Hong Kong security law: Why we are taking our BNOs and leaving

- Published

Since China imposed a draconian national security law on Hong Kong, a lot of dinner party chatter in this protest-minded city has been about personal exit strategies. For up to three million Hongkongers, the exit could come in the form of a British National (Overseas) passport. Will they really leave - and what of those left behind?

Michael and Serena have decided to leave Hong Kong for good and settle in the UK, a country they have never set foot in.

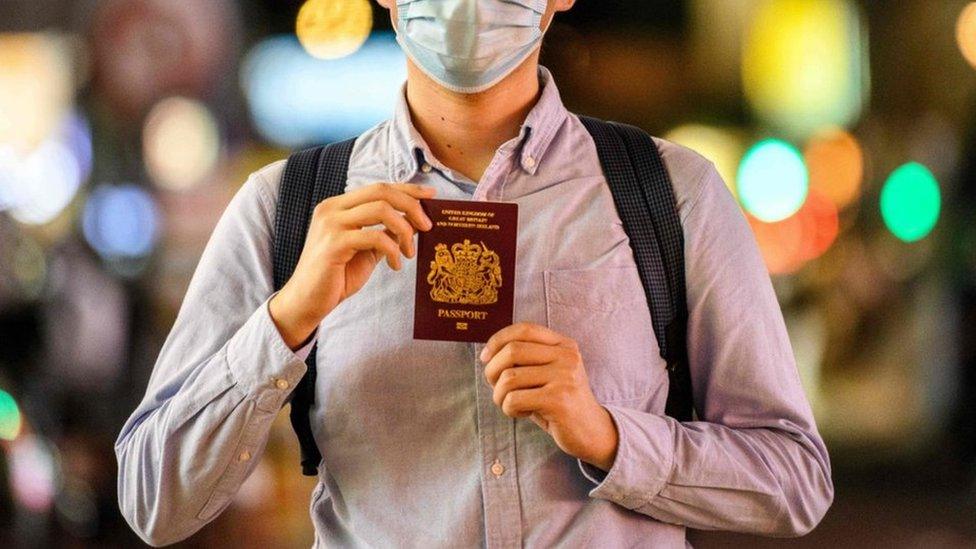

The couple have British National (Overseas) - or BNO - passports, which were issued to Hong Kong residents that registered before the city was handed back to China on July 1997.

Essentially a travel document with rights for some consular assistance, its usefulness seemed limited to many for anything but easier access to the UK and European travel. Some people went for it anyway. Why not, went the thinking for many Hongkongers.

Hong Kong was engulfed by increasingly violent protests last year

Michael and Serena are the embodiment of the comfortable prosperity common in Hong Kong: well-travelled with a 13-year-old daughter, they are both middle managers in a bank and bought a flat many years ago. It is a lot to give up.

They say that Hong Kong has become unrecognisable in its handling of the months-long protests triggered by a bill which proposed to allow extradition to mainland China. What the couple saw was a government which did not listen to the people, and police force that showed little restraint.

Their daughter has been deeply affected by the protests, even though the family did not take part because the couple work at a Chinese bank, where an employee was fired for protesting.

"She has been very angry and upset. She kept asking why the authorities could treat us like that?" Serena said, adding that their daughter had told them she wanted to study abroad.

The controversial national security law, which took effect last week, was the last straw.

"The articles of the national security law are outrageous," said Michael. Serena said she did not believe Beijing's claims that the claim that law would only target "a tiny number of people".

