Li Zhensheng: Photographer of China's cultural revolution

- Published

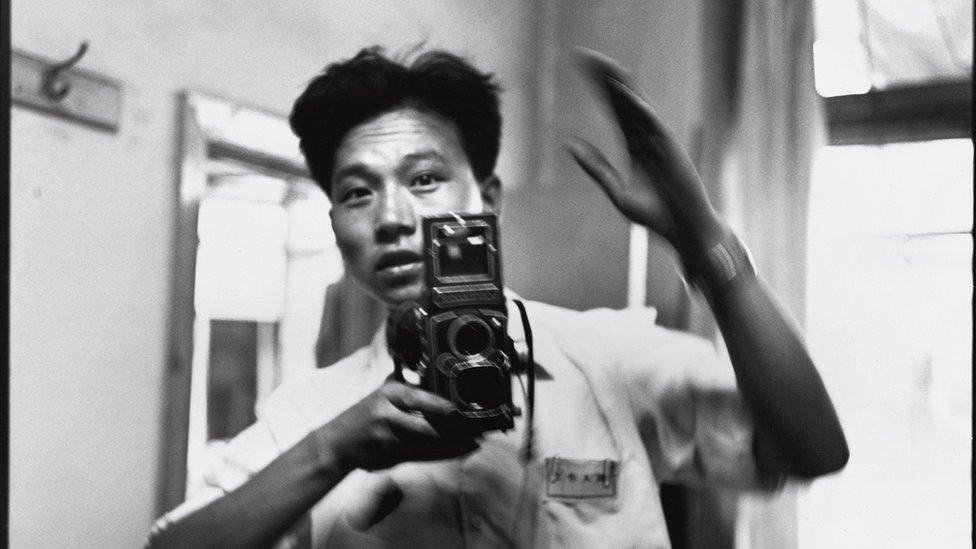

Li Zhensheng in his youth

Li Zhensheng risked his life in his determination to capture China's Cultural Revolution on film.

As a staff photographer working for a state-run newspaper, Li Zhensheng had rare access to people and places during one of the most turbulent periods of the 20th Century.

He took tens of thousands of photos, some of which were published, others stored in the floorboards of his flat for fear of punishment.

What he didn't know then was that these hidden images would one day find their way out into the world.

The 79-year-old died earlier this week of cerebral haemorrhage in the US, said his Hong Kong publisher, the Hong Kong University Press.

"I have pursued witnessing and recording history all my life," his publisher records him as saying before his death. "Now I rest in history."

Red-colour News Soldier

Born in 1940 to a poor family in the Chinese province of Liaoning, external, Li grew up under difficult circumstances.

His mother died when he was three and he grew up helping his father in the fields until he was 10. Only then did he start school, but quickly rose to the top of his class.

He earned a spot at the Changchun Film School and eventually became a staff photographer for the Heilongjiang Daily newspaper in north-eastern China.

