China Muslims: Xinjiang schools used to separate children from families

- Published

The BBC's John Sudworth meets Uighur parents in Turkey who say their children are missing in China

China is deliberately separating Muslim children from their families, faith and language in its far western region of Xinjiang, according to new research.

At the same time as hundreds of thousands of adults are being detained in giant camps, a rapid, large-scale campaign to build boarding schools is under way.

Based on publicly available documents, and backed up by dozens of interviews with family members overseas, the BBC has gathered some of the most comprehensive evidence to date about what is happening to children in the region.

Records show that in one township alone more than 400 children have lost not just one but both parents to some form of internment, either in the camps or in prison.

Formal assessments are carried out to determine whether the children are in need of "centralised care".

Alongside the efforts to transform the identity of Xinjiang's adults, the evidence points to a parallel campaign to systematically remove children from their roots.

The Hotan Kindness Kindergarten, like many others, is a high security facility

China's tight surveillance and control in Xinjiang, where foreign journalists are followed 24 hours a day, make it impossible to gather testimony there. But it can be found in Turkey.

In a large hall in Istanbul, dozens of people queue to tell their stories, many of them clutching photographs of children, all now missing back home in Xinjiang.

"I don't know who is looking after them," one mother says, pointing to a picture of her three young daughters, "there is no contact at all."

Another mother, holding a photo of three sons and a daughter, wipes away her tears. "I heard that they've been taken to an orphanage," she says.

In 60 separate interviews, in wave after wave of anxious, grief-ridden testimony, parents and other relatives give details of the disappearance in Xinjiang of more than 100 children.

They are all Uighurs - members of Xinjiang's largest, predominantly Muslim ethnic group that has long had ties of language and faith to Turkey. Thousands have come to study or to do business, to visit family, or to escape China's birth control limits and the increasing religious repression.

But over the past three years, they have found themselves trapped after China began detaining hundreds of thousands of Uighurs and other minorities in giant camps.

The Chinese authorities say the Uighurs are being educated in "vocational training centres" in order to combat violent religious extremism. But evidence shows that many are being detained for simply expressing their faith - praying or wearing a veil - or for having overseas connections to places like Turkey.

For these Uighurs, going back means almost certain detention. Phone contact has been severed - even speaking to relatives overseas is now too dangerous for those in Xinjiang.

With his wife detained back home, one father tells me he fears some of his eight children may now be in the care of the Chinese state.

"I think they've been taken to child education camps," he says.

New research commissioned by the BBC sheds light on what is really happening to these children and many thousands of others.

Dr Adrian Zenz is a German researcher widely credited with exposing the full extent of China's mass detentions of adult Muslims in Xinjiang. Based on publicly available official documents, his report paints a picture of an unprecedented school expansion drive , externalin Xinjiang.

Campuses have been enlarged, new dormitories built and capacity increased on a massive scale. Significantly, the state has been growing its ability to care full-time for large numbers of children at precisely the same time as it has been building the detention camps.

And it appears to be targeted at precisely the same ethnic groups.

