Lelush: How a sulky Russian model became China's slacker icon

- Published

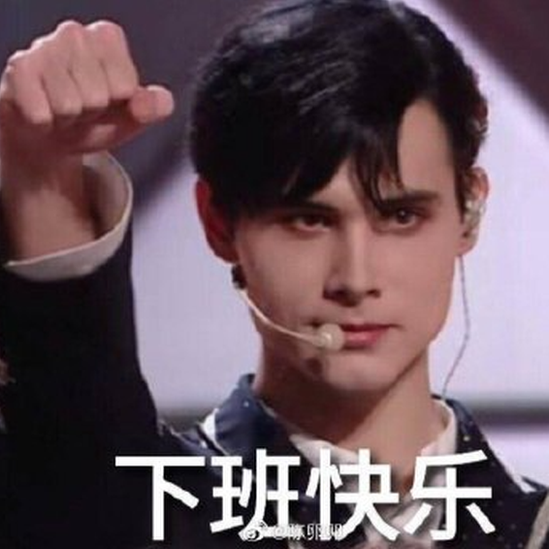

Lelush's deadpan expressions have since graced many a meme in China

Being kicked out of a reality TV show might not be something to celebrate, but for one Russian man it was a dream come true - and the latest twist in his unlikely journey to becoming an icon for Chinese slackers.

Vladislav Ivanov - better known by his stage name Lelush - is one of the hottest stars of the Chinese internet at the moment.

Hashtags and memes featuring his sulky, bored face dominate social media, as thousands of youths have embraced the 27-year-old model as the new symbol of "sang wenhua", a youth sub-culture centred on pessimism and apathy.

It all began when he made the worst - but also possibly the best - decision of his life.

Trapped in a TV show

Earlier this year, Lelush was asked to give Chinese lessons to two Japanese contestants in Chuang 2021, a reality TV competition aimed at creating China's next boy band sensation.

The Russian model, who is fluent in the language after living in China for several years, agreed.

But Lelush's good looks did not escape the notice of the show's producers. Days before the show began in early February, they asked him: would he like to join as well?

Figuring he had nothing to lose - in later interviews he said he "felt like trying out a new life" - Lelush said yes.

Like other contestants, Lelush had to wear an official uniform for the show

As one of the show's 90 contestants, he was promptly enrolled in boy band boot camp - hours upon hours of singing and dance classes, with his every move broadcast to the rest of China.

According to reports, contestants could not leave their accommodation on the island of Hainan, and were cut off from the online world. They had no access to computers and even had to hand over their mobile phones.

This was clearly not what Lelush had expected - and he was brutally honest about it.

"I don't want to dance. I'm also not suitable for a boy band too. So I'm really very tired. I want to go home this month," he bluntly stated in one interview., external

But there was not much of a way out - the contract contestants had signed reportedly carried a hefty fine if they decided to leave. The only way they could escape was if they got voted out.

And so, Lelush decided to be the worst contestant ever on Chuang 2021.

Week after week he slept in late, sulked through his interviews, and listlessly took part in classes, taking every opportunity to slack off during rehearsals.

For his stage performances, while other contestants crooned romantic ballads or performed energetic dance numbers, he mumbled his way through a mournful Russian rap - twice.

Allow YouTube content?

This article contains content provided by Google YouTube. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Google’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

To his exasperation, the audience loved it all - his dourness, his deadpan answers, his low-key frustration at being trapped in a 21st Century Kafkaesque nightmare.

The show's directors, sensing he was ratings gold, played up his reluctance in their edits of episodes. Meanwhile his ever-growing fanbase - who christened themselves "sun si", or "mean fans" - voted for him repeatedly to ensure he remained in the show for weeks, grimacing and gyrating for their viewing pleasure.

One meme read: "Lelush: Get me off this island."; "Mean Fans: Okay! We'll definitely get you in the top five!"

Thus, like an unwilling phoenix half-heartedly flapping out of the ashes, a new star of Chinese slackerdom was born.

