China Covid: The politics driving the hellish lockdowns

- Published

The world has largely moved on from Covid - except for China, where towns and cities are still shut down overnight.

And that's unlikely to change soon, judging by President Xi Jinping's opening speech at the Communist Party Congress on Sunday. China - and even the world - was hoping for a hint of relaxation. But Mr Xi, who is set to be handed a historic third term to lead the Party, said that the government would not "waver" in its commitment to record zero cases.

Driven by Mr Xi's approval, China's lockdowns have been incessant, unpredictable and hellish by most accounts. They have sparked food shortages, crippled healthcare access, hit the economy hard and even spurred rare signs of protest.

But Beijing has clung to zero-Covid, which has come to define Mr Xi's rule and the authoritarian bureaucracy at his disposal like almost no other policy.

Confuse or convince?

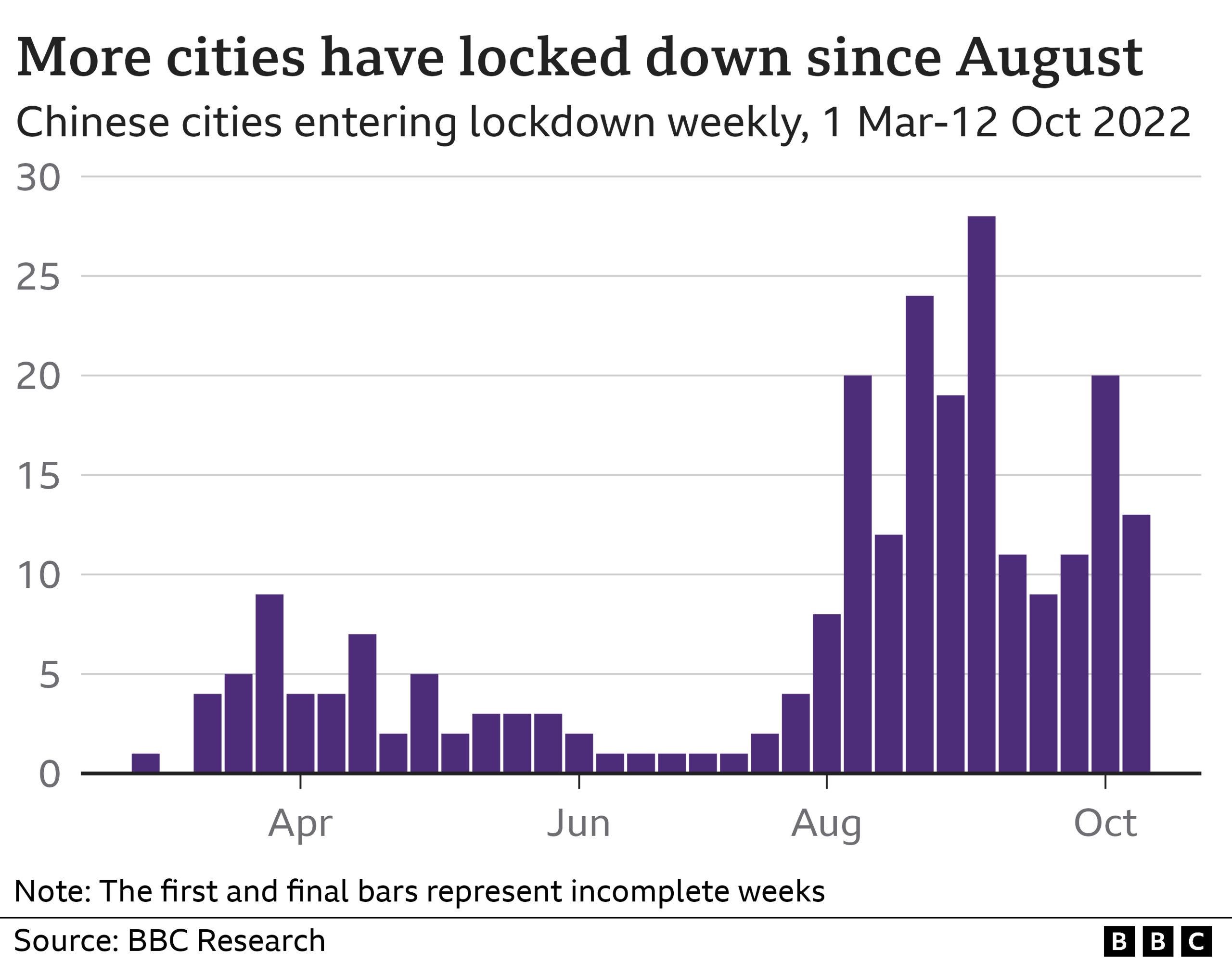

The BBC found that since March, China has partially or fully locked down 152 prefecture-level cities, affecting a population of more than 280 million. But 114 of those have been locked down just since August, as the Party Congress approached.

Your device may not support this visualisation

Beijing is the only major city to have avoided a full lockdown so far. Residents half-jokingly observe that the capital has managed this by locking down the rest of the country when needed. However on Thursday some housing estates and shopping centres in Beijing were being locked down after a steep rise in cases.

BBC gathered data starting in March because that's when China's fourth phase of Covid control measures kicked off - comparing lockdowns across phases is harder because official language changes, skewing definitions and therefore, the corresponding data.

And China's bureaucrats have certainly found inventive new ways to describe lockdowns. The measures had become so controversial and dreaded that confusing official-speak was one way to make them more palatable.

