India’s enduring problem with malnutrition

- Published

Andrew North reports

Deshraj reaches out for his mother's breast as she balances him on her knees, sitting outside her low, mud-walled home.

The little boy cries, but with no strength.

Deshraj is two years old but barely larger than a newborn and crazed by hunger.

His hair is patchy, his eyes are sunken and his legs like twigs - he is so weak he can't even walk.

But his mother turns him away; she has nothing left to give.

"We can't get him to eat bread," she says in an irritated tone, clearly annoyed at being asked questions, and walks away.

Deshraj is one of millions of Indian children suffering severe malnutrition, an enduring problem Prime Minister Manmohan Singh has called a "national shame".

Yet despite supposedly spending billions of rupees on poverty and food-relief programmes - and during a period of sustained economic growth - the government has made only a dent in the problem.

It is estimated that one in four of the world's malnourished children is in India, more even than in sub-Saharan Africa.

Weakened by hunger, they are more vulnerable to disease, with tens of thousands dying every year. Millions more will be physically and mentally stunted for life because they don't get enough to eat in their crucial early years.

'Hunger belt'

India has fallen in child development rankings, putting it behind poorer countries such as neighbouring Bangladesh or the Democratic Republic of Congo, according to a new study by the Save the Children charity.

So when UK Prime Minister David Cameron hosts a summit this weekend on child malnutrition worldwide, India is one of the countries of greatest concern.

Yet this is hardly a new problem. India has been arguing over what to do about hunger and the poverty that underpins it for years - while its farms produce ever more food.

The feeding centre in Markheda village is empty apart from a few sacks of emergency food

On paper there is already a multi-billion dollar network in place to look after children like Deshraj.

But too often, corruption and mismanagement mean it doesn't work.

Deep in the so-called "hunger belt" of central India, Deshraj's village, Markheda, has a government-subsidised food shop funded by the Public Distribution System (PDS).

It entitles every family living below the official poverty line to 35kg of grain or rice a month.

His extreme case is known too: he has been identified as one of 19 "dangerously malnourished" children in the village, making him eligible for emergency help from the local "nutrition rehabilitation centre" in the nearby town of Shivpuri.

But here it gets even more complicated.

"His family won't agree to send him," complains one of the health workers who suddenly arrive in the village while the BBC is there.

It is true that Deshraj's mother does not appear overly concerned about his condition. Like most people here, she's illiterate and doesn't seem to understand many of the questions she is asked before walking away.

"Sometimes the mothers don't know how best to look after their children," says the health worker.

There are other boys and girls in this settlement of about 600 families who appear in better, although far from perfect, health.

Bottom rung

But it's questionable too how committed the local authorities are to helping remote villages like this.

Markheda's residents are all tribals, on the bottom rung of India's complicated social ladder and largely out of sight. No one would find this place by accident, a half-hour drive through scrub and forest from the nearest road.

Villagers say the government PDS store is usually closed. It just happens to be open when the BBC visits, but inside it is empty apart from a few small sacks of emergency food left in one corner.

"I can't remember when we last saw someone from the government here," says one villager.

And Om Prakash, the government team leader, admits they came to the village because "we wanted to see what you were doing".

In another hut, Dineshi and her husband Brijmohan are still mourning their four-year-old son, Kalua, who died a few weeks ago.

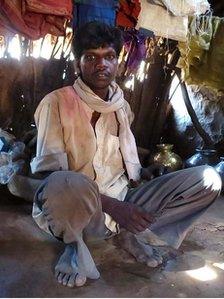

Brijmohan's four-year-old son died due to lack of medical care

"He got sick and stopped eating," says Brijmohan.

"We'd taken him to the doctor once before but we couldn't afford to go again and he got weaker and weaker."

There is no doctor nearby, and they have no transport. The family's only income is from selling baskets Brijmohan makes from tree saplings.

Blades of light pierce the gloom through holes in the thatched roof, catching their three-month-old son Mukesh as his mother Dineshi rocks him in a small hammock to relieve the thick summer heat.

He is still being breast-fed: the problems for children usually begin after six months, once they should start on solids.

The family gets food from the government PDS store, but sometimes "there's not enough, or it's bad quality".

"We're often hungry," Brijmohan says.

But there are plenty of people committed to tackling the problem.

At the nutrition rehabilitation centre in Shivpuri, Dr Raj Kumar is checking on a two-year-old girl called Anjini, brought in about a week earlier weighing just 3.8kg.

Many children are born heavier than that. Anjini has also picked up TB and pneumonia - common conditions among malnourished kids.

She is still in a dire state, barely able to lift her stick-thin limbs, but with constant feeding at the centre she has put on weight.

Dr Kumar says she will survive, but "she will be stunted for life".

'Left to rot'

Under pressure, India's ruling coalition introduced a Food Security bill last year, supposed to enshrine the right to food for all. But no one is betting on when it will be passed amid the country's current political deadlock.

And some critics say there is still not enough political will to tackle the hunger problem.

Other more free-market oriented voices argue that the whole approach of subsidising food and providing guarantees is wrong, simply creating a dependency culture.

India has had yet another record harvest

What is really needed, suggests Arti Tivari from the nutrition centre, is for existing programmes to be "implemented properly and for people to do their jobs properly" - a polite way of saying that graft and corruption still infect the system.

It is a simple fact that no Indian child needs to go hungry.

A short drive from the nutrition centre is a massive grain warehouse, sacks of wheat piled nearly to the ceiling - part of a network of government food stores across the country.

For years now, India has been producing more food than it needs. Yet every year large quantities simply rot in these warehouses.

The situation is much better than a decade ago, insists government minister Sachin Pilot, whose portfolio is officially telecoms but who has become closely involved in food policy.

But he admits "it's unacceptable having so many children with pot bellies and stick legs".

India still has a very young population, and politicians often talk of this future "demographic dividend".

But there will not be much of a dividend if so many Indian children continue to be held back and stunted in their first years of life.

- Published21 December 2011

- Published10 January 2012