Rebuilding lives in Kashmir

- Published

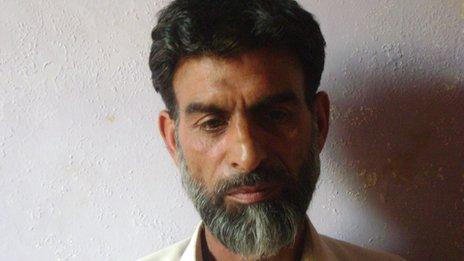

Ejaz Ahmad and his family spent almost all their savings on the return journey

More than 20 years after they took up arms to fight Indian rule in the Kashmir valley, many of the local insurgents are now returning home after renouncing militancy. The BBC's Geeta Pandey met some of them.

Abdul Rashid Khan was 14 when he ran away from home in Indian-administered Kashmir to join the jihad against India.

He remembers the year was 1989, but is not too sure about the month - "it could be September or maybe it was October".

"I was in school, in eighth standard. That day I had an exam to write. I finished the paper, dumped my school bag in a shop and left for Pakistan-administered Kashmir. It was 1:30pm and I was still wearing my school uniform, I took nothing with me," he says.

Mr Khan lived in Kulangam town in Kupwara district - not far from the Line of Control which divides the disputed region of Kashmir between India and Pakistan.

He left with a group of eight boys, "all students like me, some from Sopore, some from Srinagar".

"There was a sort of wave then, so I also went," he explains.

By next evening, the group had reached the Jammu and Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF) camp in Muzaffarabad in Pakistan-administered Kashmir.

"There I received a month of training in how to use a Kalashnikov assault rifle."

After more than 22 years, Abdul Rashid Khan is now back in Kulangam.

Trickle - not flood

He was among thousands of Kashmiri youths who, from 1988, crossed over to the Pakistani side to join militant training camps there and fight for freedom from India.

According to Kashmir government estimates, some 3,500 to 4,000 "boys" went to Pakistan over nearly two decades.

But in the last 12 months, at least 150 of them have come back, Indian officials say, and hundreds others are waiting to return.

The trickle which started last year is not yet a flood, but it's steadily gaining momentum.

Indian officials say they have received 1,054 applications from those wanting to return - by early August they had cleared 291 of them and say 300 more are to be cleared soon.

And many of the returnees, including Abdul Rashid Khan, have come back with their families.

Returnees say their reasons for doing so are many - diminishing support from the Pakistani establishment for the Kashmir cause, the growing Talibanisation of Pakistan, a realisation that the Kashmir jihad is "futile", homesickness and the Indian government's offer of amnesty to those willing to return.

In November 2010, the Indian government announced "a policy to allow for return of ex-militants to Jammu and Kashmir state", external.

Under the scheme, applicants could fill in a form and, if approved, return via the Wagah border in Punjab, through the Chakan-da-Bagh crossing on the Line of Control or fly into Delhi airport. The scheme was a god-send for Kashmiris looking for a way back home.

Ejaz Ahmad, 52, who went to Pakistan in August 1990, returned home from Muzaffarabad last month with his wife and five children.

"About a year and a half ago, I saw a Kashmir assembly debate on the TV news, where I heard them say that those wanting to come back would be allowed to return.

"The government said the returnees would be treated with respect, they would be rehabilitated here properly. Both the government and the opposition parties seemed to endorse that view so I decided to come back," he says.

But his return journey was far from smooth.

'Debrief-centre'

"To implement this policy which would allow the ex-militants to return, India needed Pakistan's co-operation, but Pakistan wouldn't agree because they have always said that these people had gone to Pakistan as they were victims of persecution in India," a senior Jammu and Kashmir government official told the BBC.

Abdul Rashid Khan returned home with his family after 22 years in Pakistan

But Kashmiris impatient to return home have found a way around this - they are returning via Nepal.

And that's the route Abdul Rashid Khan took in May, along with his schoolteacher wife Zeba and their three children.

"When I heard that the situation in Kashmir was improving, I told her, let's go home."

The Khans were part of a large group of 40 returnees.

"We travelled on Pakistani passports to Nepal. The first day we checked into a hotel in Kathmandu as Pakistani citizens. The next day, we destroyed our passports and drove up to the Indian border near Gorakhpur in Uttar Pradesh state," he says.

They were detained by the Indian army, but after cross-checking with police in Kashmir, the group was allowed to travel first to Jammu and then to Srinagar.