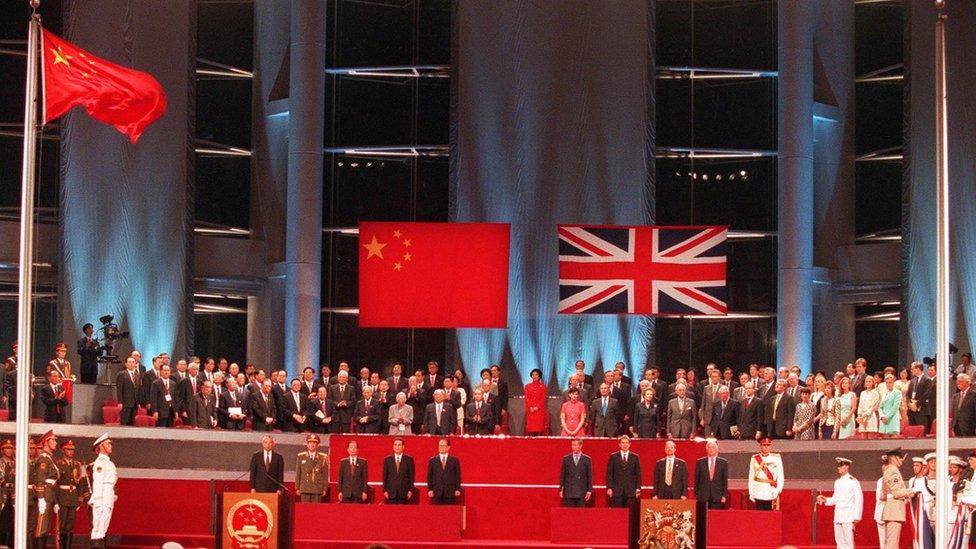

PM Boris Johnson says the new law "violates Hong Kong's high degree of autonomy"

The UK now wants to offer BNO passport holders citizenship rights after six years of stay, arguing that China has breached the Sino-British Joint Declaration by enacting the national security law, which violates the city's high degree of autonomy and infringes the civil liberties of Hong Kong residents.

Michael and Serena's original plan was to only send their daughter to study abroad, but now moving to the UK as a family has become their first choice. Last November, they renewed their long-expired BNO passports, thinking that it could become useful - a hedge against an uncertain future.

"I thought the UK would only offer citizenship to BNO passport holders as a last resort. I didn't think it would happen so soon, but all of a sudden great changes are happening," Michael said.

In the week since China announced the new security law, the story of Michael and Serena has become more common.

The people without BNO passports

BNO passports were issued to people who registered before the former British colony was handed back to China

Currently, there are about 350,000 BNO passport holders in Hong Kong, and the UK government estimates that there are about 2.9 million BNOs in total.

Hong Kong residents born after the 1997 handover are not eligible for the BNO passport - and those who did not apply for one before the handover are not allowed to do so now.

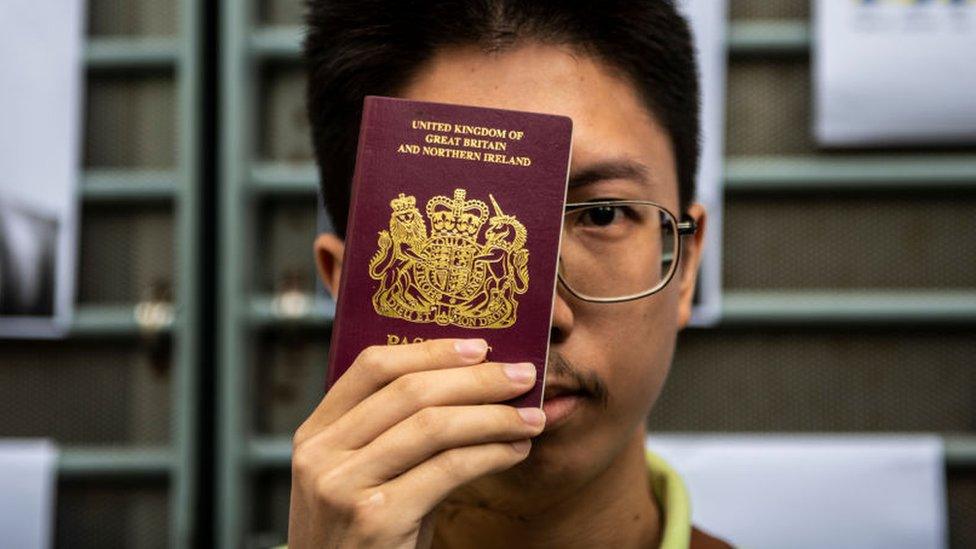

Helen was born in 1997 before the handover, but her parents did not apply for a BNO passport for her because she was a baby.

