China relocates villagers living in 800m-high cliffs in anti-poverty drive

- Published

The village made headlines after photos showed people scaling ladders to get home

They used to call an 800m-high cliff home, but dozens of villagers in China's Sichuan province have now been relocated to an urban housing estate.

Atulie'er village became famous after photos emerged showing adults and children precariously scaling the cliff using just rattan ladders.

Around 84 households have now been moved into newly built flats as part of a local poverty alleviation campaign.

It's part of a bigger national campaign to end poverty by the end of 2020.

'So happy I got a house'

Atulie'er village made headlines in 2016 when it was revealed that its villagers had to scale precarious ladders to get home, carrying babies and anything the village needed.

Soon afterwards the government stepped in and replaced these with steel ladders.

The households have now been moved to the county town of Zhaojue, around 70km away.

They will be rehoused in furnished apartment blocks, which come in models of 50, 75 and 100 sq m - depending on the number of people in each household.

It'll be a big change for many of these villagers, who are from the Yi minority and have lived in Atulie'er for generations.

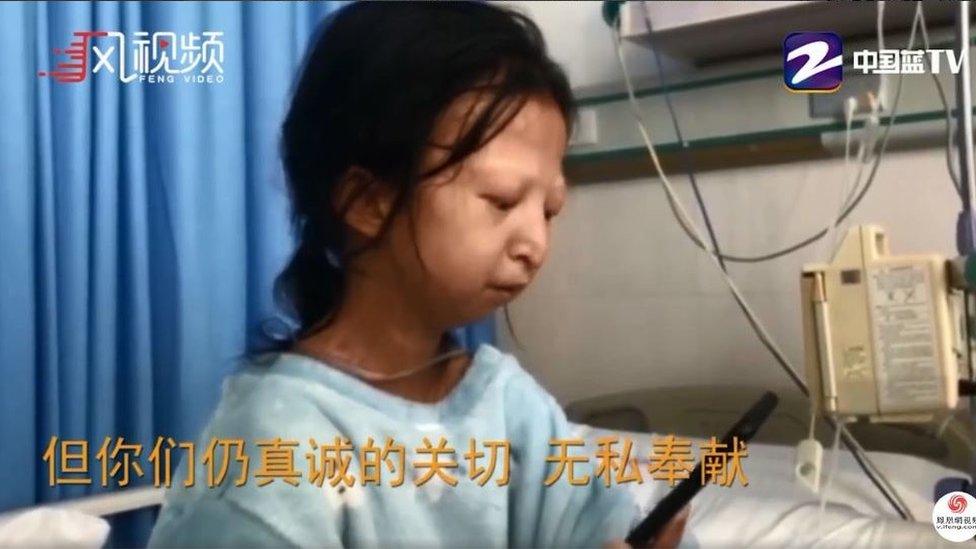

Photos on Chinese state media showed villagers beaming, one of them telling state media outlet CGTN , externalthat he was "so happy that I got a good house today".

'Big financial burden'

According to Mark Wang, a human geography professor at the University of Melbourne, such housing schemes are often heavily subsidised by the government, typically up to 70%. However, in some instances families have been unable to afford the apartments despite the subsidies.

"For some really poor villages, the 30% may still be difficult for them to pay, so they end up having to borrow money - [ironically] causing them even more debt," he told BBC News.

"For the poorest, it's a big financial burden and so in some instances, they might have to stay."

According to Chinese state media outlet China Daily, each person will have to pay 2,500 yuan ($352; £288) for this particular move - so for a family of four, the cost would come up to 10,000 yuan.

This is the journey the villagers had to make to get home

This is quite a low price, says Mr Wang, as he had heard of people having to pay up to 40,000 yuan for other relocation projects.

Mr Wang says in most poverty resettlement campaigns, villagers are given a choice whether or not to move, and are not usually moved into cities from the countryside.

"In most instances it's a move to a county town or a suburb. So it's not like they're moving to a big city. Not everyone wants an urban life and most of those who do would have already left these villages and moved to the big cities," he says.

"Usually the government [puts a limit] on the resettlement distance. This is in most people's favour because it means they can keep their farm land, so that's very attractive."

The Atulie'er villagers will share this new apartment complex with impoverished residents across Sichuan province.

The villagers will be living in these apartment buildings

Around 30 households will remain in the Atulie'er village - which is set to turn into a tourism spot.

According to Chinese state media outlet China Daily, these households will effectively be in charge of local tourism, running inns and showing tourists around.

The county government has ambitious plans - planning to install a cable car to transport tourists to the village and to develop some surrounding areas. An earlier report said there were plans to turn the village into a vacation resort, with state media saying the state would pump 630 million yuan into investment.

Though these developments are likely to bring more jobs to the area, it's not clear what safeguards are in place to make sure that the site's ecological areas are protected and not at risk of being overdeveloped.

Do people in China's rural communities think poverty reduction can work?

Chinese President Xi Jinping has declared that China will eradicate poverty in China by 2020.

There's no one standard definition of poverty across all of China, as it differs from province to province.

One widely quoted national standard is 2,300 yuan ($331; £253) net income a year. Under that standard, there were around 30 million people living in poverty across the whole of China in 2017.

But the 2020 deadline is approaching fast - and Mr Wang says the plan could be derailed by the virus outbreak.

"Even without Covid-19 it would be hard to meet this deadline and now realistically, it has made it even more difficult."

- Published10 January 2020

- Published21 November 2016

- Published3 January 2018

- Published1 November 2019