Theatrics or threat: How to handle China's Communist party at 100

- Published

As China's ruling Communist Party celebrates its auspicious anniversary, the debate is intensifying over how to deal with the renewed prominence of authoritarian values at the heart of the world's second largest economy.

For the Communist Party, this is meant to be a moment for basking in the warm adulation of the masses, not for talk of a new Cold War.

And Max Baucus, the former US Democratic Party Senator who served as US ambassador to China from 2014 to 2017, finds himself in agreement.

"The vast bulk of people in China… care very little about a change in the party because they're more concerned about their own lives," he says.

"Living standards in China have risen dramatically in the last 20 years and they're very happy about that."

China's changes: Yan Zhigang has spent four decades photographing the streets, and the people, of China

What to do, if anything, about the Communist Party's tightening grip on power, the growing personality cult of its leader Xi Jinping, and the draconian direction of its domestic policies is one of the defining international policy debates of our time.

And while it divides opinion in Washington and Europe - between those arguing for ideological confrontation and those, like Mr Baucus, for continued strategic engagement - such differences may well be much harder to glean inside China.

But they're there.

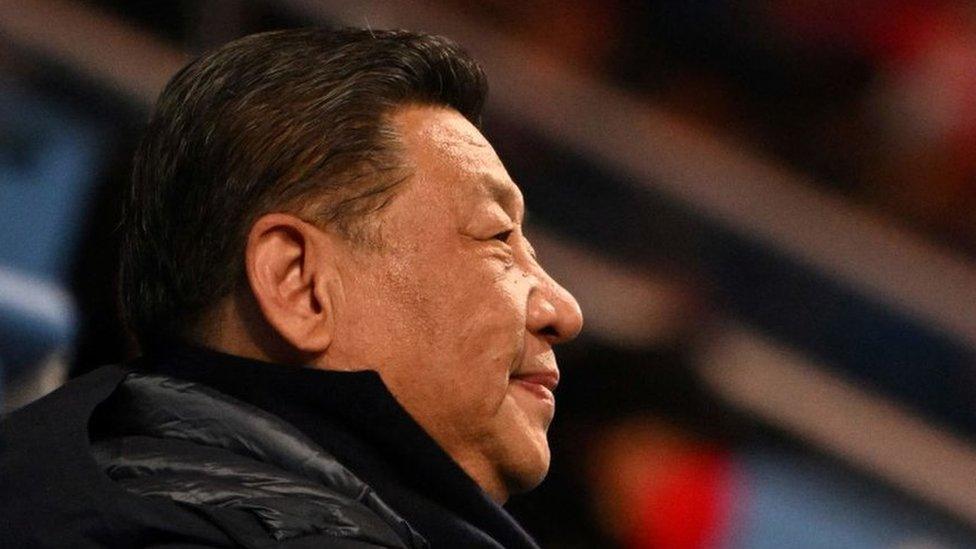

Cai Xia is a retired professor from Beijing's elite Central Party School, now in effective exile

Cai Xia is a retired professor from Beijing's elite Central Party School, who spent her life working with and training senior officials until her growing doubts and criticisms forced her into effective exile last year.

She doesn't buy the idea that the Chinese people don't want political change, nor the notion that engagement with the Communist Party is better than the alternative.

"It's not too late to change China from an autocratic system to a democratic system," she says.

"The earlier the better, for China and the whole world. Even though Xi Jinping calls for a 'shared future for all mankind', he has already launched the Cold War and it never stops."

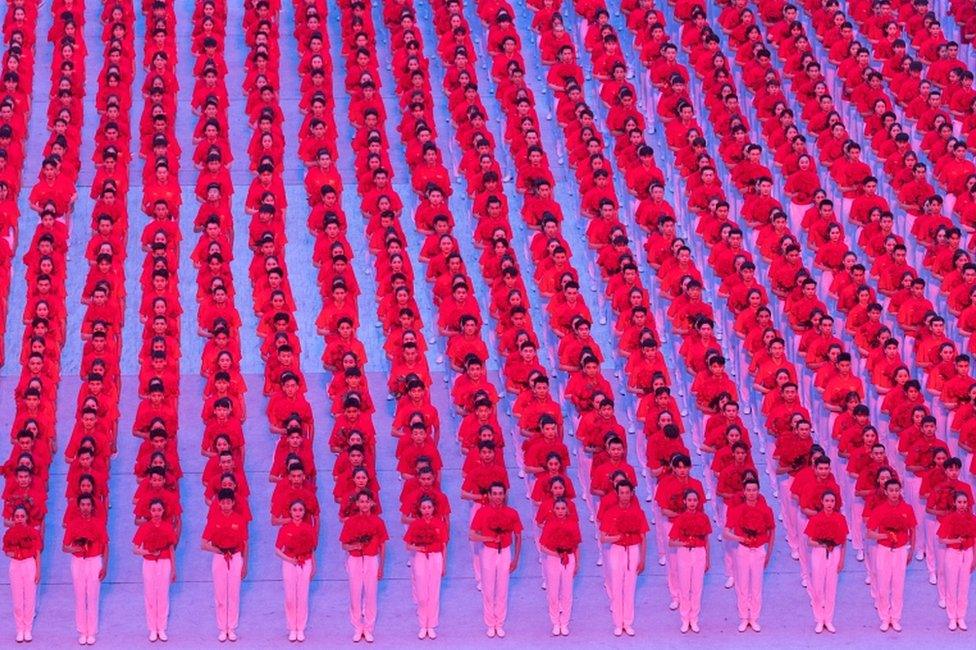

Propaganda for the Chinese Communist Party's 100th birthday

Beijing's party for its party - involving large quantities of pomp, pageantry and pyrotechnics - brings into sharp relief the prospect of an ever-rising, ever more prosperous, capitalist China with a rigid Leninist system at its heart.