"I am not sure if I want to go. But this is my right. Compared to the UK, I like Hong Kong more. But I should have had a BNO passport," she said, admitting that she blamed her parents a little for not applying for one for her back then.

About 350,000 Hong Kong residents are BNO passport holders as of February

It is difficult to gauge the number of Hong Kong residents who will take up the UK's offer at this moment - but interest is running high, especially after the UK's announcement on July 1. On that day, Mr Raab told the House of Commons: "We will not look the other way on Hong Kong, and we will not duck our historic responsibilities to its people."

Ben Yu, who works for an immigration consultancy in the UK, said: "My Hong Kong-based colleague receives 30 to 40 messages on Facebook every day. His WhatsApp has received hundreds of messages asking about moving to the UK by all routes, including BNOs and other visas. The messages come in 24/7 non-stop since then."

The number of BNO renewals appears to be driven by political upheavals in Hong Kong. In 2018, about 170,000 BNO passports were in circulation. The next year, the number jumped to more than 310,000.

Hong Kong residents on controversial security law

During the colonial days, Hong Kong was always described as a borrowed place on borrowed time - and it is no stranger to waves of emigration. Between 1984 and 1997, between about 20,000 and 66,000 people left the city every year.

The imminent wave of emigration will also likely look different to those in the past. "A lot of them returned to Hong Kong either before 1997 or after 1997, when they had seized their safety outlets when they had got their foreign passports, when they saw that the political nightmare had not occurred as predicted," said Professor Ming Sing, who teaches politics at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. "For the current wave, should it happen, I guess we will see a higher proportion of them is going to be a one-way ticket," he said.

"A lot of them see that the legislation of the national security law which has been imposed from the top is not only draconian in nature, but it also reflects Beijing reneging on its promise. Not only its failure to protect Hong Kong's freedoms under the Joint Declaration and under the Basic Law," he said, adding that he thinks more young people, many of them are protesters, will exit Hong Kong.

What comes next?

In the city of 7.5 million, about 800,000 people have British, Australian, Canadian, or American passports - including expats.

Beijing has expressed anger over the UK's plan to offer citizenship to BNO passport holders in Hong Kong. China's Ambassador to the UK Liu Xiaoming said on Monday the move constitutes "gross interference in China's internal affairs"

"No one should underestimate the firm determination of China to safeguard its sovereignty, security and development interests," he said.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The Chinese Embassy also said in a statement all "Chinese compatriots residing in Hong Kong are Chinese nationals".

In an earlier interview with ITV, Mr Raab said there is little the UK could do if China doesn't allow Hong Kong residents to come to the UK.

"It is hard to predict what consequences Beijing has in mind. Probably more diplomatic ones in the form of a counter-measure, which does not necessarily need to be in the same form but should not be disproportionate," said Simon Young, a legal scholar at the University of Hong Kong.

Benedict Rogers, co-founder and chair of advocacy group Hong Kong Watch, described the BNO offer as "generous, courageous and welcome".

Hong Kongers with British passports are divided over whether to leave the country

But the rescue element should be a last resort, Mr Rogers said. "We should be working to ensure the conditions are met whereby HongKongers can continue their way of life, with the freedoms they were promised, without having to flee their homes. But the reality is that now, for some, it is already too late and they will need a place of sanctuary."

Michael and Serena are making preparations for a new life in the UK, but they did not succeed at convincing their older son, who is turning 18 soon, to leave with them. He will live with his grandparents after the rest of the family has moved.

"My son says he doesn't want to leave Hong Kong, because he thinks Hong Kong belongs to him," Serena said.

Some names have been changed.