks was "unhygienic"

Are they really a new concept?

Self-contained shareable make-up pods are still a relatively novel idea, and they have only begun appearing in China since October 2018. They are largely being set up by private companies, not the cosmetic brands themselves, and are now found in major Chinese cities including Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Nanjing.

Large public dressing rooms offering similar services have been around in Japan and South Korea since as early as 2014.

The concept is part of a wave of shareable products that have hit the Chinese market in recent years. Well-known services include shareable bikes and phone chargers; but the country is also home to more obscure rentable goods, including umbrellas and basketballs.

China promotes shareable technologies for having both economic and environmental benefits, and in the case of luxury brands, helping Chinese users distinguish between fake and real goods in an increasingly saturated market.

So will they take off?

It is entirely possible, given the surging spending power of urban consumers and their willingness to spend their disposable cash on cosmetic products.

Research from OC&C Strategy Consultants says that China has the largest skincare market in the world, worth US$22bn, followed by the US.

Chinese women, according to the group's findings, have added more steps and products to their daily beauty routine in recent years, with the average Chinese woman surveyed having a 6 or 7-step daily skincare regime before applying make-up. Some had as many as nine daily steps.

Pascal Martin, a partner at the company, says China has a "massive [cosmetics] market with massive growth opportunity".

"International brands used to be dominant; it's a market in which everyone is competing," he says. "Yet, you can see Chinese brands gaining share year after year."

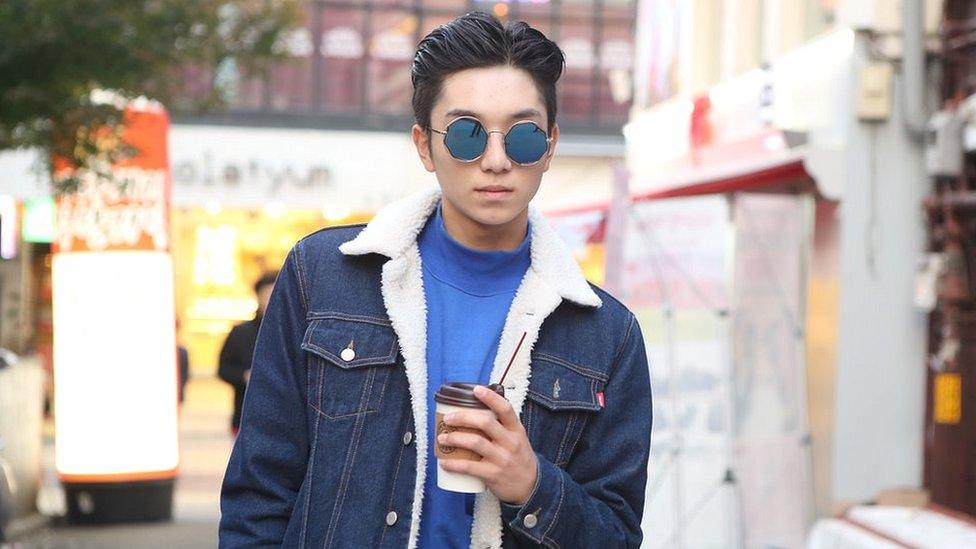

The appeal of young, fresh-faced celebrities like the popular TFBoys band has also led to a surge in spending on skincare products, with consumers splashing out on products because of the associations with their favourite icon.

The male beauty industry is also taking off in China

So-called "little fresh meats", men who have delicate or feminine features, have become key influencers among young, urban Chinese and are known to team up with local cosmetics brands.

Social media platforms have also seen a rising trend of video make-up tutorials.

And with young Chinese increasingly working longer hours outside the home, and spending more time online, the concept of a shareable make-up room may well prove desirable.

But Pascal Martin says that they are still in the experimental stage, and he is not convinced they will see mass take-off.

He says that concerns about hygiene could pose a significant risk.

"It is not impossible that the promoters of this concept may have convinced investors to put money in it, even if the concept is not bullet-proof.

"There are many examples in China of original concepts that suddenly take off with the backing of massive venture capital, and then hit reality before scaling down or disappearing."

BBC Monitoring, external reports and analyses news from TV, radio, web and print media around the world. You can follow BBC Monitoring on Twitter, external and Facebook, external.

- Published21 October 2018

- Published27 August 2018

- Published5 February 2018

- Published12 May 2018

- Published12 July 2018