Ukraine invasion: Can China do more to stop Russia's war in Ukraine?

- Published

China has always said repeatedly that it does not interfere in the internal affairs of others

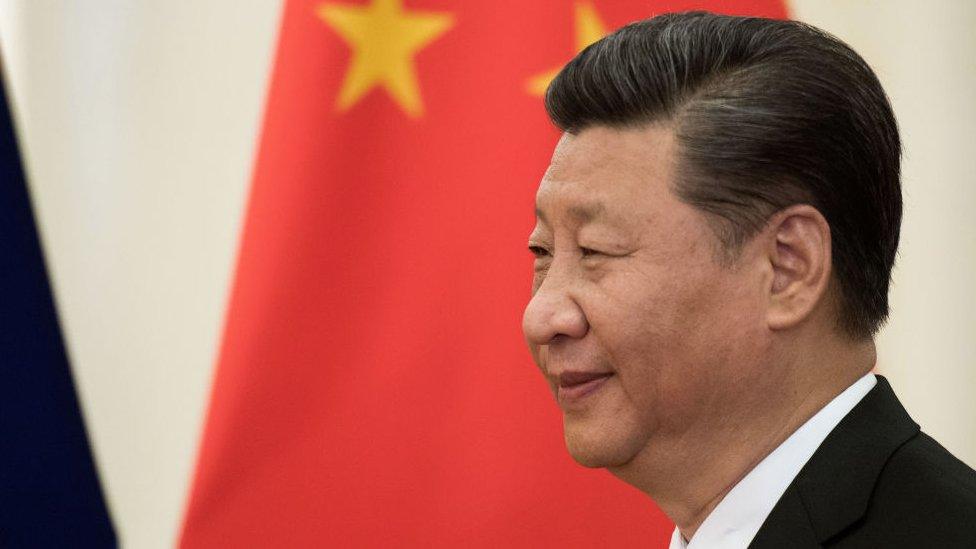

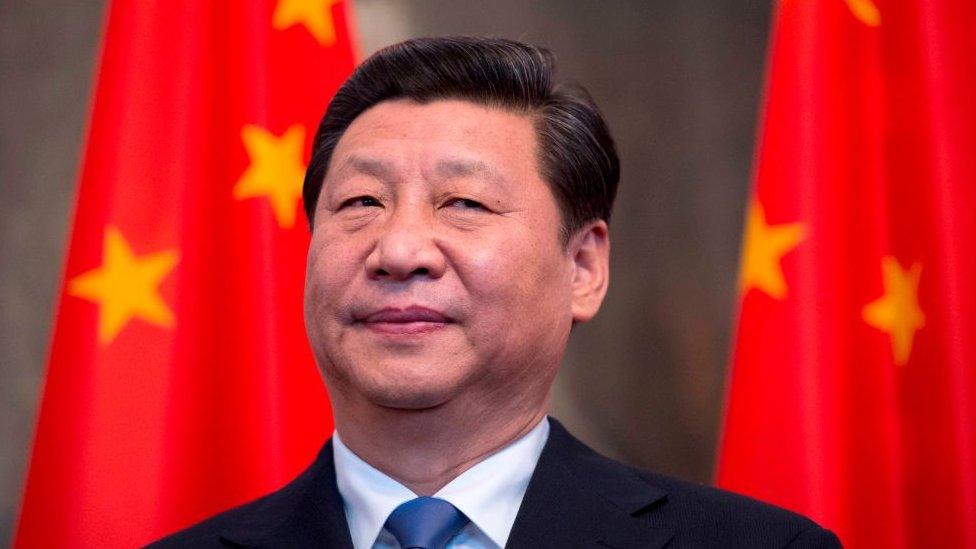

A month ago, Chinese leader Xi Jinping declared there was "no limit" to Beijing's newly strengthened relationship with Russia.

He and his Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin had met face-to-face in Beijing, culminating in a joint document - and then they went off to see the opening of the Winter Olympic Games. Days after the Games ended, Russia invaded Ukraine.

China's government has neither condemned nor condoned the attack and has even refrained from calling it an "invasion" in the first place. It has always said that it does not interfere in the internal affairs of others, a core principle of its foreign policy.

But earlier this week, China's Foreign Minister Wang Yi signalled that it was ready to play a role in mediating a ceasefire. State media here reported that Mr Wang "reaffirmed China's unwavering support for Ukraine's sovereignty" and assured his counterpart of China's readiness to make every effort to end the war... through diplomacy".

China's government also recently expressed "regret" about the military action, saying it was extremely concerned about the harm to civilians.

China has also done one other thing of note. Alongside India, it was one of 34 nations that abstained from voting on a United Nations resolution condemning Russia's invasion - something analysts say has come as a surprise. Many had expected China to vote alongside Russia.

So, is it a sign of a shift in China's policy?

It is more likely a sign that China is trying to strike a balance between the principle of respecting Ukraine's sovereignty while recognising what it describes as the "legitimate security concerns" of Russia.

If you look back to the 5,000-word document signed off by Presidents Xi and Putin when they declared their deepening, unlimited alliance you'll see that objection to Nato expansion unites them, though the agreement covers multiple areas of common ground and planned co-operation; in space, in the Arctic, on Covid-19 vaccines.

It is their shared vision of a future in which China and Russia work much more closely, for mutual benefit.

Fundamental differences - and similarities

The other key context to why China might stand fast in its support for Russia and Vladimir Putin - or its lack of condemnation, depending on how you see it - is Taiwan.

The self-governing island, regarded as a rogue province by Beijing, is a place that President Xi wants to see "reunited" with his motherland. Were Mr Xi to do that by military force China would likely face a similar - or likely more serious - reaction from the US and its allies; condemnation, heightened sanctions, cultural exclusion.

Taiwan is not Ukraine. If nothing else, the legal status of the two places is different.

But in acknowledging what it calls Russia's "legitimate security concerns" and caveating the core principle of respecting sovereignty because of "complex and unique historical context", China's leader likely sees a future in which he can seek to justify to the world an "invasion" of Taiwan, and expect Russia's reciprocal support.

And then there's the personal relationship between Mr Xi and Mr Putin. The two have met in person nearly 40 times now.

When he arrived for the Winter Games last month, Russia's president was the most prominent leader by far to come to China since Covid-19 began.

Both are autocratic leaders who share an ambition to deepen the ties and allegiance between their people and their "motherland". Xi Jinping sees a future where China - a vast economy - is more-self-reliant, decoupled to an extent from some of the global ties it has benefitted from.

But the new "no limit" partnership with Russia may not mean an inevitable re-alignment away from the US, its allies and the established world order.

It is, after all, an order in which China has sought to do more in recent years; on climate change, on peace keeping.

And there are also the politics to consider. Not electoral politics, but the politics of association with a warring nation.

China censors much of what its people can see and read but the severity of the war, which - more than any other conventional conflict - is being documented in often horrific detail, by the minute, on social media, may become an important factor in Beijing's calculations over its stance on Russia.

Xi Jinping and the other senior leaders around him may conclude that there is, in fact, a limit to the relationship, and they need to step back - or step up and try to play the role of mediator with Moscow. A role that it told Ukraine it was prepared to take on, but which it has yet to show any sign of starting.

Related topics

- Published28 February 2022

- Published24 February 2023