Disillusioned rejection

Expressed largely in online memes and jokes - but also now a marketing trend that sells bubble tea, among other things, external - China's "sang wenhua", or "sang" culture, is a movement that ironically celebrates aimlessness and hopelessness. Its name uses a Chinese character that means "loss".

Previous poster boys have included a popular Chinese actor slumped on a sofa, Pepe the Frog (which, unlike elsewhere, is not considered a right-wing symbol in China), Bojack Horseman, and even a lazy Japanese fried egg mascot.

Slouching its way into the public eye about five years ago, it emerged as a disillusioned rejection of China's achievement-oriented culture epitomised in recent years by the Chinese Communist Party's "positive energy" propaganda slogan., external

Faced with worse inequality and unemployment rates compared to previous generations, and rising housing prices in major cities, many youths have found traditional goals such as getting a job and owning a home becoming increasingly unattainable, say experts.

"Much of China has been lifted out of poverty, but youths' desires to fulfill their dreams, that has become increasingly difficult because there's a greater level of social inequality than seen in their parents and grandparents' generations," says Dr K Cohen Tan, associate professor of digital media and cultural studies at University of Nottingham Ningbo China.

"So it's a huge barrier, but at the same time there are still these expectations [to do well."

"Sang" culture thus represents "an illusory utopia where youths can escape from their exhausting, anxiety-ridden everyday lives", says Dr Hui Faye Xiao, associate professor of modern Chinese literature and culture at the University of Kansas.

Lelush's slacker ethos was particularly relevant for a 2021 Chinese audience, whose "sense of powerlessness has been further heightened during the pandemic", Dr Xiao tells the BBC.

Lelush memes have flourished online, while phrases that he often used on the show - "I'm really tired", "when do we finish class" and "I want to go on leave" - have gone viral.

"So tired"

"Save me"

"Happy to knock off work"

In particular, Dr Tan says, Lelush's frustration about having to work hard on the show mirrored many young people's "sense of defeatism" about China's notorious gruelling "996" work culture - so-called for people who work from nine in the morning to nine in the evening, six days a week.

"This sense of entrapment, of helplessness, is what many young people feel - they work very long hours, but are unable to quit even though they would love to," he tells the BBC.

One turning point was when Lelush was graded F for a lacklustre performance, to which he declared: "F is for freedom."

In an instant, he turned a prospect that many Chinese youths dread - getting a bad grade - into an ironic rallying cry embodying "the desire to be liberated from the pressures that many face themselves", says Dr Tan.

'If you love me, don't support me'

But perhaps the only person who hated Lelush's journey to become a slacker icon was Lelush himself.

"If you love me, please don't support me," he pleaded with fans, in video after video filmed for the show.

His wish was finally granted late two weekends ago when, to his utter relief, he finally got voted out of Chuang 2021 after three long months on the show.

Footage of that episode showed him waving onstage along with other contestants, then dashing headlong towards the exit, with show staff in hot pursuit., external

Shortly afterwards a new post popped up on his official Weibo account, though it's not known if it was penned by him or the show's producers: "Thank you everyone for your support, I finally get to knock off work."

The post was accompanied by a Lelush meme of him smiling, captioned: "Super happy."

Since leaving the show he has kept a low profile, saying little to the media. He did not respond to the BBC's requests for an interview.

He refused to tell Chinese news outlets what his next steps were, only cryptically saying: "I don't want to constrain my freedom."

But there are signs that he intends to cash in on his newfound fame. Over the weekend he plugged a mobile phone game on his Weibo account - with the ironic hashtag "Lelush working on Labour Day" - and has been offered a deal with another game developer.

And of course, China's newly-crowned slacker god appears to be enjoying a well-deserved break.

This week Lelush posted on Instagram a photo of himself lounging in bed, saying in a mixture of English, Mandarin and Russian: "Finally resting and relaxing."

Allow Instagram content?

This article contains content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Instagram cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Additional reporting by Waiyee Yip.

You might also be interested in:

Inside China's child pop star factory

Related topics

- Published27 December 2019

- Published12 January 2021

- Published15 April 2019