India's thriving 'hereditary democracy'

- Published

Akhilesh Yadav (right) has taken on the mantle of his father (left), a former chief minister of Uttar Pradesh

India's "hereditary democracy" is thriving as never before.

A new generation of heirs has ascended democratically to power in Uttar Pradesh (Akhilesh Yadav, son of Socialist leader Mulayam Singh Yadav), Punjab (Sukhbir Badal, son of Chief Minister Prakash Singh Badal) and Uttarakhand (Vijay Bahuguna, son of legendary Congress leader Hemvati Nandan Bahuguna).

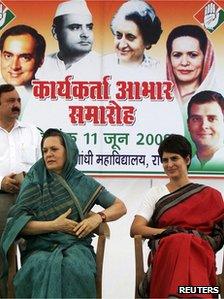

Other political heirs such as Rahul Gandhi (son of Rajiv Gandhi, grandson of Indira Gandhi and great-grandson of Jawaharlal Nehru) and many others who tried their luck at the hustings unsuccessfully, are back in the trenches preparing for the next battle.

They are being increasingly accepted as normal political actors. In fact, the media fawn over them, seeing nothing unusual in their victories and defeats.

"Hereditary democracy" is different from political dynasticism as the latter can exist under non-democratic systems as well - in North Korea, for example, or in monarchic or feudal states in earlier times.

It uses the dynasty as the launching pad for contesting elections and becomes legitimate after winning democratically contested elections.

Patronage networks

Hereditary democrats have the advantage of having both the tangible and intangible resources needed to participate in democratic politics.

The Nehru-Gandhi family's model of hereditary politics was replicated in the states

They have the economic resources as well as the patronage networks or the social capital accumulated over time because of the position of their family, caste and clan in the community.

This gives them relatively easy access to prestige, politics and power.

It also imbues them with what is residually described as charisma - a quality which allows them to bypass political party structures and address the masses directly with a confidence which takes the appreciative audiences by surprise.

The normal rules of party discipline and institutional norms do not apply to them.

But why was Rahul Gandhi not as successful as Akhilesh Yadav?

In India, it seems that there are two models of hereditary democracy.

One model is of families which contest elections generation after generation and take on political responsibilities.

Those dynastic heirs who themselves contest elections have included the first political family of India - the Nehru-Gandhis up to the time of Rajiv Gandhi, the Badals in Punjab, the Mulayam Singh Yadav family in Uttar Pradesh, the Karunanidhi family in Tamil Nadu and the Abdullahs in Jammu and Kashmir, among others.

The Nehru-Gandhi family's model of hereditary politics was replicated in the various states of India through party officials and legislators.

The Congress party was partly based on the local patronage networks that these locally influential political families brought with them.

The other model is of families which control political parties, their finances, dictate their political agenda but keep themselves away from the hurly-burly of elections.

In this category come the Thackerays of Shiv Sena and the Maharashtra Navnirman Sena (MNS).

Neither Shiv Sena supremo Balasaheb Thackeray contests elections nor do his son, Uddhav Thakre and nephew Raj Thakre, who controls the MNS, a breakaway group of Shiv Sena.

Remote control politics

The Nehru-Gandhi family model of contesting elections to take on direct political responsibility, however, was given up by Sonia Gandhi in the post-Rajeev Gandhi era.

She was instrumental in securing the peoples' mandate for the Congress as the single-largest party in the 2004 and 2009 general elections.

She contested as did her son Rahul Gandhi, both winning their constituencies.

Badal father (right) and son (left) are now in charge of Punjab state

However, instead of taking on the political responsibility herself of forming a government, she chose to relegate it to Manmohan Singh, a member of the upper house whose experience of a direct election was limited to 1999 when he lost in the middle-class constituency of South Delhi.

This shift closer to the Thackeray model of politics-by-remote-control has worked well for Sonia Gandhi in Delhi but did not work for Rahul Gandhi in Uttar Pradesh.

The Thackeray model works essentially because it is local and based on violence and intimidation.

They appeal to the worst kind of local insecurity, of Marathi speakers being swamped by outsiders. They remain avowedly local. If they resided in Delhi but contested elections on the same anti-outsider issue in Maharashtra, they would lose.

So this strategy did not work for Rahul Gandhi at all in Uttar Pradesh.

At no point was he a chief ministerial candidate and nor did he demonstrate any personal commitment to the people of the state.

Indeed, Congress General Secretary Digvijay Singh admitted as much after the dismal electoral defeat of the Congress party, saying that Rahul Gandhi was not an issue in the elections.

Cycle perpetuated

By contrast, Akhilesh Yadav was in Uttar Pradesh for keeps - his family and village are there, his early schooling was there, he partly lives there, and he was raring to take over his father's mantle in the state.

Uttar Pradesh voted for a political family, but one which was willing to take political responsibility and was not going to delegate it to someone else.

What then is the future of hereditary democracy in a society in transition from feudalism to capitalism?

Even as the older patronage networks are being replaced by newer ones, one finds that the political heirs face no major threat at all from greater democratisation of society.

Identity-based political parties in India do not seek rights and privileges for individual citizens but for their caste, clan or ethnicity.

These demands are often articulated by the vocal sections among these groups - essentially those already privileged within that group. As these dominant families are accommodated in representative politics, they tend to perpetuate the same old cycle.

Bharat Bhushan is a Delhi-based journalist

- Published7 March 2012

- Published6 March 2012

- Published6 March 2012

- Published24 May 2019