India #flashreads seeks to defend free speech

- Published

Salman Rushdie was forced to stay away from the Jaipur literary festival

A group of Indians is pushing back at limits on free speech by encouraging public readings of banned or threatened works on 14 February. Literary critic and writer Nilanjana S Roy is one of those harnessing the internet to promote the events they're calling #flashreads.

As a group of friends helped put together a timeline of censorship, bans and assaults on artists and writers in India, all of us had the same reaction when we saw the final chart.

The 1990s and the 2000s saw ominous spikes on the chart - no gentle rising tide of intolerance here, but a steep climb, each dot on the curve representing an assault on an art gallery, a library, a cinema, a book ban, a book burning, the exile of an artist. Dark dots that represented threats, mobs and often, avalanches of legal cases.

This was just the map of challenges to artistic freedoms.

Teacup tempests

Our small group of lawyers, writers and middle-class professionals hadn't yet tracked the , external, or the worrying ways in which the state had begun to bar academics from coming into the country because of their reportage on Kashmir's mass graves, for instance.

There have been attacks on free expression in India

All of us were tired of reacting after the fact - condemning yet another political party capitalising on the law that allowed (and sadly, encouraged) groups to claim that their religious sentiments had been offended by a book, a work of art, a film, or as happened at the Jaipur Literature Festival (JLF), by the very image of Salman Rushdie's face on the screen.

#flashreads emerged out of the teacup tempests that erupted in January at the JLF.

Salman Rushdie was supposed to be one of the 260-odd invited writers, but fringe groups created a security threat to the author of The Satanic Verses.

On the first day of the festival, the organisers announced that Rushdie would not be able to come.

Later on the same day, four authors - Amitava Kumar, Hari Kunzru, Jeet Thayil and Ruchir Joshi - read at two separate sessions from Rushdie's The Satanic Verses in protest.

As protests went, it was a civil and timely gesture, and it belonged to an old tradition of protesting the 23-year-old import ban on the Satanic Verses, a backdoor ban aimed at preventing the sale of Rushdie's controversial book in India.

In the late 1980s, various groups of citizens had staged Satanic Verses readings - Swami Agnivesh and the lawyer Rajiv Dhawan among them.

Discontent

Twenty three years later, the response to the readings was revealing. The organisers distanced themselves from the four authors, and the ensuing debate focused more strongly on Rushdie's actions and the authors' motives in reading than it did on the elephant in the room.

We have grown so used to the threat of violence being employed to shut down everything from an essay on the Indian epic Ramayana in a university syllabus to novels that criticised politicians that our collective ire has become directed at those who might provoke violence, not at those who supported or started the violence. Protest is provocation, apparently.

February 14th is an interesting day in terms of free expression.

Several years ago, Hindu right-wing activists saw an opportunity as Valentine's Day caught on in India, and began sending mobs out onto the street in protest against "Western culture", external.

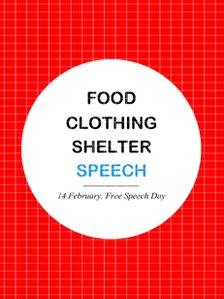

Sanjay Sipahimalani has designed a series of posters for #flashreads

These mobs were often violent, hostile to couples and their protests were clearly orchestrated with an eye to media attention.

The 14th was also the anniversary of Iran's Ayatollah Khomeini's fatwa sentencing Rushdie (and his editors and publishers) to death for publishing The Satanic Verses. It was the perfect day for a #flashreads for free speech.

#flashreads are a small way of channelling the simmering discontent felt by the silent minority.

Artists and writers don't make a vote bank. There is an invisible hierarchy of emotions at work in this new India, where the depth of someone's stated religious feelings can and do trump the depth of someone's stated belief in the free flow of ideas.

And when this silent minority has pushed back, it has almost always been defensive - after a ban or an assault on freedoms of one kind or another.

What we hope to do is to encourage people to find and shape their own way of protest. #flashreads is a crowdsourced idea.

Journalist Nisha Susan mentioned a possible Twitter protest, where you might tweet one line from a banned book; Heather Timmons of the New York Times heard me out when I spoke of encouraging people to do private readings and said, "Yeah, let's do flashreads." Critic Sanjay Sipahimalani designed free posters and others offered suggestions for Hindi #flashreads or spread the word on their blogs.

The idea is simple.

Find a few friends. Pick your favourite passages from challenged writings or your favourite passages about free expression. At a public place - a college canteen, a metro station, a marketplace - do a few readings.

If you like, talk about what free expression means to you in your personal and professional life. It's a small protest, and a collective protest - everyone is free to pick up the #flashreads idea and shape it the way they want.

Perhaps it will help us think about what free expression means to us; perhaps it will do no more than bring back the pleasure of reading in the open air.

It's just one small part of the growing anti-censorship movement we're seeing across India, where so many of us are looking for the country where the mind is without fear, as it once used to be.

- Published19 October 2011

- Published24 January 2012

- Published20 January 2012

- Published25 January 2012