Is hope a fiction for India's poor?

- Published

- comments

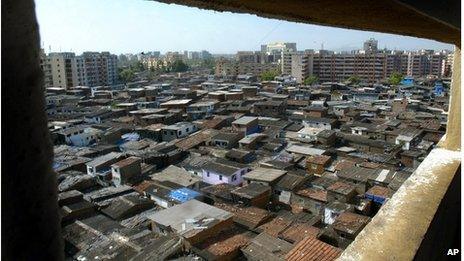

More than half of Mumbai's people live in slums

"We try so many things," a girl in Annawadi, a slum in Mumbai tells Katherine Boo, "but the world doesn't move in our favour".

Annawadi is a "sumpy plug of slum" in the biggest city - "a place of festering grievance and ambient envy" - of a country which holds a third of the world's poor. It is where the Pulitzer prize winning New Yorker journalist , externalBoo's first book Behind the Beautiful Forevers , externalis located.

Annawadi is where more than 3,000 people have squatted on land belonging to the local airport and live "packed into, or on top of" 335 huts. It is a place "magnificently positioned for a trafficker in rich's people's garbage", where the New India collides with the Old.

Nobody in Annawadi is considered poor by India's official benchmarks. The residents are among the 100 million Indians freed from poverty since 1991, when India embarked on liberalising its economy.

'Garbage justice'

Boo's story - a stirring and gritty non-fiction narrative, one of the best ever written by a foreigner on India - revolves around the self-immolation of a cantankerous, one-legged slum woman called Fatima Sheikh and how her neighbour and a hardworking, young garbage trader called Abdul and his family are framed on a charge of murdering her. Fatima's death is a liberation from enervating poverty, and a chance for some neighbours to make money from Abdul's family, who are making a bit more money than the rest from selling recyclables.

This is when Abdul realises that the Indian criminal justice system was a "market like garbage" - "innocence and guilt could be bought and sold like a kilo of polyurethane bags".

Boo adopted what she calls the "vagrant-sociology approach" and followed Abdul and his neighbours of this unexceptional slum over the course of several years - November 2007 to March 2011 - to see "who got ahead and who didn't, and why, as India prospered".

Katherine Boo's narrative is gripping and well-researched

She used more than 3,000 public records, many obtained using India's right to information law, to validate her narrative, written in assured reported speech. The account of the hours leading to the self-immolation of Fatima Sheikh derives from repeated interviews of 168 people as well as police, hospital, morgue and court records. Mindful of the risk of over interpretation, the books wears its enormous research lightly.

Boo's narrative is peopled by a vast range of gripping characters from Annawadi, the world from which New India shies away. An aspiring slum boss woman who volunteers for a local Hindu right wing party. A man who paints his horses with stripes and rents out the fake zebras to birthday parties of middle-class children. A corrupt nun who runs a children's home. A deranged man who talks to a luxury hotel building skirting the slum.

Then there's a bunch of young scavengers and thieves, ravaged by rats and high on white correction fluid, who live, work and die quickly. They are the young flotsam that India breathlessly parades as its demographic dividend when, in reality, the children, tired and brutalised, are already past their sell-by-date.

Bleak

The people of Annawadi are also caught up in the hideous web of corruption and official venality which hurts the poor most, and lead utterly dehumanising lives in a city that aspires to become India's Shanghai. It is far removed from the dreadful stereotype of the happy-poor Mumbai of Slumdog Millionaire, external.

The local councillor runs fake schools, doctors at free government hospitals and policemen extort the poor with faint promise of life and justice, and self-help groups operate as loan sharks for the poorest. The young in Annawadi drop dead like flies - run over by traffic, knifed by rival gangs, laid low by disease; while the elders - not much older - die anyway. Girls prefer a certain brand of rat poison to end their lives.

Behind The Beautiful Forevers is a bleak, heart-breaking book, which leaves you numb with anger, helplessness and pain. In this age of globalisation, Boo writes, hope is not a fiction. But hope flickers dimly in Annawadi as the "unpredictability of daily life has a way of grinding down individual promise".

Boo asks some uncomfortable questions: What is the "infrastructure of opportunity" in India? What capabilities does the market offer? What capabilities are wasted? Why don't places like Mumbai where filthy slums stand cheek-by-jowl with the world's priciest buildings explode into violence? Why don't unequal societies implode? What happens to the powerless when, among powerful Indians, the distribution of opportunity is "typically an insider trade".

Boo has an interesting take on corruption, rife in societies like India's. Corruption is seen as blocking India's global ambitions. But, she writes, for the "poor of a country where corruption thieved a great deal of opportunity, corruption was one of the genuine opportunities that remained".

On the other hand, Boo believes, corruption stymies our moral universe more than economic possibility. Suffering, she writes, "can sabotage innate capacities for moral action". In a capricious world of corrupt governments and ruthless markets the idea of a mutually supportive community is a myth: it is "blisteringly hard", she writes, to be good in such conditions. "If the house is crooked and crumbling", Boo writes, "and the land on which it sits uneven, is it possible to make anything lie straight?