Hong Kong: First arrests under 'anti-protest' law as handover marked

- Published

Hundreds have been arrested as Hong Kong's national security law kicks in

Hong Kong police have made their first arrests under a new "anti-protest" law imposed by Beijing, as crowds marked 23 years since the end of British rule.

Ten people were held accused of violating the law, including a man with a pro-independence flag. About 360 others were detained at a banned rally.

The national security law targets secession, subversion and terrorism with punishments up to life in prison.

Activists say it erodes freedoms but China has dismissed the criticism.

Hong Kong's sovereignty was handed back to China by Britain in 1997 and certain rights were supposed to be guaranteed for at least 50 years under the "one country, two systems" agreement.

The UK has now said up to three million Hong Kong residents will be offered the chance to settle in the UK and ultimately apply for citizenship.

On Wednesday, thousands gathered for the annual pro-democracy rally to mark the handover anniversary, defying a ban by authorities who cited restrictions on gatherings of more than 50 people because of Covid-19.

Many residents worry the new law means the end of the "one country, two systems" principle

Police used water cannon, tear gas and pepper spray on demonstrators. Seven officers were injured, external, including one officer who was stabbed in the arm by "rioters holding sharp objects", police said. The suspects fled and bystanders offered no help, they added.

One of the 10 arrested under the new law, adopted in the wake of last year's widespread unrest, was holding a "Hong Kong Independence" flag. However, some Twitter users said the picture appeared to show a small "no to" written in front of the slogan. The man has not been identified, and it was not clear whether he would be prosecuted.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The legislation has been condemned by numerous countries and human rights activists.

UK Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab called the measures a "flagrant assault" on freedoms of speech and protest.

The UK has also updated its travel advice on Hong Kong, external, saying there is an "increased risk of detention, and deportation for a non-permanent resident".

US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo said China had broken its promise to Hong Kong's people.

But in Beijing, foreign ministry spokesman Zhao Lijian urged countries to look at the situation objectively and said China would not allow foreign interference in its domestic affairs.

Dominic Raab: China is in "clear and serious breach" of the Joint Declaration

What does the new law say?

Crimes of secession, subversion, terrorism and collusion with foreign forces are punishable by a minimum sentence of three years, with the maximum being life. It also says:

Damaging public transport facilities - which often happened during the 2019 protests - can be considered terrorism

Beijing will establish a new security office in Hong Kong, with its own law enforcement personnel - neither of which would come under the local authority's jurisdiction

Inciting hatred of China's central government and Hong Kong's regional government are now offences under Article 29

The law can also be broken from abroad by non-residents under Article 38, and this could mean that foreigners could be arrested on arrival in Hong Kong

Some trials will be heard behind closed doors

Beijing will also have power over how the law should be interpreted, and not any Hong Kong judicial or policy body. If the law conflicts with any Hong Kong law, the Beijing law takes priority.

Zhang Xiaoming, executive deputy director of Beijing's Hong Kong and Macau Affairs Office said the law would not be applied to offences committed before it was passed and that suspects arrested in Hong Kong on charges of violating the law may be tried on the mainland.

Chief Executive Carrie Lam, Hong Kong's pro-Beijing leader, said the law would "restore stability" and that it was "considered the most important development in relations between the central government and Hong Kong since the handover".

Hong Kong's new security law

THE TEXT: What it is and why Hong Kong is worried

WHAT COULD HAPPEN: Life sentences for breaking the law and more

RESIDENTS REACT: 'End of one country, two systems'

PRO-DEMOCRACY MOVEMENT: Minutes after new law, voices quit

What is happening with the protests?

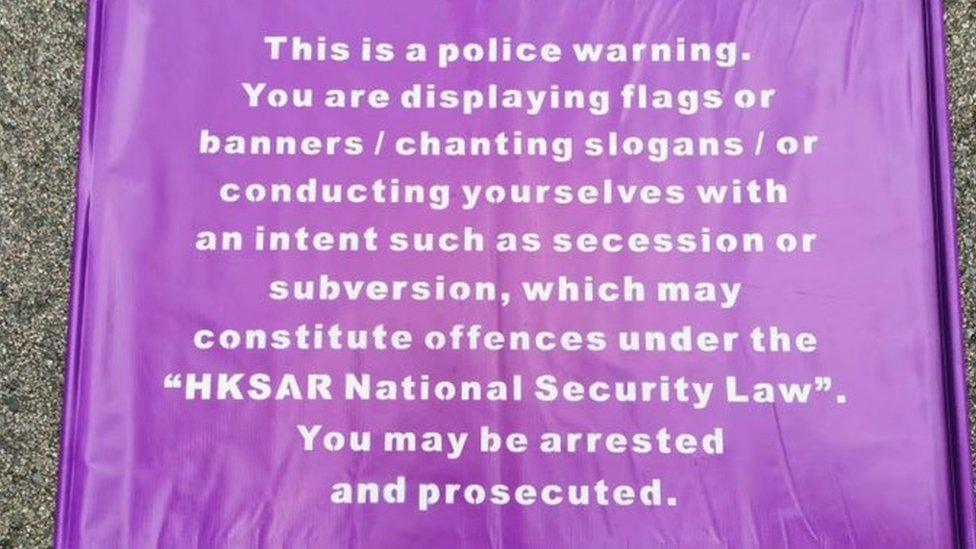

Demonstrators in the Causeway Bay district chanted "resist till the end" and "Hong Kong independence", with police using a flag to warn protesters that certain slogans and banners might now constitute serious crimes.

Police are carrying this banner warning protesters about the new law

Ahead of the protest, pro-democracy activist Tsang Kin-shing, of the League of Social Democrats, warned there was a "large chance of our being arrested", saying: "The charges will not be light, please judge for yourself."

A man who gave his name as Seth, 35, told Reuters: "I'm scared of going to jail but for justice I have to come out today, I have to stand up."

A turning point

By Michael Bristow, BBC World Service Asia-Pacific editor

The law gives Beijing extensive powers to shape life in the territory that it has never had before. It not only introduces a series of tough punishments for a long list of crimes, it changes the way justice is administered.

Trials can be held in secret - and without a jury. Judges can be handpicked. The law reverses a presumption that suspects will be granted bail. There appears to be no time limit on how long people can be held.

Crimes are described in vague terms, leading to the possibility of broad interpretation, and the right to interpret lies only in Beijing. Foreign nationals outside of Hong Kong face prosecution.

Most cases will be handled in Hong Kong, but the mainland can take over "complex", "serious" or "difficult" cases. Whether or not you think the legislation was necessary, it is impossible to deny its significance. As Hong Kong's leader Carrie Lam put it: this is a turning point.

Read more from our correspondent: Why people are scared of the new law

What reaction has the new law drawn?

Minutes after the law was passed on Tuesday, pro-democracy activists began to quit, fearful of the punishment the new law allows.

Ted Hui, an opposition legislator, told the BBC: "Our freedom is gone, our rule of law, our judicial independence is gone".

Ai Weiwei: "Today is the darkest day for Hong Kong"

The EU expressed "grave concerns" that the law could "seriously undermine" the city's independence.

In the US, lawmakers from both parties have launched a bill to give refugee status to Hong Kong residents at risk of persecution, reported local media outlets.

Taiwan's government has said it will set up a special office to help those in Hong Kong facing immediate political risks.

Jimmy Lai: China's security law 'spells the death knell for Hong Kong' (Interview from June 2020)

- Published1 July 2020

- Published1 July 2020

- Published30 June 2020

- Published30 June 2020

- Published19 March 2024

- Published28 May 2020