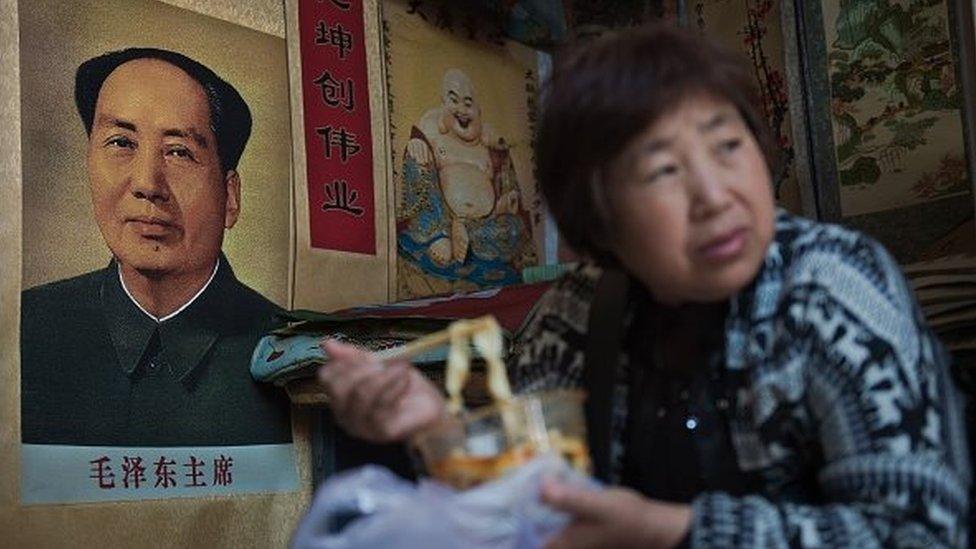

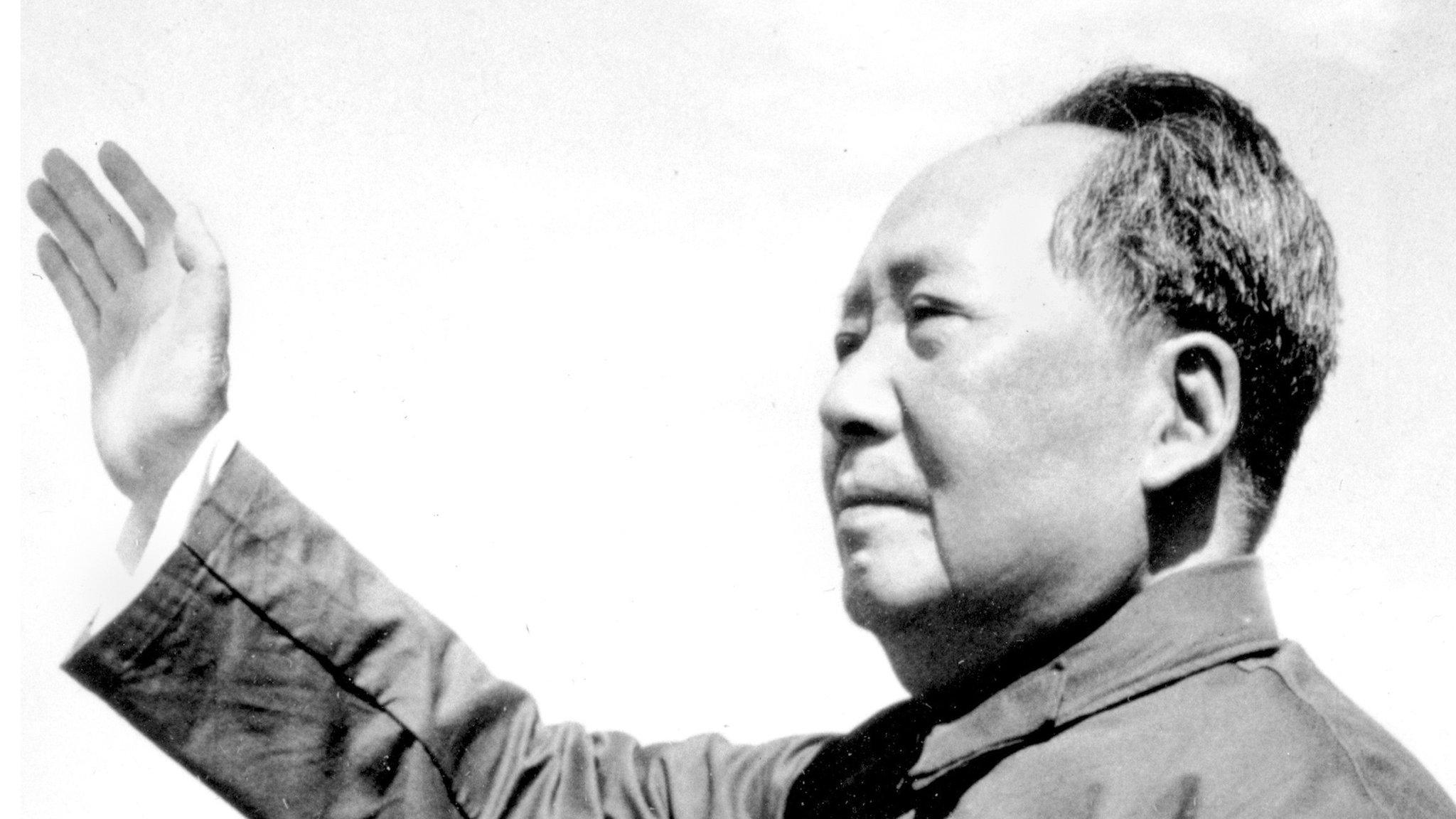

This job came during one of the most brutal periods in China's history. The Cultural Revolution began in 1966 when Communist leader Mao Zedong began a campaign to eliminate his rivals.

Swimmers reading Mao's 'Little Red Book'

Mao mobilised thousands of Chinese youth to destroy the "four olds" in Chinese culture - old customs, habits, culture and thinking.

Colleges were shut so students could concentrate on "revolution", and as the movement spread, they began to attack almost anything and anybody that stood for authority.

Children turned on their parents and students turned on their teachers, intellectuals were exiled. Thousands were beaten to death or driven to suicide.

Li's new job left him in the unusual position of being able to record the violence and brutality that was happening around him.

He noticed that the Red Guards - militant students - were getting access to photograph anything they wanted, so he decided to make an armband emblazoned with the words "Red-colour news soldier".

"My work meant that I could take photographs of people being persecuted without being harassed," he told the BBC in an earlier interview.

"I realised that this turbulent era must be recorded. I didn't really know whether I was doing it for the revolution, for myself, or for the future."

But he realised that the sensitive nature of the images could make him a target, so he hid the negatives away under the floorboards of his flat - around 20,000 of them.

