Why do many India MPs have criminal records?

- Published

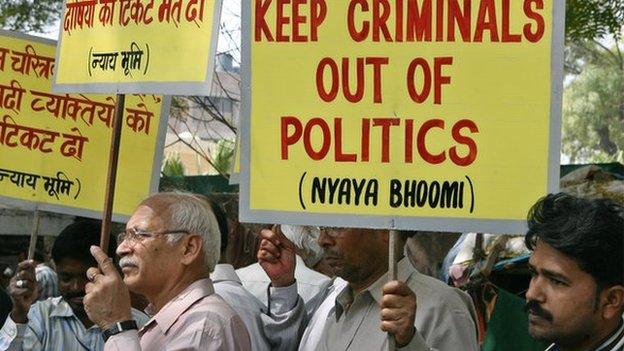

A third of the current members of parliament have criminal cases pending against them

"We need to build a consensus on how to prevent individuals with a criminal record from contesting elections."

A necessary, even obvious fundamental you would think of building the world's largest democracy.

And when Sonia Gandhi, India's most powerful politician, uttered those words three years ago,, external even her main opponent, the leader of the BJP agreed.

Yet since then, things have gone in the opposite direction - with more alleged lawbreakers among India's lawmakers than ever, a third of the current parliament according to a watchdog called the Association for Democratic Reforms. , external

By some calculations, politicians with a criminal record are more likely to be elected than those with a clean slate - because, says the ADR, they have more illicit funds with which to buy votes.

And on Tuesday night, India's cabinet sought to ensure there was even less chance of criminal politicians facing their own laws.

It issued an order overturning a Supreme Court ruling demanding the disqualification of any politician convicted for crimes punishable with more than two years in jail.

This was "to ensure that governance is not adversely impacted, external", the government had argued, with no apparent irony intended.

Unusual speed

Arguably, of course, the government is right. Losing tainted local or national politicians - among them many accused murderers, rapists and fraudsters - could upset delicate political alliances and make it even harder to get laws passed.

So often derided for doing nothing, this time round the cabinet acted with unusual speed.

The urgency it appears is the impending conclusion of two cases involving key politicians, due before Prime Minister Manmohan Singh gets back to India from a trip to the US.

There's been some criticism of criminal politicians

One concerns Lalu Prasad Yadav, a former railways minister and Congress party ally, charged with pocketing millions of dollars in subsidies for non-existent livestock.

Another concerns Congress MP Rashid Masood, already convicted of corruption and due to be sentenced next week. When the BBC asked his office for a comment, his assistant told us "he is unwell".

"Don't know whether to laugh or cry" tweeted MP Baijayant Panda in response to the government's protective move.

He is a rare voice though inside the chamber campaigning against criminals sitting alongside him.

There's been some other criticism outside, but not much. Indians have become very used to these kinds of shenanigans.

Almost forgotten already are calls in the Verma commission report, external into the December 16 Delhi gang rape case for all politicians accused of sexual crimes to be barred from office. Instead, six politicians charged with rape remain in office.

The opposition BJP has said it will oppose the cabinet order. But its record is just as murky, with even more accused criminals among its elected members in parliament and state assemblies than the Congress.

And with elections round the corner, none of the parties want to risk real reform right now, whatever they have signed up to in the past.

The world's largest democracy is not alone in allowing so many questionable people to run it. Fellow Brics member Brazil has similar numbers of alleged criminals running the country, external.

The difference though is that in Brazil, brazen political abuses have provoked major protest.

But, says Indian MP Baijayant Panda: "This is a phase all democracies have gone through - look at the US."

Voters will start to demand change, he predicts: "This is the last era of brazenness."

- Published25 January 2013

- Published3 August 2012