What my grandfather's life taught me about China and America

- Published

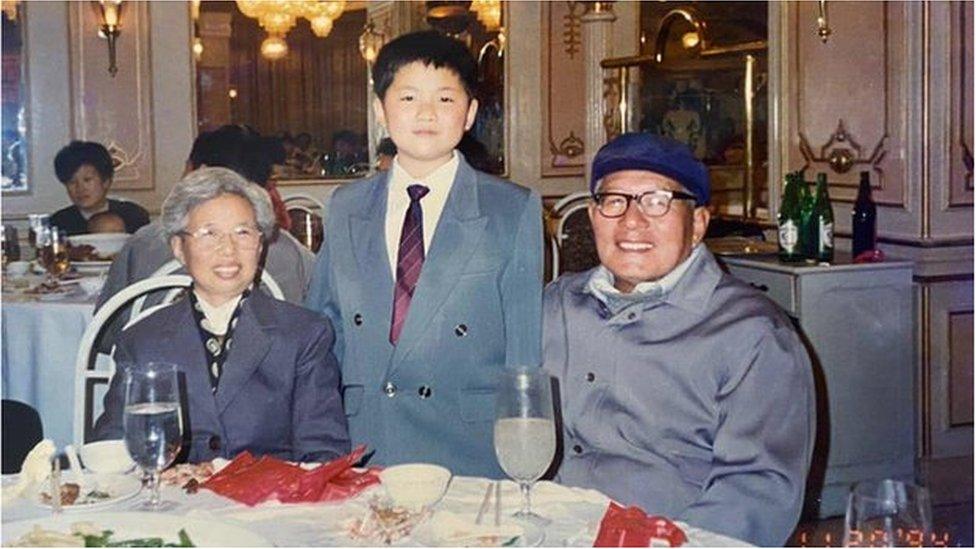

Vincent with his grandparents in 1994

When my grandfather was in his mid-20s, he made a life-changing choice to stay in mainland China - one that would alter the course of my family's story.

It also gave him a front-row seat on much of modern Chinese history.

And in an unexpected way, it would shape his view of the United States, which is now questioning the benefits of its 40-year engagement with China as relations plummet.

My grandfather Ni Xili died in September aged 95, prompting me to reflect on the tumultuous times he lived through - and what America has meant to many Chinese people of that generation.

What does the future hold for this relationship in the years to come?

Surviving war and revolution

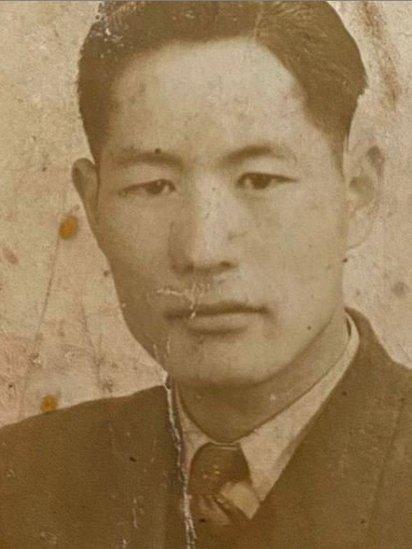

Ni Xili was born in the inter-war years, in January, 1925. But that is only according to his death certificate. Like many Chinese people of that generation, his exact birth day is not known because the registration system barely existed at the time.

Ni Xili as a young man

What he remembered is that he was born in the year of the rat - the lunar Chinese zodiac - during winter. The rat is the same zodiac as mine, although we were six decades apart in age.

As a family we were prepared for him to die - he'd been unwell since the start of the year and had been in and out of hospital. But when the news reached me in London on a Friday morning in September, it was still a shock.

There was a sense of deep regret. I had promised to go back to see him once the pandemic was over. I missed the days when we sat next to each other talking about everything. This will now never happen.

I grew up under the same roof as my grandparents in a three-storey house built by their four sons in eastern China.

Grandfather never spent much time talking about his past but over the years, through stories retold by my father and three uncles, I learnt that he'd had a turbulent life - one that resonates in today's pandemic-stricken world when many people feel they are prevented from realising their ambitions and chasing their dreams.

He, too, had a dream - a humble one: just to stay alive. Shortly after he was born the Chinese civil war broke out. When he was almost a teenager Japan invaded China. The horror of the killing shaped his view of a country living in fear and humiliated by foreign occupation.

