India climbdown may help China border dispute

- Published

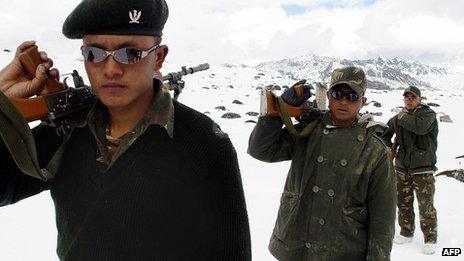

China and India fought a brief war over their disputed Himalayan borders in 1962

Fifty years after India and China fought a month-long war over their disputed Himalayan territory, hopes of a solution to the boundary dispute seem to be emerging.

India seems to be climbing down from a stiff position that not an inch of its land can be given away to China to resolve the border dispute that has dogged the two Asian giants since the 1950s.

"It is important to solve the India-China border dispute and for that some give and take is necessary," said retired General JJ Singh.

"India will have to move away from our position that our territory is non-negotiable," he said.

Gen Singh did not specify the "give-and-take" he thought necessary, but specialists feel that he was hinting at India accepting some of the Chinese positions on the disputed Himalayan border and vice-versa.

Gen Singh is now governor of the frontier state of Arunachal Pradesh, the whole of which is claimed by China as its own.

Chinese maps mark the state as Southern Tibet and when the Chinese claim line was posted on Google earlier this year, it led to a furore in India.

Both countries have frequently accused the other of border incursions, but Gen Singh said they occurred because both armies go by their own conflicting versions of the border.

Giving the inaugural speech at a national seminar on Indo-China relations organised by the Indian Council of Social Science Research and Rajiv Gandhi University, Gen Singh made a strong plea for normalisation of Sino-Indian relations.

"The world has changed and we are a much more confident nation now. It is important to realise that we need a speedy resolution to the Indo-China boundary dispute and for that some give-and-take may be necessary."

However, he did not spell out where India might need to concede to Chinese positions and vice-versa.

"By and large, the McMahon Line will help resolve the boundary of the two countries but some incongruities apparent on the ground might have to be amicably resolved and there is no scope for conflict as we have agreed to resolve the issue peacefully," the Arunachal Pradesh governor said.

The McMahon Line was drawn up by British India's Foreign Secretary, Sir Henry McMahon, in 1914 but is not accepted by China.

'Competitors, not rivals'

The way Gen Singh lashed out at those who predict a future Sino-Indian war indicates that the Indian establishment is keen to build bridges with China by controlling the tensions that have cropped up in recent months.

"A governor of a state bordering China would not make such an important statement unless he had been cleared to do so by Delhi," said CJ Thomas of the Indian Council of Social Science Research's North-eastern chapter.

Predictions of a looming Sino-Indian war were "utter nonsense", Gen Singh said.

"I must tell these futurologists and experts to stop this nonsense of predicting a Indo-China war, first in 2010, then in 2012 and now in 2020. They will be proved wrong as we will not fight. We are competitors, not rivals," he said.

"These experts have no ground knowledge, they don't know that Chinese and Indian soldiers actually play volleyball on the borders.

"We have plans for extensive military-to-military interactions between the two countries," Gen Singh told the conference. "That includes joint military exercises."

He said India will nevertheless not compromise on its military preparedness.

But the governor said there was no scope for a purely militaristic approach and it was equally important to develop Arunachal Pradesh by utilising its considerable resources so that the "very patriotic Arunachalis" feel more and more strongly about defending their land against any possible aggression.

Talking of Chinese territorial claims on the area, Gen Singh said: "Our Chinese friends should come here and find out for themselves what the Arunachalis feel about China and India. Nobody here wants to be part of China."

Swap offer

Many China specialists in India have welcomed Singh's statements.

"We need a pragmatic approach to resolve the border dispute, said CV Rangnathan, a former Indian ambassador to China who also attended the conference.

"We can't keep the matter hanging and a give-and-take approach is the best way to do it."

Hands across the border: Scope to peacefully resolve the border dispute, says Gen Singh

"It is high time the sabre-rattling and one-upmanship stopped and China and India find a way to resolve the festering border dispute," said China specialist Shrikant Kondapalli. "That will take both countries forward."

China claims about 90,000 sq km (35,100 sq miles) of what India says is her territory, mostly in the eastern part of their shared border.

India has been reluctant to part with any portion of the disputed territory since the 1950s. It rejected a swap offer made by China's former Prime Minister Zhou Enlai in 1960, asking India to recognise China's control of Aksai Chin in the west as a quid pro quo for China's recognition of the McMahon line.

After rejecting that offer, India initiated a "forward policy" to control the disputed territories in the Himalayas.

Many specialists like Neville Maxwell, author of India's China War blame this policy for the 1962 war between the two countries, in which the India army was routed and the Chinese almost reached the plains of Assam before withdrawing to their present positions on the Tibet-Arunachal border.

- Published13 December 2011

- Published11 April 2011