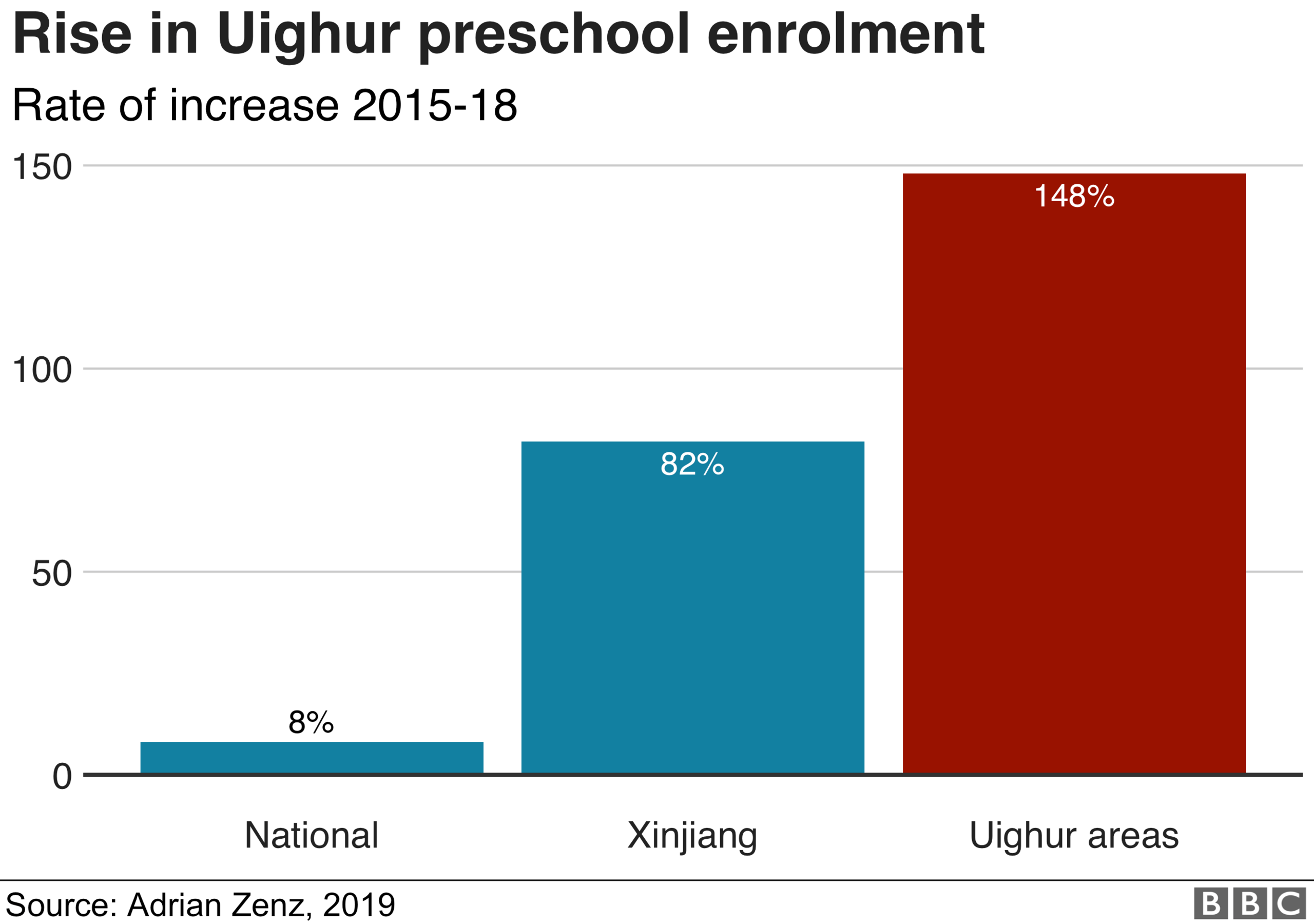

In just one year, 2017, the total number of children enrolled in kindergartens in Xinjiang increased by more than half a million. And Uighur and other Muslim minority children, government figures show, made up more than 90% of that increase.

As a result, Xinjiang's pre-school enrolment level has gone from below the national average to the highest in China by far.

In the south of Xinjiang alone, an area with the highest concentration of Uighur populations, the authorities have spent an eye watering $1.2bn on the building and upgrading of kindergartens.

Mr Zenz's analysis suggests that this construction boom has included the addition of large amounts of dormitory space.

Xinhe County Youyi Kindergarten has space for 700 children, 80% of whom are from Xinjiang's minority groups

Xinjiang's education expansion is driven, it appears, by the same ethos as underlies the mass incarceration of adults. And it is clearly affecting almost all Uighur and other minority children, whether their parents are in the camps or not.

In 2018 work began on a site for two new boarding schools in Xinjiang's southern city of Yecheng (known as Kargilik in Uighur).

