Bal Thackeray's political career

- Published

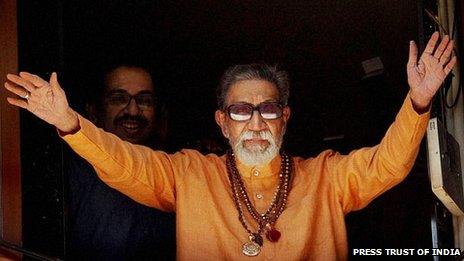

Bal Thackeray was among India's most controversial political leaders

Mumbai-based journalist and writer Sidharth Bhatia looks back at the controversial political career of Shiv Sena leader Bal Thackeray.

Bal Thackeray had a strange political journey.

He was a professional cartoonist, working in the daily Free Press Journal, who quit to launch his own movement to demand that "sons of the soil" - native speakers of Marathi, Maharashtra state's local language - be given preferential treatment in private and public sector jobs.

The Shiv Sena campaign was aimed at companies based in Mumbai, the state capital, but with much of the animus directed against south Indians who, they claimed, stole jobs from the locals.

Violence against south Indian businesses, mainly restaurants, followed and young Maharashtrian men joined up.

The Sena (or the army) was named after Shivaji, a famous Maratha king of the 17th century who had fought the invading Moghuls.

As it began building up its organisation from the grassroots level, the Shiv Sena came to be associated with violent tactics.

Attacks on political rivals, migrants, and even the media became its hallmark.

'Godfather'

A well-knit network, mainly composed of tough local youngsters, soon spread out to every neighbourhood in Mumbai.

Mr Thackeray often arbitrated disputes, got people jobs and demanded that he be consulted on all kinds of matters, including the release of films he found controversial.

Bal Thackeray's political heir is his son, Uddhav

Myths grew around him, including that he admired Hitler, which he was quoted as saying in a magazine interview that he never denied nor confirmed.

Big political success, however, eluded the party, though it began making inroads into the city's local authority, the richest civic organisation in the country.

The Shiv Sena continued to operate in the Mumbai region, including neighbouring towns, but had no reach in the rest of the state.

Political observers have long held that the ruling Congress Party did not mind it and even encouraged it initially, because it helped finish off political rivals like the Left parties.

Ayodhya riots

But after the 1980s, the Sena organisation had grown and begun aiming for power in the state and became a credible threat to the Congress.

Meanwhile, Mr Thackeray, who had now become a kind of authoritarian leader who could get things done with a mere phone call, shifted to a different stance.

He began wooing voters on the basis of right-wing Hindutva (political Hinduism) and anti-Muslim rhetoric.

In 1992, after the Babri mosque was demolished in the northern town of Ayodhya, Mumbai witnessed its worst-ever riots between Hindus and Muslims which went on for weeks.

The Sena and its cadre took full part in the rioting in which 900 people, including 575 Muslims and 275 Hindus, died and hundreds of thousands left the city never to return.

Three years later, a coalition government of the Shiv Sena and the Bharatiya Janata Party, which had also put Hindutva on its central agenda, came into power in Maharashtra to rule for the next five years.

Mr Thackeray installed one of his trusted lieutenants as the chief minister to retain, what he called, "the remote control" to run the government.

Bal Thackeray wielded enormous clout in the state of Maharashtra

In the last decade or so, its campaigns have been against north Indian migrants and religious minorities.

Mr Thackeray was a good public speaker, resorting to demagoguery and jokes to keep his audiences engaged.

His annual address in Mumbai's sprawling Shivaji Park grounds was a much-looked forward to event by his followers; this year he could not come but made a video-taped speech during which he urged his followers to give the same love and affection to his son and political heir Uddhav as they had given him.

As a cartoonist, Mr Thackeray used to profess his great love for the British cartoonist David Low whose World War II sketches became very popular.

Until recently, Mr Thackeray himself drew cartoons for his Marathi weekly, Marmik (Poignant).

For all his power, he found he could not keep his own "flock" together.

Many of his close associates deserted him as they found it difficult to move ahead in their careers.

His nephew Raj Thackeray also walked out of the home and the party because Bal Thackeray had anointed his own son as the next boss of the Shiv Sena.

'Enormous clout'

In recent days, the two sides have inched closer to each other, setting off speculation of a reconciliation, but Raj Thackeray, who resembles his uncle and is also a cartoonist, is not likely to dissolve his own party.

Bal Thackeray's chief legacy is to consolidate popular sentiment and turn it into votes, but his party will not be able to shed its reputation of using violence as a tactic.

He made no apologies for it and even bragged about it, but his son has tried to tone down the rhetoric in recent years.

The big question is - who will be the real political heir of Bal Thackeray and get the support of the Marathi speaker in the state?

Throughout the 46 years that Bal Thackeray was in public life, he neither held any political office nor stood for elections.

He was never even formally elected as the president of the political party he headed.

Yet he wielded enormous clout in the state of Maharashtra and specially in its capital, Mumbai.