India's frustration with Sri Lanka over Tamils

- Published

President Rajapaksa has yet to act on promises of greater rights for Tamils

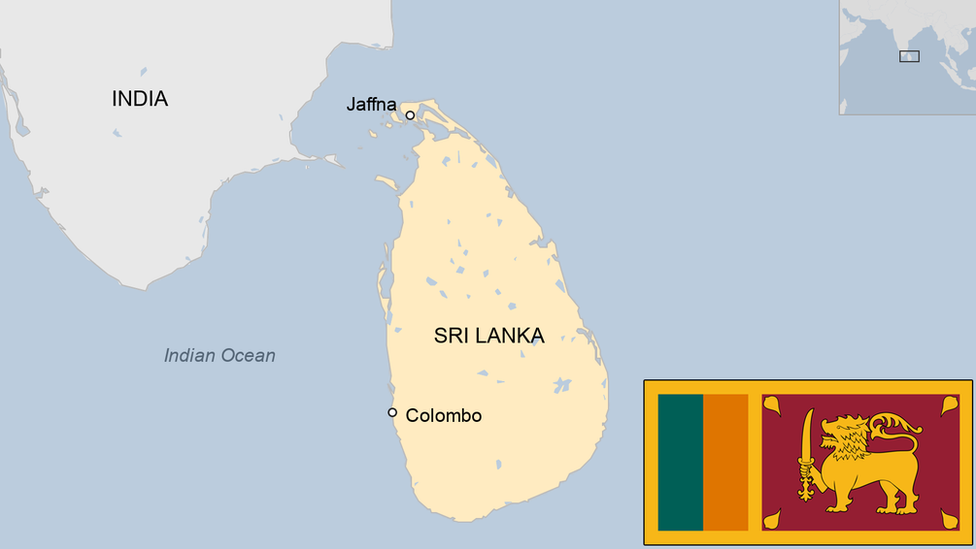

Indian disappointment with Sri Lanka's refusal to undertake genuine reconciliation with its Tamil population ought to have been apparent to Colombo for some time now.

It must have been brought home forcefully with the visit of an all-party delegation of Indian parliamentarians to Sri Lanka last week.

Although India supported the war against the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam it was wrong to presume that it would turn a blind eye to Colombo's indifference towards resolving the Tamil question since the war ended three years ago.

Its error should have been apparent to Colombo when Delhi voted for the resolution in the UN Human Rights Council castigating Sri Lanka for the abuses committed by its armed forces against the Tamil militants during the three decades of war.

The parliamentarian delegation, the first high level one from India after the UN vote, was led by opposition leader Sushma Swaraj.

While MPs from the Tamil parties DMK (Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam) and the AIADMK (All India Anna DMK) had withdrawn from it, the other members - including some Tamil speaking MPs - were also of two minds because of aggressive statements on the Koodankulam nuclear power plant in Tamil Nadu state by a Sri Lankan minister virtually on the eve of the visit.

Despite the situation not being politically propitious, the delegation still went ahead.

Sushma Swaraj made only one public statement at the end of the visit.

She urged Colombo to "reach a genuine reconciliation" based on "a meaningful devolution of powers which takes into account the legitimate needs of the Tamil people for equality, dignity, justice and self-respect".

The opposition leader spoke in the same voice as the government of India - suggesting that there was weariness across the political class in India with Colombo's reluctance to devolve power to Sri Lanka's Tamil minority.

Emotional echo

The shift in India's position towards Sri Lanka as manifested in the UN Human Rights Council vote has been ascribed to several factors.

One theory is that there was a backroom deal between the national government and Tamil Nadu Chief Minister J Jayalalithaa that she would allow the Koodankulam nuclear power plant in her state to become operational if the government voted for the resolution.

Other theories are that the government was forced to keep the DMK in good humour due to coalition compulsions and that India gave in to US pressure to support the Washington-sponsored resolution on human rights violations in Sri Lanka.

It would be an error to conclude, however, that such tactical factors alone were responsible for the change in India's position.

Indian opposition leader Sushma Swaraj - taking the government line on Sri Lanka

What happens to Sri Lankan Tamils has an emotional and often a political echo in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu.

Even during the conflict with the LTTE, while India supported military action against the militant forces, it always cautioned Colombo about protecting the rights of the Tamil civilian population and ensuring their welfare.

President Mahinda Rajapaksa has assured India several times about his commitment to a constitutional amendment to devolve powers to the Tamils.

It was passed in 1987 as a result of the Indo-Sri Lanka Accord but its legality has been questioned in the Supreme Court.

So although President Rajapaksa talks of a devolution process that would be more than that promised earlier - he calls it "13th amendment PLUS", there is uncertainty about what this would mean.

Many ministers in the Rajapaksa government are openly opposed to devolution and the president himself seems to be backtracking on it. A parliamentary select committee which will make suggestions on the Tamil issue is yet to be set up.

Indian unity

Colombo, however, has failed to read India's disappointment with bilateral efforts. If it had started negotiations for devolution with the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), the UNHRC resolution imbroglio may not have taken place.

The all-party parliamentarians' delegation emphasised these issues - urging that a dialogue be restarted in which the TNA is given an honourable role and that the parliamentary select committee on devolution be set up soon. Most importantly, it left Colombo in no doubt that the Indian political parties were united on this issue.

Having created an anti-West frenzy it may not be easy for the Rajapaksa government to back away from it.

It derives its social power from a peculiar psyche - of Sri Lanka (that is, the majority Sinhalas) being isolated by evil powers.

However, the Rajapaksa government could still move in the direction that Delhi is pushing it.

While maintaining its anti-West, anti-imperialist facade, it could compromise on implementing the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission's recommendations. That would be the pragmatic way forward. Delhi after all is not seeking regime change in Colombo.

The visit by Indian parliamentarians shows that the Indian policy of engagement with Colombo will continue unabated. However, so will the pressure for a permanent reconciliation with the Sri Lankan Tamils.

- Published4 October 2024

- Published9 January 2015