Yecheng County Middle Schools 10 and 11

Dragging the slider reveals the pace of construction - the two middle schools, separated by a shared sports field, are each three times larger than the national average and were built in little more than a year.

In April last year, the county authorities relocated 2,000 children from the surrounding villages into yet another giant boarding middle school, Yecheng County Number 4.

Government propaganda extols the virtues of boarding schools as helping to "maintain social stability and peace" with the "school taking the place of the parents." And Mr Zenz suggests there is a deeper purpose.

"Boarding schools provide the ideal context for a sustained cultural re-engineering of minority societies," he argues.

Just as with the camps, his research shows that there is now a concerted drive to all but eliminate the use of Uighur and other local languages from school premises. Individual school regulations outline strict, points-based punishments for both students and teachers if they speak anything other than Chinese while in school.

And this aligns with other official statements claiming that Xinjiang has already achieved full Chinese language teaching in all of its schools.

The BBC visits the camps where China’s Muslims have their "thoughts transformed"

Speaking to the BBC, Xu Guixiang, a senior official with Xinjiang's Propaganda Department, denies that the state is having to care for large numbers of children left parentless as a result.

"If all family members have been sent to vocational training then that family must have a severe problem," he says, laughing. "I've never seen such a case."

But perhaps the most significant part of Mr Zenz's work is his evidence that shows that the children of detainees are indeed being channelled into the boarding school system in large numbers.

There are the detailed forms used by local authorities to log the situations of children with parents in vocational training or in prison, and to determine whether they need centralised care.

Mr Zenz found one government document that details various subsidies available to "needy groups", including those families where "both a husband and a wife are in vocational training". And a directive issued to education bureaus by the city of Kashgar that mandates them to look after the needs of students with parents in the camps as a matter of urgency.

Schools should "strengthen psychological counselling", the directive says, and "strengthen students' thought education" - a phrase that finds echoes in the camps holding their parents.

It is clear that the effect of the mass internments on children is now viewed as a significant societal issue, and that some effort is going into dealing with it, although it is not something the authorities are keen to publicise.

The BBC has found new evidence of the increasing control and suppression of Islam in China

Some of the relevant government documents appear to have been deliberately hidden from search engines by using obscure symbols in place of the term "vocational training". That said, in some instances the adult detention camps have kindergartens built close by, and, when visiting, Chinese state media reporters have extolled their virtues.

These boarding schools, they say, allow minority children to learn "better life habits" and better personal hygiene than they would at home. Some children have begun referring to their teachers as "mummy".

We telephoned a number of local Education Bureaus in Xinjiang to try to find out about the official policy in such cases. Most refused to speak to us, but some gave brief insights into the system.

We asked one official what happens to the children of those parents who have been taken to the camps.

"They're in boarding schools," she replied. "We provide accommodation, food and clothes… and we've been told by the senior level that we must look after them well."

Hotan Sunshine Kindergarten, seen through a wire fence

In the hall in Istanbul, as the stories of broken families come tumbling out, there is raw despair and deep resentment too.

"Thousands of innocent children are being separated from their parents and we are giving our testimonies constantly," one mother tells me. "Why does the world keep silent when knowing these facts?"

Back in Xinjiang, the research shows that all children now find themselves in schools that are secured with "hard isolation closed management measures." Many of the schools bristle with full-coverage surveillance systems, perimeter alarms and 10,000 Volt electric fences, with some school security spending surpassing that of the camps.

The policy was issued in early 2017, at a time when the detentions began to be dramatically stepped up. Was the state, Mr Zenz wonders, seeking to pre-empt any possibility on the part of Uighur parents to forcibly recover their children?

"I think the evidence for systematically keeping parents and children apart is a clear indication that Xinjiang's government is attempting to raise a new generation cut off from original roots, religious beliefs and their own language," he tells me.

"I believe the evidence points to what we must call cultural genocide."

- Published21 June 2019

- Published20 June 2019