Then, when the fight against the Japanese finally ended, civil war resumed. My grandfather, like many of his friends, fought alongside the Nationalists. By the late 1940s it became clear the Communists were going to take over, and he was given the choice to leave for the island of Taiwan, along with other defeated Nationalists.

But Ni Xili decided to stay - because my grandmother was pregnant with their first child. He also didn't want to leave his homeland.

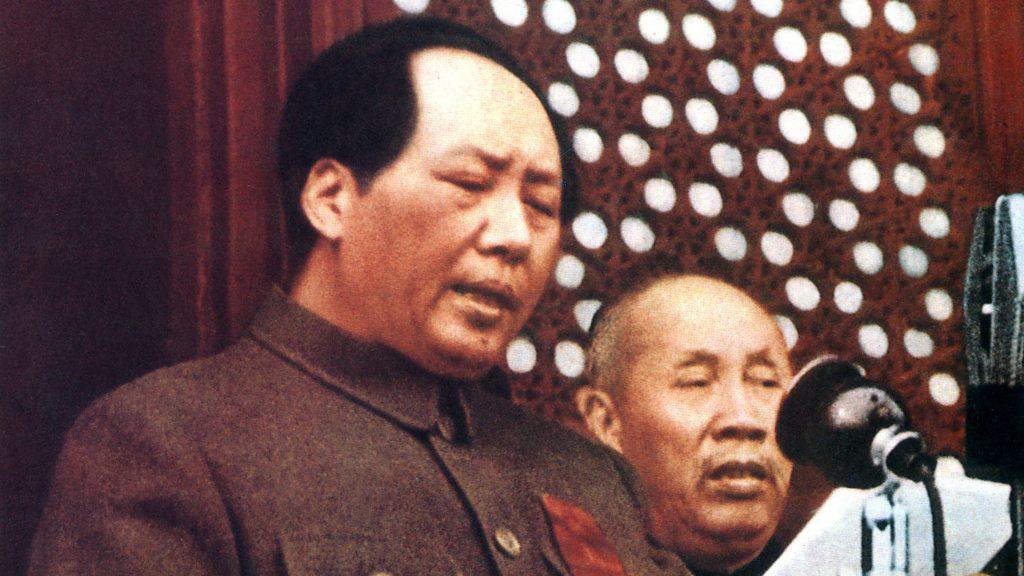

Mao Zedong announces the creation of the People's Republic of China

For many years after the founding of the People's Republic in 1949, Chinese life was tumultuous and unpredictable.

Shortly after my grandparents decided to stay, waves of political upheaval arrived. His background became a problem. Like many in Communist China who had been associated with the Nationalists, he was paraded around when other families gathered together to celebrate the lunar New Year.

And the family was poor. One day my grandmother cooked an egg and cut it into four pieces to feed their four hungry teenage sons. My father told me this story many years ago, and he had tears in his eyes.

But my grandfather never gave up on the dream of a better life: one where the family would live peaceably and where his children would have the means to better themselves.

He told his four sons that things do change, but learning a useful skill would help them survive. So my father and his three brothers, who were prohibited from entering high school because they were from the "wrong background", all learned to be carpenters - hence the three-story house I grew up in.

When China changed course

Things did begin to slowly change on the mainland towards the end of the 1970s. Chairman Mao had died in 1976; his Cultural Revolution ebbed away - and in 1979 the United States embraced the People's Republic diplomatically.

To historians, this move altered the trajectory of the Cold War; to those barely stepping out of Mao's shadow, it opened their eyes and brought them a glimmer of hope.

"We immediately recognised the significance of this" - the moment when Nixon met Mao

Ordinary people may not think in terms of geopolitics or great power rivalry. But they know the thaw between Washington and Beijing helped China move forward and showed its people an alternative way of life.

In the 1990s when some Chinese people began to emigrate to America, the national TV sensation was a long series called A Beijing Native in New York. It began with this line: "If you love him, send him to New York, for it's heaven. If you hate him, send him to New York, too, for it's hell."

