Viewpoint: Is the Non-Aligned Movement relevant today?

- Published

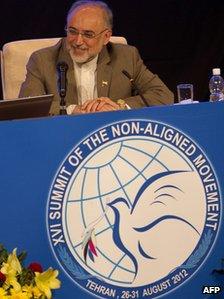

The 16th Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement is being held in Iran

As Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh arrives in Tehran to attend the 16th Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement (Nam) along with a hundred of his counterparts, questions are understandably being raised about the relevance and direction of the movement itself.

Born half a century ago in the middle of a world riven by antagonism between the USA and the USSR and the alliances they led, Nam had been the vehicle for developing countries to assert their independence from the competing claims of the two superpowers.

But with the end of the Cold War, there are no longer two rival blocs to be non-aligned between, and many have questioned the relevance of a movement whose very name signifies the negation of a choice that is no longer on the world's geopolitical table.

With the passing of the binary superpower-led world, Nam has redefined itself as a movement for countries that are not aligned with any major power.

'Western imperialism'

Since this is a state of affairs that is true of most countries in the world outside Nato, the globe's only surviving military alliance, it is hardly sufficient to justify the maintenance of the movement.

For India the non-aligned movement remains a necessary reflection of its anti-colonial heritage.

So Nam has been shaping a persona that is increasingly vocal about resisting the hegemony of the sole superpower, the US, and in asserting the independence of its members - overwhelmingly former colonies in the developing world - from the dominance of "Western imperialism".

The somewhat old-fashioned sound of the term revives charges that the movement is out of date.

More seriously, this perception is compounded by the increasing visibility within Nam of countries like Iran, the current Chair of the movement, and Venezuela, its designated successor - both nations whose strident hostility to the US underscores Nam's anti-Western image.

The very location of the summit serves to undercut the West's attempts to isolate Iran internationally and so proclaims Nam's defiance of the currents of the times.

Does such an orientation sit well with the rest of the membership, which includes such partners of Washington as India, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Kenya, Qatar and the Philippines?

Some of these countries would probably feel less comfortable with the political rhetoric of Nam than with its economic arguments at a time when predatory global capitalism is increasingly under challenge around the world - but others have been noticeably receptive to US economic policies.

In any case economics is the domain of the G-77, the "trade union" of the developing world, not Nam, whose raison d'etre is political.

Nam does, however, embody the desire of many developing countries to stake out their own positions distinct from the Western-led consensus on a host of global issues - energy, climate change, technology transfer, the protection of intellectual property specially in pharmaceuticals, and trade, to name a few.

In its determination to articulate a different standpoint on such issues, Nam embodies many developing countries' desire to uphold their own strategic autonomy in world affairs and the post-colonial desire to assert their independence from the West.

Necessary reflection

The ongoing "Arab Spring" that has convulsed the Middle East has affected several Nam members directly.

The countries that have undergone the most significant changes - Egypt, Libya, Tunisia and Syria - are all members of NAM.

Iran is the current Chair of the movement

The movement should therefore be a logical vehicle to pursue a resolution of the issues swirling around the turbulence of the region.

But its members are too hopelessly divided to forge a common position - and the anti-Assad views of many of them on Syria, for instance, are not very different from those of the West.

Nonetheless the Nam summit is expected to discuss the developments in the Arab world in the hope of evolving a shared understanding of the region's future evolution.

Whether this will amount to much more than words remains to be seen.

For a country like India, whose two decades of economic growth have made it an important player on the global stage, the non-aligned movement remains a necessary reflection of its anti-colonial heritage.

But it is no longer the only, or even the principal, forum for its international ambitions.

In the second decade of the 21st century, India is moving increasingly beyond non-alignment to what I have described, in my recent book, Pax Indica: India and the World of the 21st Century, as "multi-alignment" - maintaining a series of relationships, in different configurations, some overlapping, some not, with a variety of countries for different purposes.

Thus India is simultaneously a member of the Non-Aligned Movement and of the Community of Democracies, external, where it serves alongside the same imperial powers that NAM decries.

It has a key role in both the G-77 (the "trade union" of developing countries) and the G-20 (the "management" of the globe's macro-economic issues).

An acronym-laden illustration of what multi-alignment means lies in India's membership of Ibsa, external (the South-South cooperation mechanism that unites it with Brazil and South Africa), of RIC (the trilateral forum with Russia and China), of Brics (which brings all four of these partners together) and of Basic, external (the environmental-negotiation group which adds China to Ibsa but not Russia).

India belongs to all of these groupings; all serve its interests in different ways.

That is the manner in which India pursues its place in the world, and the non-aligned movement is largely incidental to it.

- Published29 August 2012

- Published29 August 2012