Is India's food security bill the magic pill?

- Published

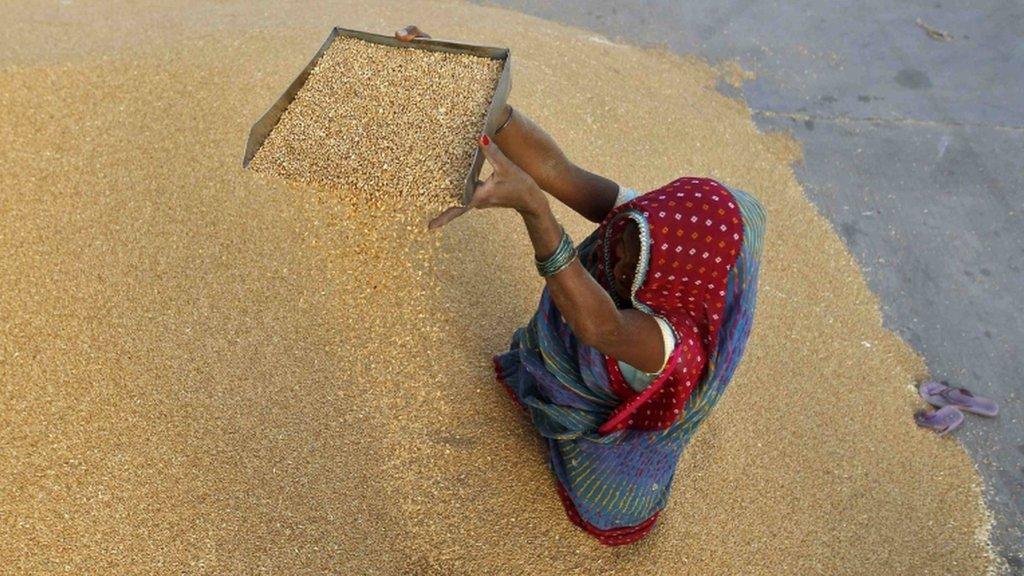

About half of all Indian children are estimated to be undernourished

Despite robust economic growth and rising incomes, India remains a hungry republic.

It ranks 65 out of 79 countries on the Global Hunger Index , externalfrom the International Food Policy Research Institute. By the government's own estimate, external, nearly half of India's children under five are chronically malnourished. From 2005-2010, India ranked second to last among 129 countries, external on underweight children, below Ethiopia, Niger, Nepal and Bangladesh.

Surveys a decade ago found that 36% of Indian women of childbearing age were underweight, compared to 16% in 23 Sub-Saharan countries.

Economists Amartya Sen and Jean Dreze have called India's inability to properly feed its women and children "catastrophic failures, with wide-ranging implications not only for the people of India today but also for the generations to be born in the near future".

The landmark Food Security Bill, external, the Congress-party led government belives, is India's best shot at battling chronic malnutrition and hunger.

The bill - which was passed by ordinance but needs to be ratified by parliament - proposes to make food a legal right. It seeks to cover two-thirds of the country's population and provide 5kg of subsidised food grain per person per month.

India needs 60 million tonnes of food a year to service the scheme

The bill also proposes free meals and maternity benefits for pregnant women, lactating mothers, children between the ages of six months and 14 years, and malnourished children and destitute and homeless people.

All this should be good news for India, except that many don't believe so.

For one, some critics argue that the scheme could upset the budget with subsidies on food doubling to a whopping $23bn (£15.5bn)., external This will not help India, they say, to cut its fiscal deficit to 4.1% of GDP by 2012-2013 from an uncomfortable 5.5% expected this fiscal year.

These critics frame India's food security debate as one of a "question of hungry people versus fiscal responsibility".

But there are some graver reservations over the scheme, which its critics say have not been addressed.

One is that it is proposed the food be distributed through India's notoriously corrupt and leaky state-owned cheap food ration shops.

Various studies over the years have estimated that anything between 37% and 55% of the subsidised rice and wheat are illegally diverted from these shops and sold in the open market. Using these shops to distribute more food, they say, will mean more pilfering and more corruption.

Then there is the issue of identifying the beneficiaries.

The scheme classifies two categories of beneficiaries, who shall be identified by the federal government and the states.

Activists like Binayak Sen argue that the process of classifying beneficiaries is complex, external and would, also, lead to corruption.

Then there's the question of the shambolic quality of storage of food in India.

By one estimate, India needs 60 million tonnes of food stocks, external to service the plan. India's actual food stocks could be more than 90 million tonnes this year.

A lot of the food actually rots in decrepit warehouses and in open space, something which Jean Dreze and Amartya Sen describe as a "scandalous phenomenon", a "situation of hunger amidst plenty".

Critics say this primarily happens because of the government's warped food policy: the government buys food grain at unreasonably high prices (called the "minimum support price") from farmers which bolsters production, but lowers consumer demand because of the high price of food. The government is then forced to buy the difference to sustain the artificially high prices.

One critic I spoke to said the bill was an "example of bog-standard populism" of the ruling government with an eye on what promises to be closely fought general elections in 2014.

They point out that many Indian states are already providing cheap food to the majority of their people, and yet many of them continue to have high rates of malnutrition.

Some, like Columbia University economist Arvind Panagariya, even reject the claim that India suffers from worse levels of malnutrition than poorer sub-Saharan Africa, external, arguing that a flawed WHO methodology is to blame. Others, like economist Jayati Ghosh, say the bill is not enough as it does not provide universal access., external

"In the end," one economist tells me, "it's not really a question of whether the bill will add to India's soaring subsidy bill. The government can easily cut other subsidies in fuel and fertiliser that end up benefiting the well-to-do.

"It's about the quality of the delivery system and to ensure that the food reaches the beneficiaries."

One way out, say many, is to transfer cash to the beneficiary instead of delivering food through a creaky, graft-prone distribution system.

Clearly, the jury is still out, external on how to tackle hunger in India - and the Food Security Bill may not the magic pill that the government thinks it will be.

- Published3 July 2013