Grieving a daughter's Covid death in Wuhan - while being surveilled

- Published

A woman - not Yang Min - looks at tombs in Wuhan, China

"The pain lasts for a lifetime. Even healing a little is difficult."

It's been three years since Yang Min's only child, Yuxi, died. The 24-year-old had been diagnosed with breast cancer and was admitted to hospital in mid-January 2020 in Wuhan, the Chinese city where the earliest coronavirus cases were detected.

Wuhan was the first place in China - and the world - to be locked down to stop the spread of Covid. The announcement came in the early hours of 23 January and it sent people, scared and uncertain, fleeing into the night.

That city-wide lockdown, lasting 76 days, would become integral to China's zero-Covid playbook. The country has now scrapped the policy and recently announced that the current wave, driven by a hasty reopening, is drawing to a close.

But as much of China moves on, Ms Yang cannot.

She says she will not rest until she finds "justice" for her daughter. She believes Yuxi would not have died had the government warned the public at the beginning of the pandemic.

Ground zero

When Yuxi went to the hospital in 2020, Wuhan was gearing up for the Chinese New Year celebration - large family dinners, streets filled with shoppers, and the city covered in festive red, customary during the Spring Festival.

In an interview with a book author, Ms Yang said Yuxi's illness didn't dampen the family's holiday spirit because they were confident she would recover. What Ms Yang didn't know was that a new virus was spreading in the city and through its hospitals.

Reports had emerged in December 2019 of a mysterious illness that was believed to be linked to the Huanan Seafood Market. But authorities assured people that there was "no definite evidence" of human-to-human transmission.

Hospitals in Wuhan were overwhelmed during the early days of the pandemic in 2020

Then cases began to rise and by 19 January, when Yuxi developed a fever, Wuhan had recorded nearly 200 cases. On 23 January, when the government locked down the city of 11 million, doctors told Ms Yang that Yuxi would not survive if her fever did not subside.

Over the following days, Yuxi didn't stop coughing. Her breathing became laboured and she vomited blood. Ms Yang, who spent day and night taking care of her, also caught the virus.

On 6 February Yuxi died alone, after spending five days in the ICU. Ms Yang, who had been battling the virus in an isolated ward, was not told until two weeks later.

Ms Yang detailed these events to Murong Xuecun, a well-known writer who recorded her account and others' in Deadly Quiet City: Stories from Wuhan, Covid Ground Zero.

When Ms Yang speaks to the BBC, she says it is too painful to recount - but she talks more about her Yuxi and what life has been like since she died.

"My daughter didn't have any exceptional quality, but she was my daughter, so I miss her. That's what mothers do," she says, crying.

"She was the same as other children. Sometimes she was naughty, sometimes she didn't listen to me, sometimes we argued."

While Ms Yang did not know about the virus at the time, doctors and medical workers in Wuhan suspected something was amiss.

Mr Chen, whose name has been changed to protect his identity, was working at a community health centre when the outbreak began.

He had been in the job for more than a decade and had heard about a new virus from colleagues - well before Dr Li Wenliang, the 34-year-old whistle-blower who died of the disease, was reprimanded by authorities for "spreading rumours".

Mr Chen said they knew it was a coronavirus, but not much beyond that. "We were all in fear because we had no idea," he says. "Now I think about it, it was inconceivable. Nobody could have thought that it would turn out like this."

Louise was shocked by the number of mourners during the first tomb sweeping day since the pandemic

Although the Wuhan lockdown was spun as a success by Beijing, the death toll from the early weeks - before lockdown - remains unknown.

