India's puppeteers struggle to survive

- Published

Delhi's traditional puppeteers worry that slum redevelopment will threaten their way of life.

As the authorities plan to relocate a colony of puppet makers in the Indian capital, Delhi, its few thousand residents tell BBC's Akanksha Saxena why life is a daily struggle for them.

Puppetry and magic have been popular forms of traditional entertainment in India for long, but in recent years, the puppeteers have been desperately trying to preserve their dying art form.

About 3,000 puppeteers live with their families in Delhi's Kathputli (puppet) colony.

Situated on the cusp of old and new India, the slum is surrounded by a flourishing vision of modernity - there is a Metro rail station nearby, a milk dairy plant and a super speciality hospital.

But now a private real-estate developer has won the bid to make an upscale residential complex and a shopping mall on this land worth billions of rupees and the puppet makers have been told they will have to move.

One can almost miss the narrow lane going into the slum but the sound of the drum beats cannot go unheard.

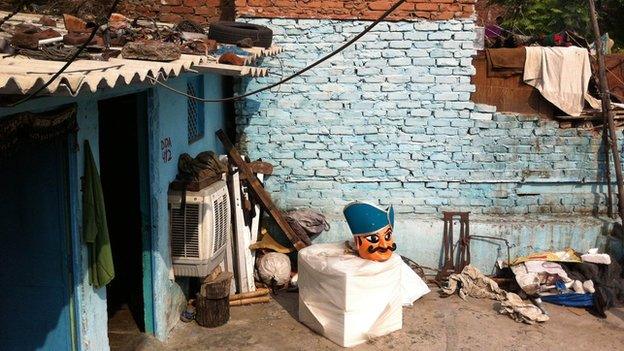

The place is a haphazard mess of cramped houses with illegal electricity connections and water supply, open sewage drains and children playing barefoot in the narrow lanes.

'Magical'

But this slum is also home to some extraordinary artistic talent.

"Our ancestors were travelling artists. They found work and settled here. Several artists live here. They are puppeteers, magicians, folk singers, painters, dancers, acrobats, jugglers and storytellers. It's rare to find all this in one place. This place is magical," says Puran Bhat, a traditional puppeteer who has been living here for the past 50 years.

About 3,000 puppeteers live with their families in Delhi's Kathputli (puppet) colony, but they have been told they will have to move out now

The place is a haphazard mess of cramped houses with illegal electricity connections and water supply, open sewage drains and children playing barefoot in the narrow lanes.

Many puppeteers are choosing to leave the profession as they find it difficult to make ends meet.

The colony residents have been promised rehabilitation to one-room tenements, but most feel that they will be left in the lurch.

"Instead of moving us, the government should turn our colony into a tourist destination for people to come and experience our world. We perform for foreign diplomats and visitors, we represent India's culture but when it comes to our welfare, the authorities ignore us. We are valued more abroad than in India. No one knows this colony in Delhi; it is not even on the map," Mr Bhat says.

The colony residents come from across the country and belong to different castes.

At a stage performance with synchronised lights and folk music, Mr Bhat and his group stage a popular folk tale called Amar Singh Rathore ki kahani (The story of Amar Singh Rathore) which leaves the audience spellbound.

Wide-eyed children try to grasp how puppets - inanimate objects - can talk, dance and behave like humans.

"It is a great way of storytelling and their colourful costumes are a big draw for children up to 10 years, they really enjoy it," says school teacher Geeta Sharma.

Vanishing act?

But everyone agrees that the ancient art of puppet theatre is in rapid decline now. It has been facing stiff competition from cinema, television, video and computers and today there are few takers for live puppet shows.

Mr Bhat says there is little money in working with puppets and many artists are choosing to leave the profession as they find it difficult to make ends meet.

But the ancient art of puppet theatre has been rapidly declining in recent years.

Puppeteer Puran Bhat says there is little money in working with puppets now

It has been facing stiff competition from cinema, television, video and computers and today there are few takers for live puppet shows.

However, some young volunteers like college student Swayan are trying to keep puppetry relevant by trying to improve their outreach and find new avenues for puppetry in the mainstream.

"We went to a few schools and children were interested in the show about bullying. It helps them understand the problem better," Swayan says.

A young puppeteer in Mr Bhat's group, Sarjoo hopes to revive the art of puppetry.

"We are young, we can pick up any other occupation to survive, but we will try hard and will not let the traditional puppetry die; we will take it forward and make it reach the pinnacle of the art world," he says.

It is a sentiment echoed by some other young artists in the colony.

But in the face of poverty and desperation, and disenchantment of people from traditional arts, the vanishing act could be approaching soon.