How football is changing lives of Indian slum girls

- Published

&pushpa(14).jpg)

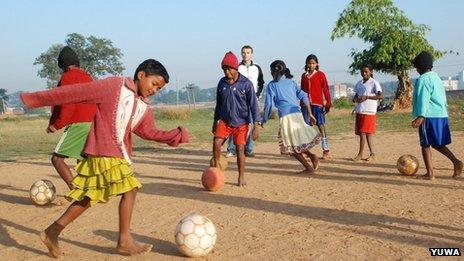

American Franz Gastler now teaches football to 250 girls from Indian slums

An American, Franz Gastler, is teaching young Indian slum girls how to improve their lives through the game of football. Monica Sarkar reports from Mumbai.

Mr Gastler, 30, is from a middle-class family in Edina, Minnesota, but for the moment, he has swapped his comforts for the dust and grime of Indian slums.

He divides his time between Ranchi, the capital of the eastern state of Jharkhand, and the western city of Mumbai.

A graduate of Boston University, he joined a non-governmental organisation in 2008 which brought him to Jharkhand.

The state is one of the poorest in India, external with one of the highest rates of illiteracy, child mortality and malnutrition.

Extraordinary life

Softly spoken, simply dressed, with blonde hair and blue eyes that stand out a mile in India, Mr Gastler has chosen an extraordinary life.

While working for the NGO where he taught English to children, a young girl asked him to teach her football.

He agreed, and in 2009, he co-founded Yuwa - youth in Hindi - with three American friends, using their hard-earned wages to finance the football teaching initiative.

While his friends continue to work full-time at their jobs, Mr Gastler is dedicated to Yuwa.

In Mumbai, Franz Gastler sleeps on the hard floor of a small room in a slum

For the last two years, he has been living in a building called the Yuwa House in Ranchi - which serves as a community centre and basic accommodation for Yuwa volunteers.

Football practice takes place on three fields, all within 10km (6.2 miles) from the house.

While growing up, Mr Gastler played ice hockey, judo and enjoyed skiing, but until coming to Jharkhand, he had never kicked a football. In fact, he had not even watched a football match until recently.

But his decision to leave his job and teach five to 17-year-old girls football has helped improve their lives and avoid being married off at an early age.

Initially, 15 girls came forward to join his first team. Today, around 250 girls practice daily, three of whom are on the national girls' team and have played outside the country.

Game changer

In 2011, Yuwa won a Nike Game Changers' award of $25,000 (£15,539).

This led to a partnership with a Mumbai-based travel agency and Yuwa began working in Dharavi - one of the largest slums in Asia, external - with new girls from the slum joining football coaching.

3.jpg)

Shivani was selected for India's Under-13 national team

Funds have been raised to run the Mumbai programme for two years and Mr Gastler visits the city from Jharkhand every couple of months.

In Mumbai, he sleeps on the hard floor of a small room in the slum with a friend.

"You get attacked in the night by biting ants and cockroaches running around," he yawns and smiles as he tells me his story.

Mr Gastler speaks clearly in Hindi with the girls and their families.

Practice begins in the early hours on a dusty and uneven Mahim Ground next to the slum, with fun games to warm up before play.

"The way our programme goes is that the girls make their own rules. In Jharkhand, the girls find their own ground, plan the schedules and practice everyday," he says.

He says this way of training encourages them to be team leaders - peer pressure is important at their age, so they tend to listen to one another.

"Before, I used to fight a lot with people. But now, I've learned to help others," says 16-year-old Sunita.

According to Mr Gastler, the girls take the initiative to make the Yuwa programme work for them.

At first it was difficult for their parents to understand or accept an activity that is uncommon for girls. It took time for them to appreciate their daughter's focus and growing independence, he says.

"The girls don't get much pocket money; parents invest everything in their boys. So the girls pretended they needed money for school supplies and sweets."

"But eventually, some parents became pretty impressed," he says.

'Under-promise, over-deliver'

Yuwa also supports the girls emotionally and off the field.

Kusum, 14, another girl from Jharkhand says she used to "live carelessly with torn and dirty clothes" but now she has learned how to stay clean.

The girls wake up early and help their mothers with household chores and attend school before practice

Mr Gastler says that in working with the girls, he has learnt to "under-promise and over-deliver" because village girls are used to working hard and achieving minimal results.

All the girls wake up early, help their mothers with cooking and household chores and attend school before practice.

"Of the first 15 girls who came on the football field, many of their older sisters were married off at ages 13 to 15," says Mr Gastler. "But only one girl out of the whole football group has now been married off at 15."

"This is exciting; I enjoy it a lot. Even though it's not financially rewarding, it's much more satisfying than making money," he says.

Thirteen-year-old Shivani says her father encouraged her to play.

He died last year from diabetes but before his death, he told her that she would play for India one day.

A few months later, she was selected for the India girls' Under-13 national team and was part of the final 18 who travelled to Sri Lanka.

Shivani says she only wants to play football.

When asked if she thinks she will earn enough, she thoughtfully nods her head. But her expression says money is not the reason why she plays.

- Published14 November 2012

- Published21 February 2012

- Published24 September 2012

- Published30 June 2012