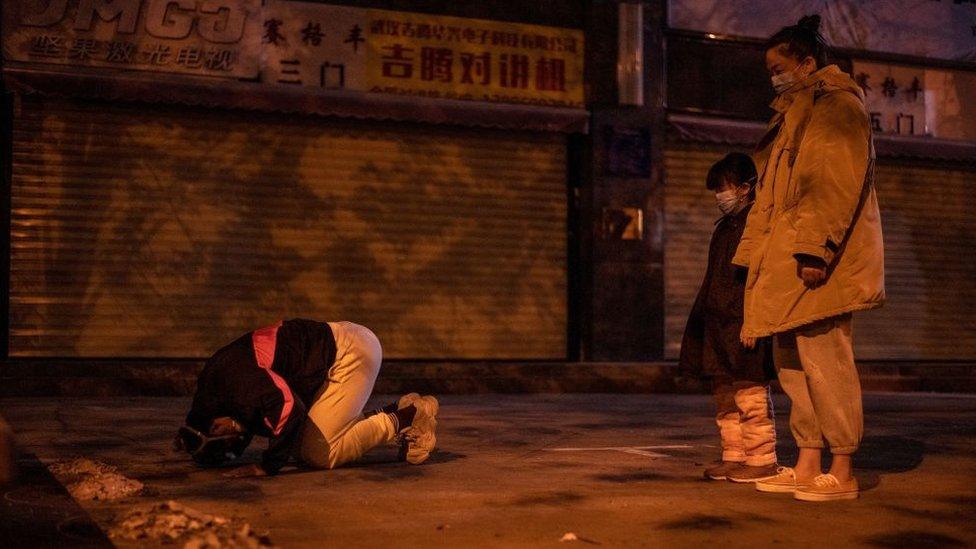

Louise, a tech worker in her late 20s who stayed in Wuhan with her partner through the lockdown, says it was frightening initially, before the cases began to fall: "There were videos showing the bodies on the ground in the hospitals and our food was almost gone... We were afraid that we were being abandoned."

It wasn't until early April - on tomb sweeping day, when Chinese mourn the dead by placing white paper in a circle - that she realised how badly the city had been hit by the virus.

There were circles of white everywhere and chrysanthemums, the preferred choice of flower for mourners, were sold out.

"No-one I know had died of the virus, but I was shocked by the scene," Louise says.

Déjà vu

Ms Yang was one of those mourners three years ago. She says some of her fear and pain was relived this year when China was gripped by a wave of infections as it reopened. This time Ms Yang's mother-in-law, who is in her 80s, was infected.

"I was worried she could die at any moment," she says. "I did everything I didn't do three years ago, everything I had regretted not doing, everything I didn't know then but know now. I was afraid I would put her in harm's way if I was careless with anything... I checked her blood oxygen level every hour."

Ms Yang caught Covid again, but she says she wasn't afraid for herself.

"After what we had experienced, death means little. I don't want to experience the loss of family anymore. If I could, I would die for my mother-in-law."

Her mother-in-law survived - and recovered before the start of the Chinese New Year in late January.

Ms Yang didn't celebrate the Chinese New Year properly

But Ms Yang wasn't in a celebratory mood. She had been under heavy surveillance since speaking to the media about losing her daughter to Covid.

She protested on the streets and has been trying to file a lawsuit against the government. She says she wants "an explanation".

China is a one party-state which does not tolerate protests that challenge the leadership.

The media and the internet are also heavily censored, with many foreign news outlets being banned in the country. People who talk critically about the country to foreign media often face retribution - from warnings to even detention.

With technology, China has also established an extensive surveillance network that monitors mobile device data and tracks movements.

Ms Yang says: "There are people at my door and I am followed everywhere. There is no Spring Festival atmosphere because I am worried I will affect my friends if I go to gatherings. I haven't gone out much."

In Wuhan, on the first day of the Chinese New Year, people visit the homes of those whose relatives have died in the past year, and burn incense for the dead.

"Chrysanthemums were being sold everywhere, especially on Chinese New Year's Eve," she says, adding that it brought back harrowing memories because she had brought two baskets of the flowers for Yuxi.

For Ms Yang, the end of the pandemic does not mean a return to normal life. Not least because there is now a camera at her door, monitoring her every day.

"I am not afraid of them," she says. "I have already lost the most precious thing in life. What else can they take away from me?"

Except for Yang Min, names have been changed to protect identities.

- Published16 January 2023

- Published22 January 2023

- Published7 December 2022

- Published20 June 2020

- Published30 January 2020