Coronavirus: Fact-checking claims it might have started in August 2019

- Published

The coronavirus outbreak was first seen in Wuhan - but was it circulating earlier than thought?

There's been criticism of a study from the US suggesting that the coronavirus could have been present in the Chinese city of Wuhan as early as August last year.

The study by Harvard University, widely publicised when released earlier this month, has been dismissed by China and had its methodology challenged by independent scientists, external.

We've looked at the techniques used in the report and found shortcomings both in the use of satellite imagery and online search data, raising significant doubts about its overall findings.

What did the research say?

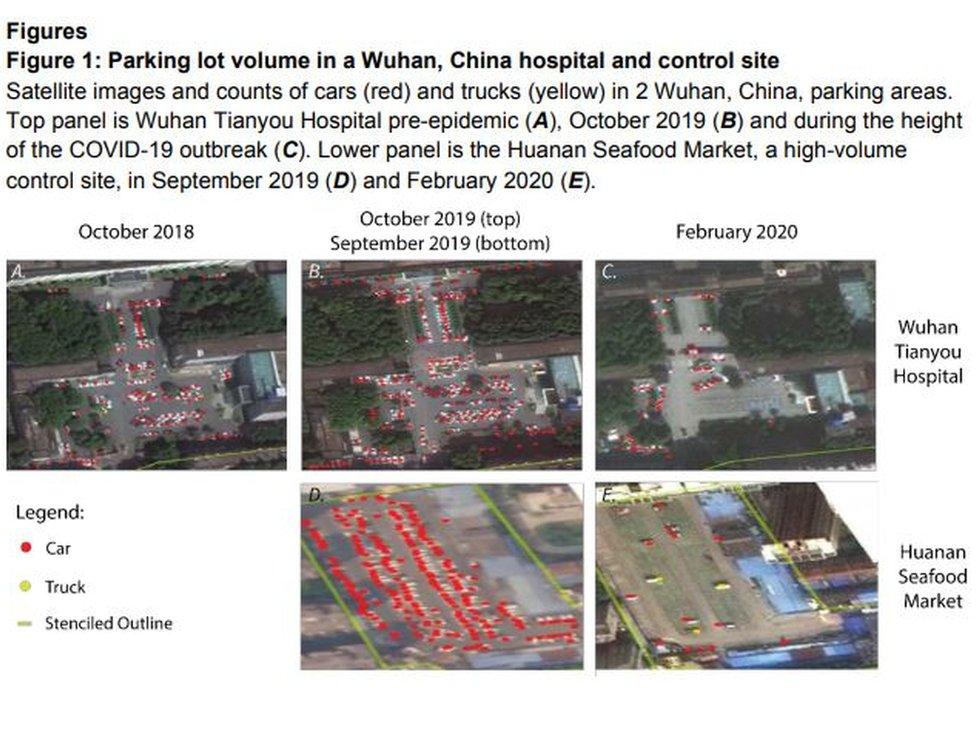

The research is based on satellite imagery of traffic movements around hospitals in Wuhan and the tracking of online searches for specific medical symptoms.

It says there was a noticeable rise in vehicles parking outside six hospitals in the city from late August to 1 December 2019.

This coincided, says the Harvard report, with an increase in searches for possible coronavirus symptoms such as "cough" and "diarrhoea".

The researchers monitored Wuhan traffic patterns

This would be an important finding because the earliest reported case in Wuhan wasn't until the beginning of December.

The academics write: "While we cannot confirm if the increased volume was directly related to the new virus, our evidence supports other recent work showing that emergence happened before identification at the Huanan Seafood market."

The Harvard study has gained a lot of traction in the media, with President Trump, who has been highly critical of China's pandemic response, tweeting a Fox News item highlighting the researchers' findings, external. The tweet has been viewed more than three million times.

So, does their evidence stand up?

The study, which hasn't been peer-reviewed - the process by which academic papers get checked by other scientists - claims there was an increase in online queries for coronavirus symptoms, particularly "diarrhoea", on popular Chinese search engine Baidu.

However, Baidu company officials have disputed their findings, saying there was in fact a decrease in searches for "diarrhoea" over this period.

So, what's going on?

The term used in the Harvard University paper actually translates from Chinese as "symptom of diarrhoea".

We checked this on Baidu's tool that allows users to analyse the popularity of search queries, like Google Trends.

The search-term "symptom of diarrhoea" does indeed show an increase in queries from August 2019.

However, we also ran the term "diarrhoea", a more common search-term in Wuhan, and it actually showed a decrease from August 2019 until the outbreak began.

A lead author of the Harvard paper, Benjamin Rader, told the BBC that "the search term we chose for 'diarrhoea' was chosen because it was the best match for confirmed cases of Covid-19 and was suggested as a related search term to coronavirus".

We also looked at the popularity of searches for "fever" and "difficulty in breathing", two other common symptoms of coronavirus.

Searches for "fever" increased a small amount after August at a similar rate to "cough", and queries for "difficulty in breathing" decreased in the same period.

There have also been questions raised about the study using diarrhoea as an indicator of the disease.

A large-scale UK study, external of nearly 17,000 coronavirus patients found that diarrhoea was the seventh most common symptom, well below the top three: cough, fever and shortness of breath.

What about the number of cars?

Across the six hospitals, the Harvard study reported a rise in cars in hospital parking lots from August to December 2019.

However, we've found some serious flaws in their analysis.

The researchers studied and annotated satellite images showing Wuhan hospitals

The report states that images with tree cover and building shadows were excluded to avoid over or under-counting of vehicles.

However, satellite images released to the media show large areas of hospital car parks blocked by tall buildings which means that it's not possible to accurately assess the number of cars present.

To show this, we've selected two of these images taken at different times of the Hubei Women and Children Hospital.

The first is of the healthcare centre in October 2018 - and we've marked with white boxes the parking area obscured by buildings.

This second image below - taken in October 2019 - shows the same hospital at a different angle. In this image there's a full view of the spaces previously hidden by the buildings.

Looking at other satellite images used in the Harvard report, we found car parks in other hospitals obscured in a similar way.

There's also an underground car park at Tianyou Hospital, which is visible on Baidu's street view function, but only the entrance is in view on satellite imagery - not the cars underneath the ground. Report author Benjamin Rader said "we definitely can't account for underground parking in any time period of the study and this is one of the limitations of this type of research."

The researchers could have compared their data with other Chinese cities to see if the rises in hospital traffic and search queries were specific to Wuhan, where the outbreak first came to light, or whether similar patterns where observed elsewhere.

The study findings - that coronavirus may have been present in Wuhan as far back as last August - are for the reasons we've highlighted, highly problematic.

There is, however, still much we don't know about the early onset of the virus in China - both when and how the first cases emerged.

A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

IMPACT: What the virus does to the body

RECOVERY: How long does it take?

LOCKDOWN: How can we lift restrictions?

ENDGAME: How do we get out of this mess?