So they used phrases like "stasis management", "at-home stillness" or to be clearer, "stillness throughout the whole region" or "stop all unnecessary movement".

Then came "temporary societal control", which authorities said was not a "lockdown" but reduced movement that somehow would not affect the "normal order of production and life", external. And yet "the public was asked not to go out unless necessary".

"Enclosed management" was another new phrase invented in the southern province of Guangdong. It means that the village, district or residential compound is enclosed, with checkpoints at entrances and exits. People and vehicles are allowed to enter and leave with passes. People who do not live or work in the enclosed area are not allowed to enter. But, residents were told, it's not a lockdown.

When track-and-trace methods started to grate, eager officials came up with an alternative: "temporal and spatial overlapper". The sci-fi-inspired phrase refers to someone whose location, tracked by their phone, has overlapped in time and space with someone else who is Covid-positive.

Rather than tell people not to visit their hometowns during this year's Spring Festival, the governor in Dancheng County in central Henan province warned them that "those who come home with malicious intent will first be quarantined, then be detained".

Now China is in what Beijing calls the "scientific and precise dynamic zero" phase, whose meaning no-one seems to be sure about. It's meant to be one step up from the earlier "dynamic zero" policy.

Dynamic because the idea is that it's not just about locking down entire cities and towns but about responding more dynamically depending on what the situation requires. But on the ground, it just looks and feels like a series of endless lockdowns.

The year began with the tourist hub of Xi'an, home to 13 million, being shut down for a month. Then in March, a lockdown was announced in Shanghai. It was meant to last less than a week, but its 25 million residents stayed home for two months. In September, residents in locked down Chengdu found themselves trapped in their apartments during an earthquake. Elsewhere, rescue workers were required to do a Covid test before they could save anyone.

Chengdu was among several cities where a lockdown caused food shortages

That same month, hundreds of thousands of people in two cities in Shanxi faced a lockdown without a single case being reported: officials said it was to "contain the risk from outside". A local party leader vowed to protect the area "to welcome the 20th Party Congress with excellent results".

Pleasing Mr Xi

Beijing has repeatedly insisted that "dynamic zero" means local authorities must not resort to a "one size fits all" approach of full lockdowns and mass testing.

But there appears to be a discrepancy between that diktat and what's actually happening in towns and cities across China. Several lockdowns announced by local officials were, in fact, missing from Beijing's daily announcements in March and April - including one in Shenzhen which confined 17 million to their homes for a week.

It's possible central government officials did not want to encourage total lockdowns by drawing attention to them, while local officials preferred to use them to control outbreaks swiftly.

Experts also say China's bureaucracy is far more centralised under Mr Xi - it's a reversal of the decentralisation that began after China introduced economic reforms. What that means now is that bureaucrats enforce Mr Xi's signature policies with zeal.

"Xi's appetite for adaptive governance and his relationship with local authorities varies by issue areas," says Yuen Yuen Ang, a political science associate professor at the University of Michigan.

"On his signature policies, those he declared as having no room for 'wavering', there is little or no leeway for local governments to make adjustments. Indeed, to survive and get ahead, they must over-implement Xi's personal edicts with gusto, even if the net result is damaging."

From April onwards, the lockdown tallies in Beijing's announcements matched those in local notices - around the same time Mr Xi reaffirmed his support for sticking to a zero-Covid approach. As the year wore on, more cities stopped meticulous track-and-trace and entered full lockdowns even if only a handful of cases were reported.

Local officials are driven by both fear of punishment and an urge to display loyalty to Mr Xi, says Wu Guoguang, a senior China scholar at Stanford University. He was once a member of the Chinese Communist Party's policy group on political reform.

When it comes to proving their loyalty, Mr Wu adds: "There is an undeclared competition among local leaders, which provides a huge momentum to their seemingly unreasonable measures."

It's all political

And, experts say, it's no coincidence that the lockdowns started to spread as the congress approached.

"Covid is political in China," says William Hurst, professor of Chinese development at Cambridge University.

The carefully scripted once-in-five-years party congress carries special import this year - if it goes according to Mr Xi's plan, he becomes the first leader since the first Communist-era leader Mao Zedong to serve as party boss for a third term. And nothing can ruin the party quite like a Covid outbreak - especially since Mr Xi and his bureaucrats insist "dynamic zero" is a success that has been saving lives.

It has indeed prevented a major outbreak like the one in Shanghai earlier this year, says Benjamin Cowling, chair of epidemiology at the University of Hong Kong. "What is less certain is whether the cost is justified, and whether this approach is going to be sustainable given its enormous economic costs," he adds.

Locking down millions of people may be helping keep national case counts low, but the decision to do so even as the rest of the world opens up also shows how poorly prepared China is for a post-Covid world.

Public health experts argue that if zero-Covid was indeed about saving lives, Beijing would have implemented a more vigorous vaccine policy like other countries. But China has refused to import vaccines despite evidence that its homemade jabs haven't proved as effective. And unvaccinated elderly people, who Beijing says it's trying to protect with zero-Covid, have died from the virus.

But what zero-Covid has done, experts say, is project a veneer of control and stability as the year's biggest political event unfolds.

Prof Hurst expects the intermittent lockdowns to last at least until March next year, when China's equivalent of parliament convenes to choose Mr Xi as president for a third time.

"Lockdowns prevent Covid outbreaks from spreading," Prof Hurst adds. "But they also exert incredibly strict social control."

- Published17 October 2022