In Srinagar, they were taken to a "debrief centre" where they were interrogated for two days by the police, intelligence agencies and security forces before being handed over to their families in Kashmir.

Everyone in Indian-administered Kashmir I spoke to agreed that the former fighters could not return in such large numbers without tacit support from Pakistan.

"Pakistan must be aware of what's going on," a senior intelligence official in Srinagar said.

"I think it's just choosing to look the other way while these people leave. It's okay as long as they cross the border illegally, keep it low-profile, because some people, some agencies may not like it," he said.

Abdul Rashid Khan says: "Pakistan is definitely involved. If the two countries didn't have an agreement, there's no way I would be allowed to get away."

'Sacrificial goats'

The return of the ex-militants is a win-win situation for India.

First, as more and more of them come back, it means the number of potential armed fighters is shrinking and India has fewer of them to worry about.

Secondly, Delhi can tell the world the situation in Kashmir is normal - so normal that even the former fighters are coming back.

And thirdly, it also gives India an opportunity to discredit the separatist leaders - many of the returnees accuse senior separatists of prospering from the years of militancy while ordinary Kashmiris have been used as "sacrificial goats" in the fight for freedom which remains elusive.

Militancy in Indian-administered Kashmir is on the wane

But, the return of the former fighters is also posing a set of challenges for the Indian authorities.

"The ex-fighter is a local Kashmiri and he has parents or family here, he went to school and college here, he has documents to prove his identity," a senior bureaucrat says.

"But the problem is regarding their Pakistani spouses or children who are foreign citizens who have entered India illegally. Also, because they have destroyed their Pakistani passports, they have no documents to prove their identity.

"What do we do with them now? We have taken it up with the government, we have to find a way of legalising them," he says.

The returnees and their families, meanwhile, are beginning to grow impatient. When I visited Abdul Rashid Khan at his home in Kulangam recently, he was supervising a new home he's building for his wife and children.

Zeba, his wife, says moving to Kashmir has been "the biggest mistake of my life".

The move to a "remote village" on the India-Pakistan border has left her frustrated.

"I feel Kashmir is stuck in the 1950s," she says.

"India and Pakistan have moved ahead, but this region is very backward. We have long hours of daily power cuts, there's a water shortage and no gas. There are no roads here, no hospitals in the village. At 7pm, all the markets shut and transport stops."

It's not just Kashmir's lack of development that Zeba finds difficult to adjust to - what rankles most is the loss of her identity.

"We came to Kashmir because my husband said 'my parents and my family are all there, my land and property is there, our children's future is not in Pakistan, they have an identity only in Kashmir'.

"I came here searching for their identity, but now I've lost my own. I say I am from Pakistan, but I have no papers to prove it," she says.

Her children - seven-year-old twin daughters and an eight-year-old son - have been admitted into a local school, but those returning with older children say they are being asked for school-leaving certificates.

'Design flaw'

Many returnees are also finding it hard to find jobs and have little money as a result.

Ejaz Ahmad exhausted almost all his savings on his return journey - he had to pay close to 300,000 Pakistani rupees ($3,184; £2,039) to arrange travel documents and tickets for his family.

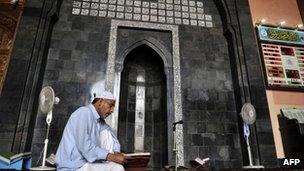

Naseer Ahmad returned after 11 years with his wife and two young sons

And because they had entered India illegally, they had to seek bail from a court which cost him 210,000 Indian rupees ($3,801; £2,430).

Now, he wants the government to keep its promise of rehabilitating the returnees which, for him, means travel documents for his family and school admission for his children.

Mr Ahmad says he is in touch with about 20 returnees and they are planning to take up the issue with the state administration.

The authorities admit that there is a "design flaw" in the amnesty scheme and that there is no agreement yet on how to deal with the returnees' spouses.

"The issue of the wives is a tricky one - she's a foreign national. And she's stateless at the moment, but we want to assure them that we are thinking about them," a government official said.

"We are also hoping to put systems in place to ensure they have livelihoods and that they are integrated into the system here."

But the returnees want action now.

"If I don't get documents soon. I'll try to run away. I don't know where I will go, but I've had enough," says Zeba Khan.

Abdul Rashid Khan says he gave up militancy because he does not believe in fighting any more.

But, he says, unless the government does something to address their problems soon, he may be forced to do something illegal.

"It may be a repeat of the 1990s," he warns.

Is India listening? Or will it let him down a second time?

- Published8 August 2012

- Published1 August 2012

- Published31 May 2012