Siachen dispute: India and Pakistan’s glacial fight

- Published

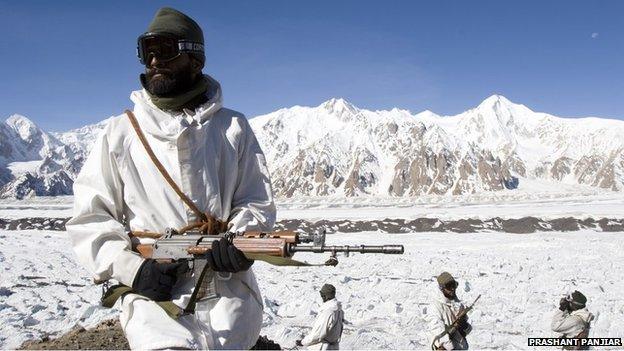

Indian troops on the Siachen - the world's first "oropolitical" conflict

On 13 April 1984, Indian troops snatched control of the Siachen glacier in northern Kashmir, narrowly beating Pakistan. Thirty years later, the two sides remain locked in a stand-off, but the Indian army mountaineer who inspired the operation says his country must hang on whatever the cost.

Virtually hidden from public view, the world's highest conflict is moving into its fourth decade.

The struggle between India and Pakistan over the Siachen glacier has even spawned a new term: "oropolitics", or mountaineering with a political goal.

The word is derived from the Greek for mountain, and Indian army colonel Narendra Kumar can justly claim to be the modern father of oropolitics because his pioneering explorations paved the way for India to take the glacier in early 1984.

But what started as a battle with crampons and climbing rope has turned into high-altitude trench warfare, with the two rival armies frozen - often literally - in pretty much the same positions as 30 years ago.

Shocking waste

The vast majority of the estimated 2,700 Indian and Pakistani troop deaths have not been due to combat but avalanches, exposure and altitude sickness caused by the thin, oxygen-depleted air.

"It's been a shocking waste of men and money", says a former senior Indian army officer and Siachen veteran.

"A struggle of two bald men over a comb" is the verdict of Stephen Cohen, a US specialist on South Asia, dismissing the Siachen as "not militarily important".

This would perhaps be comforting if the two combatants did not both have nuclear weapons.

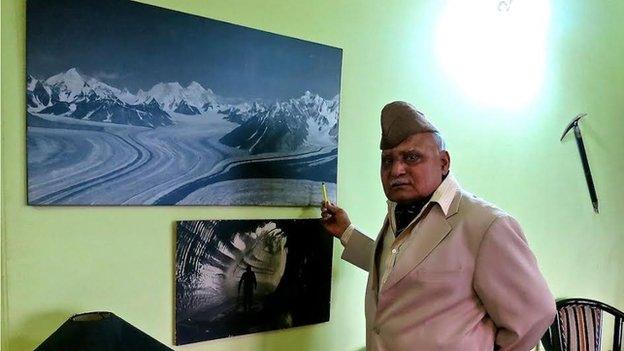

Surrounded by photographs and memorabilia of his climbing exploits, Col Kumar, now in his 80s, says the struggle was critical to preventing Pakistani encroachment into northern Kashmir.

Col Kumar's maps helped Indian troops take control of the glacier

As with so many long-running conflicts, it began with an undefined border.

In the late 1970s, a German mountaineer showed Col Kumar a US-drawn map of northern Kashmir marking the Indian-Pakistan ceasefire line much further to the east than he expected. It appeared the Americans had cartographically ceded a large chunk of the eastern Karakoram to Pakistan, including the Siachen glacier.

"I bought the German's map and sent it straight to the director general of military operations," says Col Kumar, then in charge of the Indian army's mountain warfare school. "I said I would organise an expedition to the area to correct the map!"

But despite several ceasefire agreements, India and Pakistan have never officially demarcated the "line of control" in the extreme north of Kashmir, including the Siachen. And both sides publish different maps depicting their version of the geography.

With its ally China to the north, Pakistan was first to see the potential for oropolitics in this strategic vacuum.

Throughout the 1970s, it gave permits to foreign mountaineers to climb around the glacier, fostering the impression this was Pakistani territory - until Col Kumar sounded the alarm.

The extreme conditions are the biggest problem for soldiers on the Siachen glacier

But when he got permission for a counter-expedition in 1978, it quickly leaked across the border. "As we reached the Siachen, Pakistani helicopters were flying over us," Col Kumar smiled, "and they were firing out coloured smoke."

This and rubbish left by previous climbing teams convinced him the Pakistanis were stealthily taking over.

But at first, he complains, Indian generals would not take him seriously. Then in early 1981, Col Kumar was given the go-ahead to map the entire glacier, all the way to the Chinese border.

This time there were no leaks. And the following year he wrote up his expedition in a mountaineering magazine, in effect staking India's claim.

With the Indian army now clearly involved, the Pakistanis were determined to entrench their claim. They might have succeeded if Indian intelligence had not learned of some interesting shopping in the UK in early 1984.

An Indian army mountaineer on Indira Col above Siachen glacier in 1981

"We came to know the Pakistanis were buying lots of specialist mountain clothing in London," grins Col Kumar. A retired Pakistani colonel later admitted they had blundered by using the same store as the Indians.

India immediately dispatched troops to the Siachen, beating Pakistan by a week. By then they had already got control of the glacier and the adjacent Saltoro ridge, using Col Kumar's maps. One of the key Indian installations on the Siachen today is named Kumar Base after him.

A Pakistani counter-attack led by a Brig Gen Pervez Musharraf a few years later was one of several that failed to dislodge the Indians. Since a ceasefire deal in 2003, the Pakistanis have given up trying.

But though both sides are now better at coping with the extreme environment, it still claims the lives of dozens of soldiers each year.

Because it occupies the harder-to-supply higher ground, India pays the heaviest financial price, currently estimated to be around $1m (£600,000) a day.

"With all the money we have spent in Siachen, we could have provided clean water and electricity to half the country," says the former Indian army officer.

Both armies, he says, ensure their "heroic narratives" of the conflict dominate by limiting media access to the Siachen.

Any hints of a thaw, most recently when Pakistan lost 140 soldiers in an avalanche, have always faded away.

The Siachen is just the coldest of several fronts in the frozen conflict over Kashmir, with neither India or Pakistan prepared to take the first step.

"There will be no movement on Siachen until there's movement on everything else," predicts a former senior Indian intelligence officer.

In the meantime, Col Kumar says India should be consolidating its position on the Siachen, by allowing more foreign mountaineers to climb there.