Why India may not be such an attractive destination for supermarkets

- Published

- comments

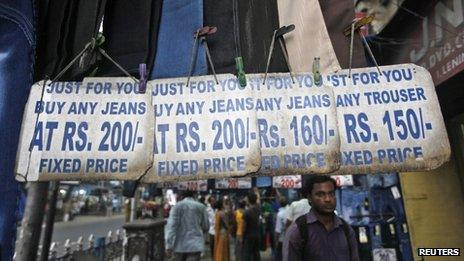

Mom-and-pop shops dominate the Indian retail landscape

Is India really an attractive destination for global supermarkets?

On Friday, the government finally cleared a controversial plan to open up its lucrative retail sector to global supermarket chains in an effort to revive a flagging economy.

There has been a massive political kerfuffle over how the supposed invasion of global chains will destroy India's fabled "mom-and-pop" stores, which have a stranglehold on the retail market.

Yet, it may be much ado about nothing, say many analysts. The political outrage against the government's decision - which actually comes with several business inhibiting caveats - is outsized, they insist.

Yes, India's growing economy, favourable demographics and an upwardly mobile middle class do portend a healthy future for organised retail.

Only, one doesn't quite know when the future will arrive.

At a paltry 4% of the overall sector, organised retail has a low base in India. The overwhelming majority of Indians continues to buy from friendly neighbourhood mom-and-pop stores.

Decoding the customer

But a quarter of the world's young people live in India, and more than half of Indians are below 25 years of age.

In a booming economy, that should mean a growing middle class, cheap credit and more disposable incomes. That's something, say consultants, which will make India a very attractive destination for foreigners wanting to invest in retail.

Big retail is struggling in India

The bad news is that nothing of this sort is happening: "mom-and-pop" stores are thriving and big retail, promoted by some of the top business groups in the country, is struggling.

The economic slowdown at home hasn't helped matters. Big retail footfalls have been hurt by high rents, overcrowding of malls and a credit squeeze.

Also, as a study by management consultant KPMG, external shows, Indian retailers have also made big mistakes - and the inability to compete with the neighbourhood stores is one of them.

"Mom-and-pop stores already have a model that is preferred by the consumers and is also cost efficient. The big stores are still trying to get their model right in providing an alternative to neighbourhood retailers who offer convenience, credit and personalised service," the 2009 report says.

Is it then any surprise that most Indian supermarket chains are bleeding, and some - including one with over 1,000 shops - have actually shut down?

One of the suggestions made by KPMG is that big retail needs to work harder at decoding consumer behaviour.

India is a diverse nation and a homogenous retail strategy is possibly doomed to fail.

"A case in point is discount shopping in India. Indian discount shopping is still fragmented because of diverse culture while Western retailers are able to treat the entire customer base as one. This helps them gain benefits of large-scale promotions and offers," the report says.

The report suggests that retailers should tailor discount seasons based on festivals of different regions, offer best prices and value added services (happy hours on shopping deals, offers for retirees, contests for students, for example), among other things.

The Indian consumer is a unique beast. In an article aptly titled The Myth Of Big Retail, external, journalist Sreenivasan Jain tells the story of the head of one of India's biggest retail chains explaining why his store design actually encouraged overcrowding.

"He called it his 'butt and brush' theory, a somewhat cute metaphor to describe how Indians actually prefer to shop in an overcrowded environment [where their butts can theoretically brush against each other]," he wrote.

Even this retailer is deep in the red.

Clearly, it's not going to be a cakewalk for global supermarket chains entering India. As consultants Ernst & Young warn, they need to understand local tastes, customise their product offerings and secure the right real estate to make things work.

And that will be only the beginning of the hard road ahead.