Ukraine war: China's claim to neutrality fades with Moscow visit

- Published

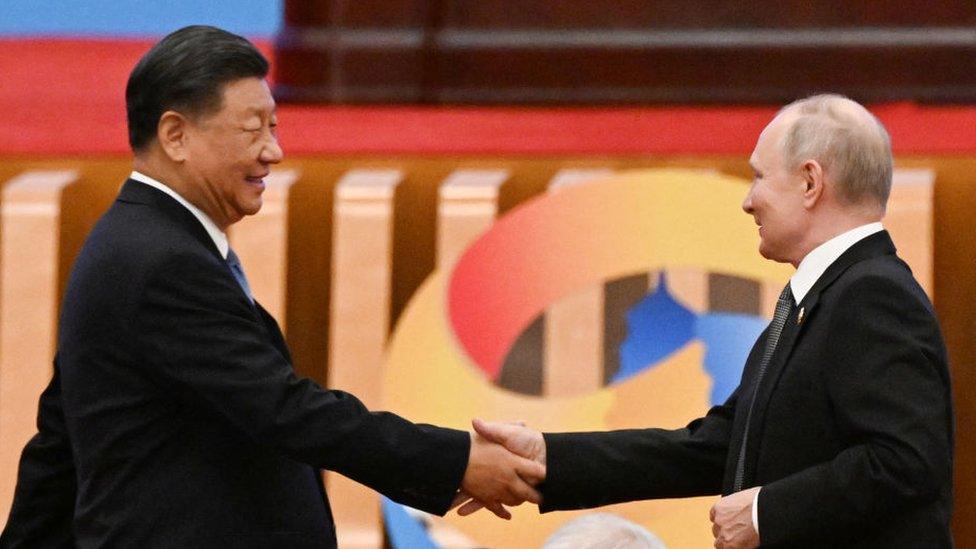

Russia's leader and China's foreign minister in talks

Vladimir Putin loves a really long table. Images of his meetings are famous, with the Russian leader at one end and the person he is speaking to so far away that you wonder if it is hard for them to hear one another.

It was not like that when he met China's top foreign policy official, Wang Yi.

There they were, sitting within handshake distance, with an oval-shaped table in the middle.

It could be that the proximity was achieved by seating placement at a previously used table, with the Chinese delegation directly across the middle rather than at the long ends but the effect was the same.

When the footage was released, it appeared to be a deliberately symbolic move to show that he felt safe enough to be that close to the representative of such an important friend.

Of course, it has not always been that way. Decades ago, Beijing's network of underground fallout shelters was designed to protect the citizens of the Chinese capital from a nuclear war with the Soviet Union.

Yet now Xi Jinping's administration sees Russia as a front-line enemy of US influence. A nation which - like North Korea - may be considered an international pariah but which serves a useful geopolitical purpose.

The Chinese government did not even seem that embarrassed when President Putin returned home from attending Beijing Winter Olympics, having proclaimed a new "no limits" relationship with China and, within weeks, launched the invasion of Ukraine.

Many have asked whether Mr Xi was warned about the imminent war when he sat next to his Russian counterpart who must have been considering barely anything else at the time.

China is walking along a very delicate path in its dealings with Russia over Ukraine. Mr Xi may feel like he is confidently striding down the track, but some think that the path is crumbling at the edges, with Beijing's claim to neutrality increasingly difficult to stand up.

Wang Yi comes out of meetings proclaiming that China and Russia are together promoting "peace and stability".

In other parts of the world, it will seem ludicrous to use expressions like "peace and stability" on a trip to Russia just before the first anniversary of that country's invasion of Ukraine.

Beijing knows this and yet decided to press ahead nevertheless, in the full knowledge that it will take a hit reputationally because it has calculated that it is more important to offer significant moral support to Vladimir Putin at this time.

When Wang Yi met Sergei Lavrov he said, "I am ready to exchange views with you my dear friend, on issues of mutual interest and I look forward to reaching new agreements."

Russia's foreign minister said the two were showing solidarity and defending each other's interests despite "high turbulence on the world stage", as if this turbulence was something floating in the ether rather than chaos of his own government's making.

Watch: Putin and Biden's speeches compared in under a minute

Earlier this week in Beijing, China's Foreign Minister Qin Gang warned that the conflict in Ukraine could spiral out of control if certain countries kept pouring fuel on the fire.

He was referring to the US, a country which is openly giving military assistance to the Ukrainian army but which has warned China not to provide Russia with weapons and ammunition.

Analysts are now asking what options China might consider if it looks like President Putin is facing a humiliating battlefield defeat.

Researchers in America say that Beijing is already supplying Russia with dual-use equipment, technology which can appear to be civilian but which can also, for example, be used to repair fighter jets.

It has also not tried to hide the fact that it is buying up Russian oil and gas to make up for markets its neighbour lost because of sanctions which followed the invasion.

And Vladimir Putin confirmed in his meeting with Wang Yi that his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping would soon travel to Moscow. It is thought this might happen in the coming months.

In a way, the Kremlin is doing China's dirty work. It is draining Western military resources and putting pressure on Nato and if Russia's economy tanks because of it, does that really matter to Beijing? It will just need more Chinese products for the recovery afterwards.

The problem is that Western countries have been quite united, Russia does not appear able to win and, increasingly, China is being seen standing side by side with a bully who forced a bloody, prolonged war on Europe.

China has to be careful not to bite off more than it can handle, but the rest of the world also will not want Asia's giant dragged into this war to a greater extent than it already is.

Related topics

- Published17 May 2024