The question is whether the celebrations are just another piece of theatre - a distraction from the real story of the undoubted personal enrichment and increasing lifestyle choices of millions of ordinary Chinese people.

Or whether they're a troubling reminder that all this prosperity and power are held, ever more firmly, in the hands of a one-party state, willing to use them, not just against its own people, but the rest of the world.

Max Baucus served as US ambassador to China from 2014 to 2017

Max Baucus belongs to a school of thought that has dominated US relations with China over the past few decades: the belief that trade and engagement is an end in itself.

Increased Chinese prosperity and an emerging middle class offer the promise, the theory goes, of gradual political reform and, even if that comes agonisingly slowly or not at all, economic integration is at least better than the alternative - confrontation.

He's worried that that consensus now appears to be shifting and that a new, Cold War mentality is taking hold in Washington.

"I think there's too much groupthink in Washington," he says.

"It's very easy for members of Congress, the president, to bash China politically. It's so bipartisan, it's a big problem.

"We've got to work with China," he adds. "The people of China and America are basically the same, they care about their families, about putting food on the table. And I think policymakers should keep that in mind."

China is celebrating the 100th anniversary of the founding of its ruling Communist Party with events big and small

But Cai Xia disagrees.

Expelled from the party while on sabbatical in the US and now unable to return to China out of fear for her own safety, she thinks it's folly to focus on the positives of economic change while ignoring the politics of the party.

"Western politicians and scholars lack a real understanding of China," she says.

"After China opened up to the world, it hoped to use the global system to strengthen its own power, that was the real intention. That's why it shows a friendly and open manner to the world; but, in fact, the party's Cold War mentality has never changed."

The West, she believes, fails to see that it is already locked into an ideological confrontation, whether it wants one or not.

Deng Yuwen is the former editor of an influential Communist Party newspaper, the Study Times, another insider who is also now living in exile, unable to return to China for fear of arrest following his own published criticisms of the system.

He has some sympathy for the view that China's rapidly changing economy might once have held out the prospect of political reform.

"Ten years ago, the party was gradually fading into the background," he says.

"That's what Xi Jinping wasn't satisfied with, he considered it dangerous; so now using his own words - 'from North, South, East, West and centre' - the Party is comprehensively controlling the country."

Mr Deng believes that under this renewed dominance of the party, China has taken a great leap backwards.

It has become increasingly oppressive at home - with its giant re-education camps in Xinjiang and the mass arrests in Hong Kong - as well as increasingly ready to assert its authoritarian values on the global stage.

"Now China is powerful, it's doing business with the world, so other countries need to be mindful of China's emotions and its practices," he says.

"This will gradually exert an influence on those countries. By accepting China's system and its logic, the West may gradually change, this could be a danger for the West."

Prof Cai goes even further, arguing that this is now a deliberate part of the strategy; if the forces of globalisation have failed to reform the Communist Party, it is all too ready to use those same forces to actively foist its values on the West.

"China has been preventing peaceful evolution, in which Western values might enter China and affect the Chinese public, and preventing it by all methods," she says.

"While at the same time, China is using the Western world's freedom of speech and freedom of the press to export its information, illusions and propaganda to other countries."

As if by way of illustration, the BBC contacted more than a dozen academics at a number of Chinese universities, including Prof Cai's old party school, in the hope of speaking to them about the party, its place in Chinese society and the significance of the anniversary.

So tight are the controls on information within China, especially around important occasions like this one, that none of them were available or willing to speak.

The ministry of foreign affairs did not respond to several requests to help source a suitable expert on party matters, despite having offered to assist.

Centenary events were planned meticulously

Given its ripe old age and its central role in Chinese history, those who still support the idea of engagement with the Chinese Communist Party believe that you can't simply wish it out of existence.

"I believe we should continue to advocate for our Western liberal values," former ambassador Baucus says. "They're better, no question about it.

"Having said that, China has grown in a different way and they're going to continue to grow in a different way… and if we can't influence them towards a more democratic form of government, we have to accept that and deal with it."

When I ask about Xinjiang and Hong Kong, he tells me that, while the party is determined not to relinquish political control, he believes there are limits.

"They calibrate their control, pretty well. That is, if they're too controlling, too repressive, the people tend to react against it. On the other hand, they can be repressive up to a point."

But Prof Cai, who knows the party from the inside out, argues that there are now, in reality, few internal limits on its power and it is time for a different model, one that is far more cautious about engagement and trade as ends in their own right.

"I hope the Western politicians and the world will see China's situation and take action. This totalitarian system - any totalitarian system - will not last forever. It will change one day and we should really help that to progress."

Does she have any positive words for the party she spent so many years working for on the occasion of its 100th birthday?

"In China, 100 years old also means a person has lived long and it is time to think of death," she says.

"If I have to say anything positive, I hope that on this anniversary, the Communist Party reviews the serious mistakes of its policy making which have made the Chinese people suffer and pay such a huge price. It should do redemption, not celebration."

Related topics

- Published1 July 2021

- Published27 June 2021

- Published30 June 2021

- Published10 October 2022