Political battle for India's city of faith

- Published

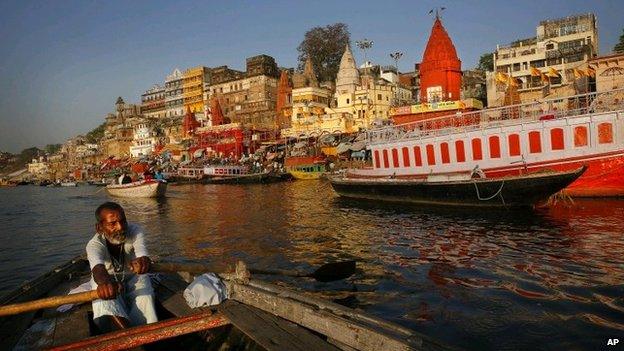

Activists of all stripes have been making their presence felt in Varanasi

"Let us revive the Ganges, let us build a new Varanasi," Narendra Modi, the man who many believe will be India's next prime minister, tells a public meeting on the outskirts of Varanasi.

Mr Modi, the BJP's candidate for the ancient city, is pushing the right buttons.

Varanasi is on the verge of civic ruin - potholed roads, gridlocked traffic, choked drains, mountains of garbage, scarce water, and most worryingly, a filthy and polluted Ganges that runs through it and where thousands of pilgrims come to take a dip.

Three sewage treatment plants can treat only a third of the detritus that flow into the river through 33 drains every day. The water is contaminated with faecal coliform bacteria - tests show it's some 800 times more than the permissible limit for bathing. A 141km (87 mile) pipeline built to divert the sewage away from the river ended up in an area where there was no place to build a treatment plant. Now the authorities want more money to return the pipeline to the city.

Then there are the city's struggling silk weavers and handicraft makers, slow to catch up with advances in technology and marketing. There are few jobs.

So, in his first major public meeting here, days before the election on Monday, Mr Modi talked about cleaning up the river, sprucing up the river-front lined by its steep ghats (flights of steps), introducing sight-and-sound shows in the city's historic temples, reviving the weaving industry through "branding, designing, zero-defect manufacturing, quality control".

He promised to make the city a magnet for tourism, "a $3 trillion industry worldwide where profit margins are as high as 40%".

Mr Modi has promised development for the constituency if he is elected...

... but anti-corruption campaigner Arvind Kejriwal is out to cause an upset

Varanasi's famous textile industry is among those suffering from the the effects of modernisation

David and Goliath

In a city of spirituality and faith where time stands still, such unbridled selling of dreams can sound disingenuous. But many say Mr Modi has tapped into the local zeitgeist: a hunger for development, and a belated realisation that the city has been left behind.

After all, the streets of one of the world's oldest cities are also crowded with invitations to join zumba classes, the Arnold Gym, the Jingles Summer camp for children, and the Baba Black Sheep kindergarten school. There is even an advert for a weekend party at a city hotel, organised by Da Evil Group, "for all boys, girls and couples" and promising "enjoyment at its height".

"Development is the only issue in Varanasi," says Dr Vishwanath Pandey, who teaches at the city's famous Banaras Hindu University. "Mr Modi has caught the imagination of the locals by putting the development of the city at the forefront.

"Also, don't forget, Varanasi is trying to regain its place in national politics and sending a prime minister to the parliament is a good way to do it".

Varanasi has woken out of its political reverie and become the battleground for the election's biggest slugfest.

It is an absorbing David and Goliath battle, where Arvind Kejriwal, India's best known anti-corruption campaigner and leader of the new Aam Aadmi Party, is playing David to Mr Modi's Goliath. In a city imbued with symbolism, Monday's poll battle is also deeply symbolic: a political duel between the powerful and the underdog.

The battle for Varanasi, as one commentator succinctly said, external, is between the "larger-than-life personality of Modi and the perceived moral authority of Kejriwal". It could also become a landmark in what promises to be an engaging contest over the future of Indian politics in a city which inspired French observer Francois Bernier to call it "the Athens of the East" for its giddy confluence of ideas.

Varanasi has held huge importance as a centre of Hindu learning and pilgrimage for centuries

Mr Kejriwal's army of young, idealistic supporters armed with brooms (the party symbol) have taken over the streets of Varanasi drumming up support for their leader, singing, marching and sloganeering. His supporters claim he has made inroads in many of the 300 villages that dot the constituency and that Muslims voters who comprise nearly a sixth of its 1.7 million voters are gravitating towards him.

In his campaign, Mr Kejriwal challenges Mr Modi's claims to be an efficient ruler of the "supposedly miracle economy" of Gujarat and challenges him to a public debate.

There is a stealth campaign to undermine Mr Kejriwal. At the rally by Mr Modi, a man went around handing out a shabby, ranting booklet entitled "The Anti-National Kejriwal", linking him to "Americans, Maoists and Islamic radicals", in no particular order.

"Mr Kejriwal has definitely made an impact. He wants to evolve a new system of politics. This has created a connection with people as mainstream parties are seen as corrupt," says Dr Pandey.

Congress shut out?

In the epic battle between the two outsiders, the insider seems to be left behind.

Ajay Rai, a local businessman with a controversial past and a former BJP member, is the Congress candidate.

As the "son of the soil" representing India's Grand Old Party, Mr Rai should be Mr Modi's main rival. But the battle of perceptions has been irrevocably lost, and he appears to be campaigning from a position of weakness.

"Brand Modi is a challenge," an aide of Mr Rai's tells me. "And Kejriwal is creating a lot of noise."

So I ask Mr Rai what he is doing to counter this.

"The outsiders will be a super flop. Only the son-of-the-soil politics works here. I am an insider, I live here, I can look after my city better," he says.

Will Mr Rai cause an upset? Unlikely, say locals. But then, in Varanasi, you also never quite know.

"Anything can happen in Varanasi," says Professor Vishwambhar Nath Mishra, head priest of a renowned temple.

"You have visible and invisible voters. There are spirits here. You never know what the results bring."