How China's Covid protests are being silenced

- Published

Unable to speak out, many are finding novel ways of getting their voices heard. But the censors are catching up

China's censorship machine is going to great lengths to prevent people seeing scenes of protest in multiple Chinese cities.

Demonstrations erupted across the country at the weekend in response to strict anti-Covid measures that have been in place for three years.

An ever-growing list of words that reference the protests are being censored, and attempts are being made to deflect the narrative on both domestic and overseas platforms.

The rare widespread protests began after ten people died last week in a fire in the city of Urumqi. Many believe residents could not escape the blaze because of Covid restrictions, but authorities have disputed this.

As is generally the case with protests in China - even small-scale ones - Chinese media have made no mention of them. Reports on the country's Covid outbreak over the last few days have been muted, with outlets choosing to focus on upbeat stories like China's latest achievements in space.

The scenes of protest posted on platforms like Twitter, and widely shared internationally, are being ignored by state media outlets.

A growing list of banned words

To stop people talking about the latest anti-Covid protests, the words "Shanghai" and "Urumqi" - cities where residents have protested - have been added to a list of censored search terms by platforms like Weibo. Whereas before they showed tens of millions of results on the Chinese social media platform, now they only show hundreds.

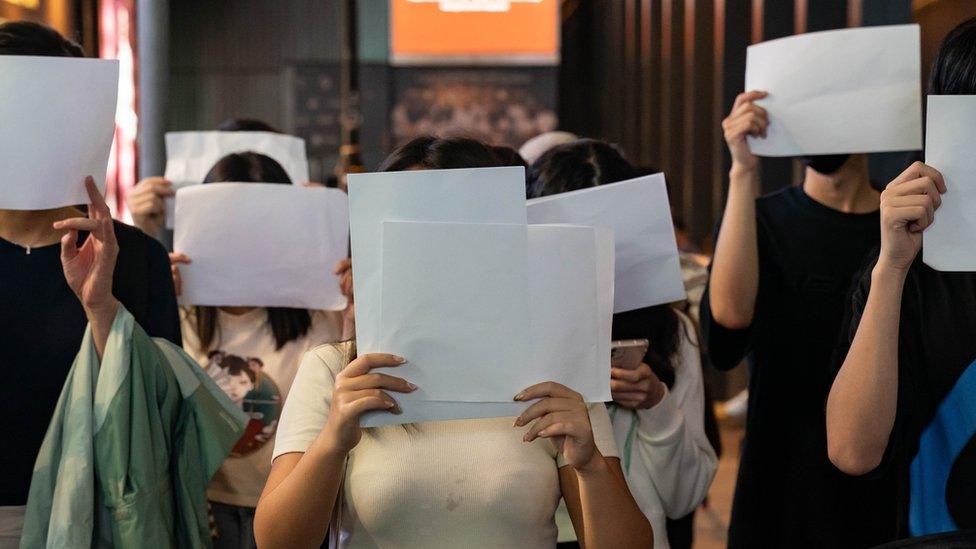

In an attempt to bypass the censorship, people began using terms like "white paper" and "A4" - a reference to the pieces of bland paper that have become a symbol of the protests. But now even these have become censored search terms on Weibo.

Far from being deterred, creative social media users are finding new ways to show their solidarity with protestors. They discuss "A3" paper instead, and have referenced historic social media trends that mention paper, like the "A4 skinny waist challenge".

One of the most common ways Chinese social media users get messages out is by posting on foreign social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook.

These are blocked in mainland China and are only accessible with a piece of software known as a VPN. But some nevertheless have taken to these platforms to highlight demonstrations that have taken place.

Overseas Chinese have also staged protests outside Chinese embassies, lighting candles and holding blank pieces of paper.

These are scenes that the Communist Party government would rather people - especially overseas Chinese - didn't see.

Symbols of the protests - like Urumqi Road - are being held outside overseas embassies in protest

Consequently, there has been a large-scale attempt to flood platforms like Twitter with porn and gambling content using the hashtags #Urumqi and #Shanghai, to stop people searching for footage of the protests.

China has a history of this. During the 2019 Hong Kong protests, Twitter, Facebook and YouTube said they witnessed a co-ordinated attempt by the government to spread disinformation on their channels, and this led to hundreds of accounts and posts being removed.

Foreigners may be blamed

While state media for now appear intent on ignoring the protests, there are early signs that they might shape a narrative where foreigners are to blame for scenes of unrest, should they escalate.

Some are already taking to social media blaming foreigners for instigating the protests.

State media have repeatedly criticised the West for its more lax Covid-19 rules and warned against countries buying into what they see as US rhetoric.

But seeing the rest of the world celebrate in Qatar has fuelled local anger this week. Consequently, China's broadcaster CCTV has moved to avoid showing spectators enjoying matches in its own coverage.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

In addition to this, China introduced eased Covid-19 measures earlier this month. These involved reducing the length of quarantine, making it easier for people to enter the country for short periods of time.

So potentially it will become easier to blame foreigners for the spread of the virus as well. Cases have spiralled to record levels in recent weeks, with more than 40,000 recorded on Monday.

And with no end in sight to China's zero-Covid policy, there is a very realistic possibility of more protests. The number of lockdowns have only increased over the last month, as anybody who tests positive, and their close contacts, are still under orders to quarantine. This hasn't changed since the early stages of the pandemic and people are increasingly frustrated.

It wouldn't be the first time that China had blamed the West for dissent at home. Hong Kong's 2019 protests - the last large-scale demonstrations in China - were blamed on "violent extremists" being influenced by "Western lackeys".

Related topics

- Published28 November 2022

- Published28 November 2022