A spectacular debut by a new Indian party

- Published

The new party showed a lot of imagination, say experts

India's political waters are stirring after a long time.

A pugnacious outlier called the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) or Common Man's Party, born out of a strong anti-corruption movement and tapping into popular disenchantment with the major political parties, has made a spectacular debut in state elections in Delhi.

It has picked up 28 of the 70 seats, external and more importantly, over 30% of the votes, routing the ruling Congress party and putting the single largest BJP party under watch. Thanks to the AAP's bravura performance, the capital may be headed for a hung assembly, external and forced into a re-election. "AAP proves," an analyst told me, "the people are desperately looking for alternatives, not merely an option."

Even its critics concede the Delhi result is a stunning feat for a year-old party in a country where barriers to political entry are prohibitively high.

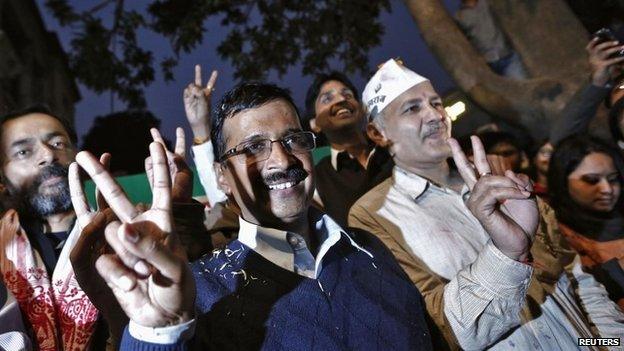

Arvind Kejriwal, a once-taciturn civil servant-turned popular leader, has emerged as the giant killer, external, routing Chief Minister Sheila Dixit, a veteran Congresswoman, who was eyeing a fourth consecutive term in office. Not since the emergence of the regional Telugu Desam Party in southern Andhra Pradesh state in the 1980s has India seen such a striking political debut.

Credible alternative

Analysts say the AAP has offered itself as a credible alternative to people fed up with corruption, unresponsive politicians and high inflation.

They believe that the party changed the political discourse of the elections. It forced the BJP to change a lacklustre chief ministerial candidate, put out separate manifestos for 70 constituencies, skilfully used social media, successfully garnered the support of the traditional media and promised to pursue "honest, people's politics". It also radically altered the debate on the blight of corruption. The new party projected itself as "pro-change, anti-establishment and anti-politician", as an analyst succinctly put it.

Arvind Kejriwal has emerged as a 'giant killer', defeating Chief Minister Sheila Dixit

However, the AAP's emergence also points to an inflection point in India's stodgy politics dominated by identity, caste, patronage, sycophancy, dynastic impulses and opaque financing.

What makes the party unique?

For one, unlike new parties in the past that had their origins in region and identity-based movements, AAP was not identifiable with either.

Also, it is the first party to emerge entirely out of urban India with its leaders mainly belonging to the middle class. "The party," analyst Pratap Bhanu Mehta told me, "is the creation of urban, middle class imagination."

Moreover, AAP is the first party that has impressed with an innovative use of political techniques. It was clearly demonstrated in its poll spending model - transparent, open donations from the public - and volunteer workers who took time off from their jobs and businesses to work for the party.

Though born out of a vigorous anti-corruption movement that captured the people's imagination, the party's identity is forged around the notions of accountability and governance, something unprecedented in India's parties.

The party is also forcing other parties to rethink their strategies.

"They showed a lot of creativity and imagination. They took risks - the act of Mr Kejriwal taking on Sheila Dixit, for example. The AAP thought out of the box," says Mr Mehta.

Will the party now capitalise on its sterling performance in the capital and go national?

Historians like Dipankar Gupta feel that the party should entrench itself locally - by contesting municipal elections, for example - before venturing to the national stage. "It should play within its limits," he says.

'Changing the system'

But Mr Kejriwal's party clearly has other ideas: senior leaders tell me that they have opened more than 300 offices all over India and the party plans to contest next year's general elections "wherever we stand a chance".

It believes its time has come and it has to capture the zeitgeist: many believe most cities and states have a substantial population of floating voters who are now desperate for credible alternatives.

But can Mr Kejriwal's party replicate its success outside of Delhi?

The AAP used the broom as its election symbol

Politics is the art of the possible. Many believe that to become successful outside India's most urbanised state, the AAP will need to forge tactical alliances in India's fractious and complex politics. Will Mr Kejriwal's party do that? How will it navigate challenges of language and local contexts in an dizzyingly diverse country and build local networks? (The party is largely seen as a Delhi-centric phenomenon, and most of its existing leadership hail from the city.) Or will it, like other parties, easily become a prisoner of India's politics and bureaucracy? Will Mr Kejriwal, its charismatic leader, end up fostering a cult of personality, a bane of India's political parties? Will it be able to marry its idealism and pragmatism?

AAP activists are fond of saying that they are not in politics "mainly to seize power but to change a compromised and corrupt political system".

But changing a system in a country of high aspirations and fraying institutions requires the party to participate and work it from within. The outlier needs to become the insider. There are questions over the party's institutional proposals. The AAP's manifesto, external is a mixed bag of promises ranging from participatory decision making to cheap electricity and free water.

More seriously, many say, the AAP's rising is a loud and clear warning to India's political parties to return to their ideological moorings, be imaginative, engage in a battle of ideas and begin a conversation with people fed up of their grandstanding and rabble rousing.

"I am not sure Delhi's people voted for an alternative party in the strictest sense. It was more a vote in anger and protest against the existing parties and how they have been conducting themselves," says analyst Mohan Guruswamy.

If India's main parties don't change, the Common Man's Party could become a formidable national political force faster than many would imagine.

- Published8 December 2013