How life is improving in India's poorest regions

- Published

.jpg)

The free mid-day meal programme is reaching India's poorest villages

A survey done earlier this year shows that public facilities in the poorest regions of India have steadily expanded, improving the lives of people there, writes development economist Jean Dreze.

Once upon a time, not so long ago, public facilities in the poorest districts of India were few and far between.

Most people were left to their own devices and they lived in the shadow of hunger, insecurity and exploitation, with no public support in their hour of need.

Many villages had no school, no health centre, no ration shop, no approach road, no post office, no telephone, no electricity, and perhaps even no convenient source of drinking water. Where an anganwadi (government sponsored mother and child-care centre) existed at all, it was often closed. There were no public works around, and no pensions for widows or the elderly.

It takes a pause to realise that all this really applied "not so long ago" - as recently, say, as the mid-1990s, when living conditions in the country's poorest districts were vividly evoked by journalist P Sainath in his book Everybody Loves a Good Drought.

To claim that the situation has radically changed would be a serious delusion. Yet, the picture today is very different from what it used to be.

Not only have public facilities steadily expanded, people are also forming new expectations of them and demanding more.

Slowly - much too slowly - but surely, the principle of social responsibility for people's basic needs is taking root.

'Quiet progress'

During the last 10 years, student volunteers have been conducting regular field surveys in various parts of the country, sometimes looking at schools or health centres, sometimes at the rural employment guarantee scheme, external or the public distribution system.

Over time, we have seen a great deal of change, often - not always - for the better.

The ground realities, at any rate, are strikingly different from the picture of doom and gloom that emerges from the mainstream media.

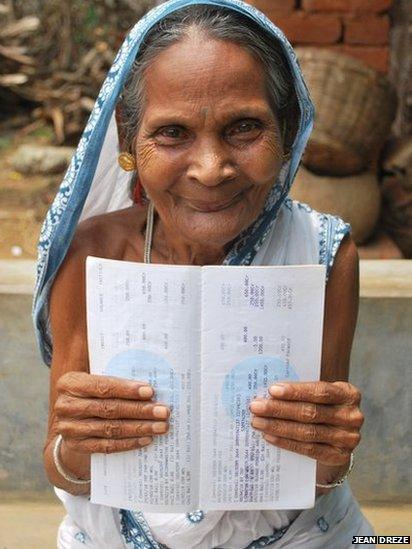

The monthly pension is a lifeline for widows

It is a good thing, of course, that the media swiftly blows the whistle when things go wrong. But what tends to be lost in this stream of "drain inspector's reports" is the quiet progress that many states are making in providing essential facilities to their citizens.

The last in the series of field surveys, nicknamed Public Evaluation of Entitlement Programmes (Peep), external, took place in May-June 2013.

This survey, initiated by the Indian Institute of Technology in Delhi, was conducted in 10 states: Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Orissa, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu and Uttar Pradesh.

In each state, the survey focused on two of the poorest districts and covered five entitlement programmes: the Integrated Child Development Services, external, mid-day meals, the public distribution system, external, the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act and social security pensions.

One of the districts covered by the survey is Surguja in Chhattisgarh, an area I have visited at regular intervals during the last 12 years.

When I first went there to assess development programmes, in 2001, I was barely able to identify a few "islands of relative success in a sea of inefficiency, corruption and exploitation".

Most villages were deprived of basic facilities such as a decent approach road, a ration shop, or electricity.

Today, these facilities are expected as a matter of course.

Most villages in Surguja have a well-functioning ration shop where an average family gets 35kg of rice every month at a symbolic price.

Most families also have a "Job Card", and are able to get some employment on local public works under the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act.

Most children go to school, where they get a reasonably good meal on the house. Many widows and elderly people get a small but valuable pension.

It is not Sweden or Canada, but still, these entitlements add up to something worthwhile, and looking ahead, one begins to see the possible foundations of a social security system.

'Startling variety'

Not every poor district, of course, has done as well as Surguja.

Even within Chhattisgarh, there are areas - particularly in the south - where the state is better known in the fearful guise of a forest guard or police officer than that of a smiling anganwadi worker.

Looking across the country, there is a startling variety.

.jpg)

The jobs guarantee scheme is a success in many of the poorest districts of Bihar

The low quality of grain served to the poor remains a concern

Some states, like Tamil Nadu, have a good record of efficient and equitable public services across the board. Others, like Uttar Pradesh, are incorrigible offenders.

Most are somewhere in between - improving in some fields, stagnating or even regressing in others.

Behind this variety, however, there is an important pattern: states reap as they sow, in the sense that serious efforts to make things work often produce results.

Even states with an embarrassing reputation for corruption and misgovernance, like Orissa - or Chhattisgarh for that matter - have shown that change is possible. Recent experience also shows that it is mainly through democratic struggle that advances have been made.

Needless to say, there is still an enormous way to go in meeting people's basic constitutional rights.

For instance, while it is certainly a good thing that children - girls and boys - are now flocking to schools across the country, the quality of school education remains abysmal.

Similarly, the coverage of vaccination programmes has greatly expanded in recent years, but India is still way behind Bangladesh in this respect.

If the survey brings a ray of hope, it lies in further evidence that public services do improve - often at unexpected speed - with adequate resources, political support and application of mind.

Conversely, the penalties of neglect can be severe, as the recent decline of the rural employment guarantee scheme illustrates.

Further democratic struggle is the only way to ensure that positive trends have the upper hand.

Prominent scholar and economist Jean Dreze is a naturalised Indian of Belgian origin

- Published2 August 2013

- Published24 July 2013

- Published20 March 2012

- Published22 March 2013