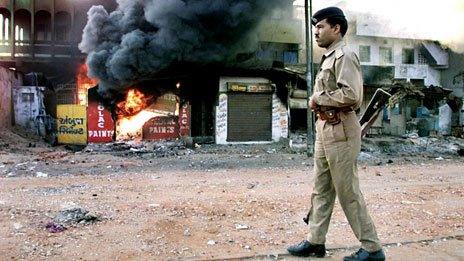

Has Gujarat moved on since 2002's riots?

- Published

- comments

A survivor cries inside her house that was burnt during the riots 10 years ago

"It was a blot on the state. It was deplorable," says Jay Narayan Vyas, a senior minister in the government of Gujarat, which exactly 10 years ago saw some of the worst religious rioting, external in India since Independence.

"But Gujarat has moved on. Nobody is concerned [about the riots any more] except the media and NGOs. Today, it's a bad dream."

We are sitting in Mr Vyas's home on a balmy Ahmedabad afternoon. A fan heater warms the room. His BlackBerry is charging, and a cassette of sacred Hindu chants lies by the side of a Bose sound system. A supplicant comes into the room and leaves behind some papers.

Mr Vyas is a 65-year-old bureaucrat-turned-politician whose website describes him variously as an "innovative moderniser" and "an expert enlighten globe with excellent solutions (sic)". The engineering graduate from the elite Indian Institute of Technology is also a "scholar, analyst, academician, administrator, manager and public life functionary".

Mr Vyas, more crucially, is a spokesman for the Narendra Modi-led BJP government in the state.

'Over-emphasised'

It is not an easy job.

Night after night, on news television, he gamely defends Mr Modi and his government against unrelenting allegations of not having done enough to stop the anti-Muslim riots that followed the burning of a train carrying Hindu pilgrims. More than 1,000 people, mainly Muslims, died because the government, many believe, failed to protect them.

Ten year after the riots, facing the inevitable question that continues to haunt his government, Mr Vyas puts up a swift defence.

Gujarat is one of India's most industrialised states

"We have come out of 2002. The event is over-emphasised, it's blown beyond proportions. Let us leave it behind and look ahead," he says.

So we leave the riots behind and move ahead.

Under Mr Modi's stewardship, Mr Vyas tells me, Gujarat has been recording scorching double-digit growth, prompting even The Economist magazine to call it India's Guangdong, external. Its manufacturing-driven, job-intensive economy, many believe, is touted as a model for the Indian economy.

I am walking briskly into the present and future now with Mr Vyas.

Gujarat, he says, produces 35% of India's pharmaceuticals, 60% of its salt, 90% of its soda ash, a sixth of its cement, and a third of its cotton. It has Asia's largest milk-processing unit. Its 21 ports handle a quarter of the cargo in India. It even produces 10% of the world's denim.

In an energy-starved country, Gujarat boasts round-the-clock power, thanks to some smart reforms by Mr Modi's government. Farm output is growing at nearly seven times the Indian average.

Not surprisingly, Mr Vyas proudly tells me, Gujarat's growth has been in the double digits for a decade now. It is one of India's leading industrialised states.

"Economic growth in Gujarat," he says, "is because of the state's ethos, culture, enterprise, give and take, large heartedness and the fact that it is accepting of everybody."

This is possibly the irony of Gujarat.

Openness and a breezy mercantile spirit come naturally to the people of a state which has nearly a quarter of India's coastline.

But it's also a state which has seen seven major religious riots between Hindus and Muslims since 1969, when 630 people died in five days of fighting in Ahmedabad. Gujarat also has the highest per capita rate of deaths in communal incidents, at around 117 per million of urban population. Religious violence here coexists with a high literacy rate.

Ghettoised

The 2002 riots were obviously the worst. More than 1,000 people, according to the government's own estimate, were killed. Property worth nearly $60m (£38m) was destroyed. An estimated 200,000 people were displaced. Ten years later, around 25,000 of them still languish in relief camps - this, in a state which won international plaudits for rehabilitating victims of a massive earthquake in 2000. Many have moved into newer ghettos. Ahmedabad is the most ghettoised city in India.

So is it easy for Gujarat's minorities to forget 2002 and move on, I ask Noorjehan Abdul Hamid Dewan, a 38-year-old woman, who lives in Johapura, Ahmedabad's biggest Muslim ghetto?

During the riots, Noorjehan risked her auto-rickshaw driver husband's ire to come out of purdah to help survivors in a relief camp in her neighbourhood. Since then she has been working tirelessly with them.

"How can people forget the riots and move ahead?" she asks. "People don't forget. They simply remain quiet in fear. We haven't forgotten a thing. We want justice and we will keep fighting for it."

This is a difficult task in what political scientist Christopher Jaffrelot calls the "dysfunctional" justice system, external in Gujarat.

If you are poor, fighting for justice can wear you out, rob you of your daily wage, and force you to cave in and compromise with the perpetrators of the violence in exchange for a little money. This is one of the ways you "move on".

Ahmedabad's Muslim community wants to move on, seeing justice done is part of that for many

Social activist Harsh Mander calls such compromises a "mode of survival for victims, in their highly unequal battle to rebuild their lives after mass violence".

The other way to move on is to have faith in a broken judiciary, and keep hoping that some justice, however incomplete, will happen.

Activists point out how more than 2,000 cases of violence were closed within months of the riots because of partisan investigating agencies and prosecutors and brazen intimidation of witnesses, even earning the opprobrium of the Supreme Court.

It was only in 2006, after the Supreme Court stepped in and ordered the reopening and a re-investigation of nearly 1,600 of these cases, that some hope was rekindled. Complaints were lodged, more than 40 police officers involved in the riots indicted and more than 600 people arrested for violence.

Two years later, the Supreme Court appointed a special team to investigate half a dozen key cases of violence. It also asked a trial court to decide whether Mr Modi should be probed in one of the cases. Even this intervention has had its share of problems - half of the investigators were selected from the already discredited local police force, for example.

Moving on

A few trials have been completed - in two major cases over the burning of the train in Godhra and an episode of violence in Sardarpura - among the 151 towns and 993 villages which were convulsed by riots - 11 people have been sentenced to death and 51 others sentenced to life in prison. "Justice," says activist Gagan Sethi, has been "exceedingly slow."

The 2002 riots were some of the worst India has ever experienced

Justice may be elusive, but Muslims, who comprise fewer than 10% of Gujarat's population, have moved on in their own small, meaningful ways in a state which many say does not do much to support them.

More and more Muslims are sending their children to schools and colleges. In 2002, there were 200 Muslim educational trusts in Gujarat. Now, there are more than 800.

"The reaction of the Muslim community has been very positive," says social scientist Achyut Yagnik. "Muslim women are also talking about more education. It's all about moving forward with education."

He is right. Everywhere I went, Muslim men and women spoke about the importance of education.

In Godhra, I met telecommunications engineer Mohammed Yusuf, 51, who spent a year in prison after being falsely implicated in bomb attacks. He is a soft-spoken man with a flowing beard.

"For long, we have lived as frogs in the well. Now we need to get out, educate and inform ourselves, know what our rights are, find our place in the world and defend our rights," he says.

Ten years. More than 1,000 lives lost. Broken lives. Scant justice.

But in Gujarat's frayed social fabric, hope still beckons.

- Published27 February 2012

- Published13 March 2012