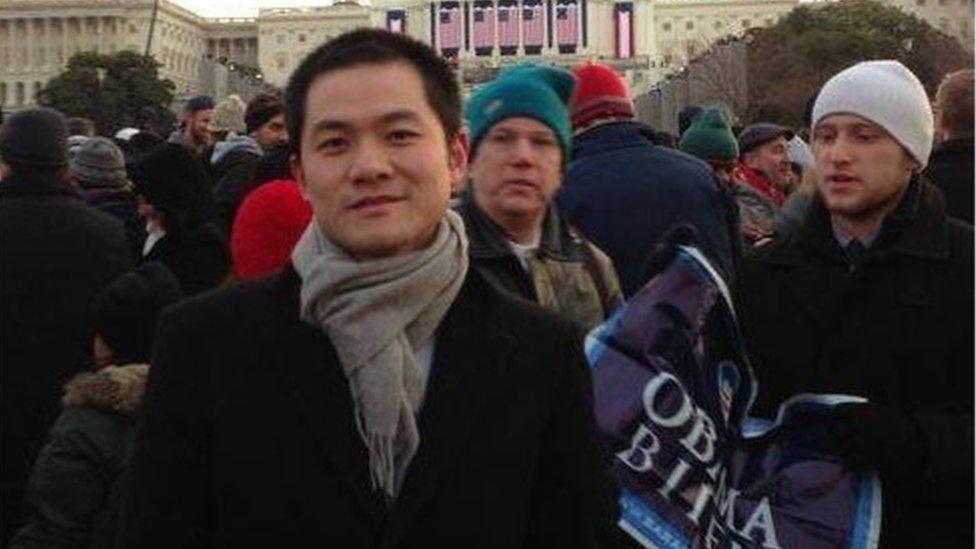

Until recently, many Chinese people found America fascinating, despite its contradictions. So in 2012 when I told grandfather that I was going to live and work there as a reporter, he put his thumbs up, his eyes beaming with pride.

Vincent as a Washington correspondent covering the Obama-Biden inauguration in 2013

America today is different from what it was even eight years ago. The deterioration of its relationship with China under the Trump administration has often made global headlines in the past four years.

Some of my friends in the US now worry that their upbringing in China might one day land them in trouble.

To Robert Daly, who was in his 20s when he played one of the main roles in A Beijing Native in New York, the change in Chinese attitudes toward the US in the last few years is telling.

"In the early years of US-China diplomatic relations, there was tremendous goodwill on both sides. The Chinese were full of excitement after a long period of alienation; they were curious about the outside world, in particular about the United States," Daly told me from Washington, where he now directs the Woodrow Wilson Centre's Kissinger Institute on China and the United States, external.

Robert Daly was the only American actor in A Beijing Native in New York in the early 1990s

These days, Americans have less favourable views of China, external. But the feeling on the other side of the Pacific is mutual.

As outgoing President Donald Trump's strategists describe US-China engagement as a failure and advocate Washington "decouple" with Beijing, many Chinese, according to the China Data Lab at the University of California San Diego's School of Global Policy and Strategy, external, also express disapproval of America.

"[And] Covid-19 made the situation worse," Professor Lei Guang, external, who led the study, tells me. "President Trump's insistence on calling Covid the 'China virus' incensed the Chinese public, whose views are shaped by heavy censorship and a closed media environment.

"Trump's poor handling of the pandemic affected the standing of the United States, once seen as the almighty superpower, among the Chinese public as well. Until and unless the two countries mend their diplomatic relationship, the Chinese public's views of the US are unlikely to improve," Prof Guang says.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

President-elect Joe Biden will soon lay out his China policy as he takes over in the White House on 20 January. Some analysts expect an improvement in bilateral relations.

But Robert Daly disagrees. "There is no going back," he says. "US-China relations are going to remain fundamentally contentious - probably for decades to come."

I never had a chance to speak about the shift in the mood in Washington today with my grandfather.

But I don't think he would agree with the talk of decoupling and the end of engagement, for it was America's closer relationship with China that opened the door to millions of his countrymen and women.

And his proud grandson was one of them.

You can listen to Vincent's radio dispatch on the life of his grandfather from From Our Own Correspondent on BBC Sounds.

You may also be interested in:

What was China's Cultural Revolution?

Related topics

- Published18 December 2018

- Published30 September 2019

- Published14 December 2017

- Published16 May 2016