Family of gang rape accused 'made infamous' in home village

- Published

The family of the young man cannot be identified for legal reasons

A court in India has ruled that one of the six people accused of the gang rape and murder of a 23-year-old woman in Delhi last month is a minor. BBC Hindi's Shalu Yadav visited the village of this 17-year-old juvenile at the centre of a case that has shocked India.

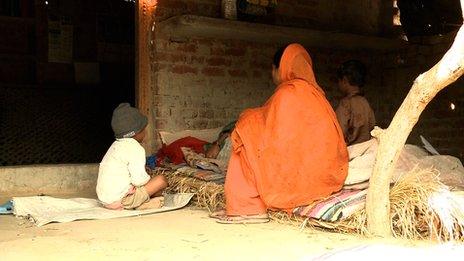

Miles away from India's capital, Delhi, villagers have gathered around a small house of mud and hay.

Inside, a sick woman lies on a makeshift bed on the mud floor.

She is unable to move and lets out cries of pain. Her five children try to comfort her as she shivers.

"She hasn't been well since she heard the news about her eldest son," says her daughter.

She had thought him dead until police came knocking on her door last month and told her he was one of the accused in the brutal gang rape case.

"There weren't many job opportunities in the village. At the age of 11, he asked for my permission to move to Delhi for a job. We last spoke to each other just before he boarded the bus to the city. He told me to take care of myself and not to worry about him," says the distraught mother who cannot be named for legal reasons.

Shattered hopes

The family of seven is possibly the poorest in the village. The father is mentally disabled and cannot take care of the children, say the villagers.

Their only income comes from the two teenage daughters in the family, who work all day in the field to earn $2 (£1.30) a day.

"My sister and I don't have a permanent job. We are called by the field owners to work in their fields. But that doesn't happen every day," says one of the daughters.

The family's hopes of a better life lie with a lean buffalo they bought with a neighbour

There are two rooms in the house, one of which is reserved to the lean buffalo they bought with a neighbour.

"We are waiting for the day she is fit enough to produce milk. We can then sell her for a good price. Till then, feeding her is a challenge as we ourselves don't get regular meals," says the daughter.

The mother says the family has not had a proper meal for the last two days.

"I sent my eldest son to work in Delhi, in the hope that he would earn well and bring us out of poverty. But that hope was short-lived. He sent us money for a few years and then disappeared. I was angry with him and later thought he was dead."

She can hardly recollect how he looks and struggles to describe him. But she insists he was a docile boy and could not commit such a heinous crime.

"The news made me angry, but I was heart-broken as well. I couldn't believe what the police told me. He was a very sensitive child and would be scared to confront anybody in the village. I'm sure he fell into bad company in Delhi and was led into committing this shameful act," she says, teary-eyed.

"I'm not sure if I can forgive him. If he has committed this crime, he should be given a harsh punishment. He made us infamous in the entire village. My heart sinks when I think about the future of my daughters. Who will marry them now?"

She says she has decided against sending her other three sons to Delhi as a result of the incident.

Big-city dreams

Millions of children in India migrate from villages to cities every year, in search of job opportunities.

Campaigners say poor migrant children live without any emotional support and some of them often become involved in criminal activities.

The accused juvenile in the gang rape case, having left his village at the age of 11, lived his formative years alone, doing menial jobs in Delhi.

His crime has sparked a debate across India about juvenile laws, which call for a lesser punishment for youths under 18 years of age.

The court may have pronounced him a juvenile, based on the documents from his school, but the school headmaster in the village is not sure whether he is actually a minor.

"We can't really be sure of his age, but according to the school admission records, he is 17 years and six months. He could be older than this, but he is not younger for sure."

He says the admission process in India's villages is often basic.

"In villages, parents bring their children to the school for admission, without any certificate that confirms the child's age. We just have to trust the parents with the age of the child and admit him/her to the school," says the headmaster, who cannot be named for legal reasons.

For the accused's siblings though, the immediate concern is finding a proper meal rather than worrying about their brother, who they do not even remember growing up with.

The youngest in the family looks out and waits for his eldest sister to come back.

"I'm very hungry. If my sister brings money, we will have our next meal and mother can possibly afford a doctor as well."