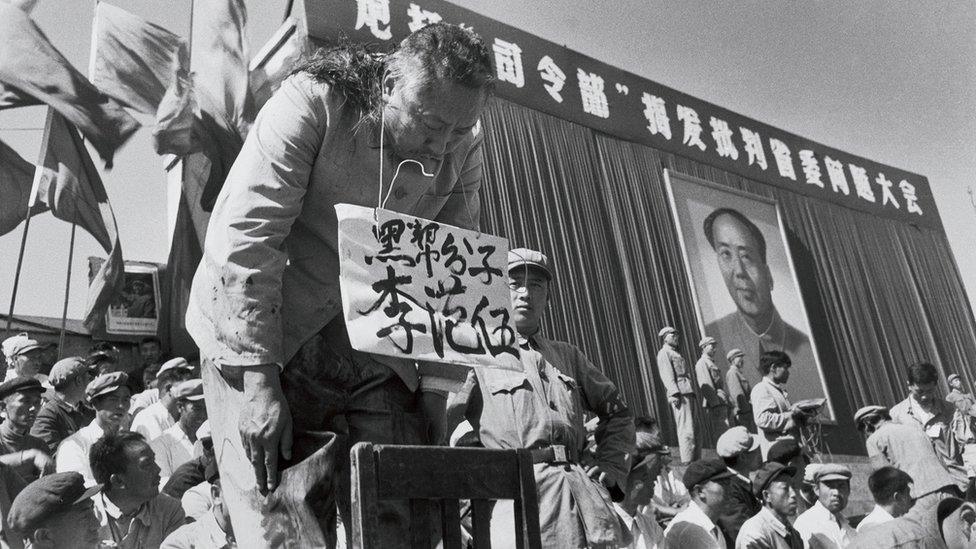

Heilongjiang's provincial governor had his hair shaved after being accused of growing it long like Chairman Mao

When he was eventually accused of counter-revolutionary activities in 1968, his flat was ransacked by the authorities but the negatives remained undiscovered.

If they had been found, Mr Li would have been severely punished and they would almost certainly have been destroyed.

"It was kind of risky," he admitted. "When I took these photos I was not sure how useful they would be."

Li's photos were safe but he was not - he was denounced and along with his wife, was forced to undergo hard labour for two years.

Upon his release he returned to his flat, and found the images safe and preserved.

He eventually became a professor at a university in Beijing and in the 1980s - a period of time when China saw a sliver of press freedom - his works were exhibited at a photography event in Beijing.

Red Guards were so known for red bands they wore around their arms

It was then that his pictures were discovered by Robert Pledge of Contact Press Images (CPI), who later went on to publish a book with Li's images.

The book's name? Red-colour News Soldier.

"We will be forever grateful to Li for having risked so much to doggedly preserve his images at a time when most of his colleagues agreed to allow their politically 'negative negatives' to be destroyed," said Pledge.

He revealed that Li kept all his photos in small brown paper envelopes. On each envelope he wrote detailed captions in delicate Chinese calligraphy. Communes and counties, people's names, official titles and specific events were all carefully noted.

His photos were eventually exhibited in dozens of countries.

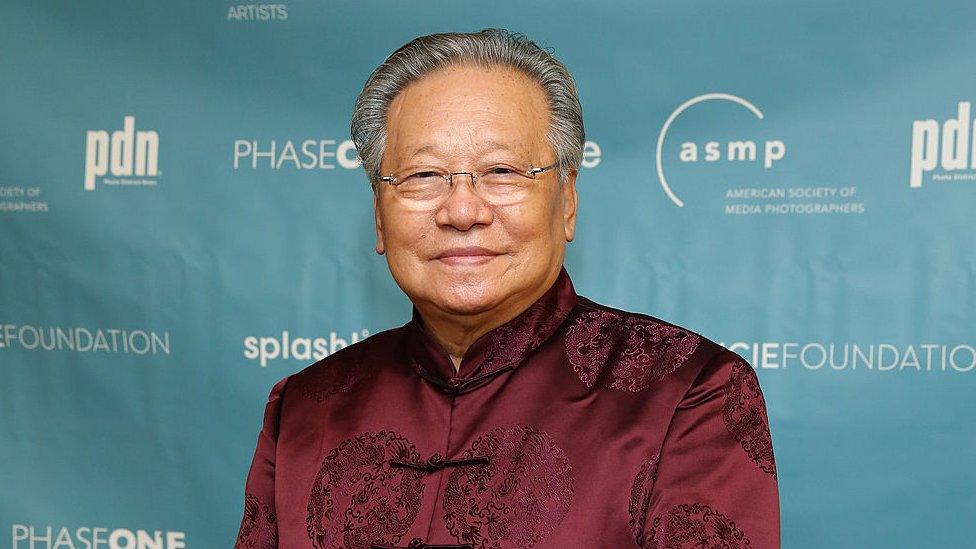

Li at the Lucie Awards

In 2013, he was awarded the Lucie Award - known as the Oscars of the photography world.

And in 2018, his works were printed with Chinese text for the first time and published in Hong Kong.

"No single photographer covered the revolution more thoroughly and completely than Li," said Contact Press Images in a statement following his death.

"He leaves an inestimable photographic legacy. He will be sorely missed."

- Published16 May 2016

- Published13 October 2012

.jpg)

- Published16 May 2016

- Published15 May 2016

- Published16 May 2016