BJP's big risk on Narendra Modi

- Published

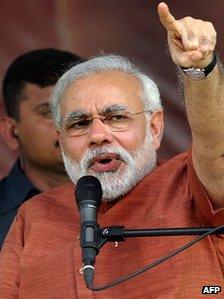

Modi has won four terms as Gujarat chief minister

Narendra Modi is one of the canniest Indian politicians.

Hours after he had been named as the prime ministerial candidate for the main opposition Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) for next year's general election, his flashy website welcome had duly been updated.

"Thank you! Let us work together to make Mission 272+ a reality," the new slogan said, replacing India First, the moniker of his muscular nationalist campaign.

Mission 272+ alludes to the number of seats in parliament the party needs to win for an absolute majority, a miracle for any party in India's severely fractured politics.

In the background, a beaming Mr Modi flashes a victory sign.

He has tried hard to reinvent himself, from the somewhat remote chief minister of Gujarat who steadfastly refused to apologise for the 2002 religious riots that killed more than 1,000 people, to a sprightly, energetic leader who appeals to a rising tide of young voters.

At 62, he's comparatively young by Indian political standards. People in Gujarat have backed him enthusiastically for four successive terms, impressed by his reputation as a no-nonsense administrator. The jury is still out on whether Gujarat's enviable record of development has been truly inclusive.

Mr Modi has been clever enough to retool his image to appeal to India's young. He talks about an India that has changed from a "nation of snake charmers to a nation of mouse charmers", referring to its info-tech success.

He says he "sows dreams in the eye of my fellow-citizens".

Closely fought

On Twitter, he exhorts the young to register to vote because they are the "power and strength of India".

However, Mr Modi continues to remain a hugely divisive and polarising figure. One key ally of the BJP-led coalition quit after fears that supporting him could lose Muslim votes.

Some 15% (180 million) of India's 1.2 billion people are Muslims. They comprise over 11% of the voters in six states, including the politically crucial state of Uttar Pradesh. It is unlikely that they will warm to Mr Modi.

Many people believe that by making the 2014 election a presidential-style referendum on Mr Modi, the Hindu nationalist BJP is taking a huge risk.

For the past two decades, elections in the world's largest democracy have been closely fought affairs, with regional aspirations, local issues, caste dynasts and local chieftains playing a crucial role.

In the end, the parties with the bigger numbers and common interests cobble together a ruling coalition.

The BJP hopes that Mr Modi, taking advantage of a ruling Congress party that is tired and enfeebled, will attract enough votes to sweep the party into power.