The tough task of reviving India's decaying railways

- Published

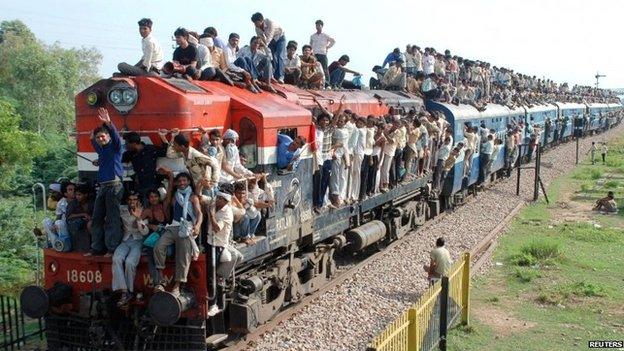

India's railway carries some 23 million passengers every day

As the sun starts to set over India's Udaipur railway station, a female voice on the tannoy system informing passengers of an incoming train fills the hot, humid air.

As the Mewar Express pulls up, there's a sudden, frantic rush.

Before it comes to a complete halt, male passengers throw in their luggage through the train's open windows before diving in themselves, while women in colourful saris and barefoot children hurry through the doors.

Within minutes, the train's unreserved carriages bound for Delhi 740km (459 miles) and 13 hours away are packed full of sweaty passengers with little room to walk.

Some are lucky to get a seat, others have to settle for the floor as the smell of urine lingers from one of the train's open toilets.

Used by around 23 million people each day and covering almost every nook and cranny of India, the state-controlled railways is considered the "lifeline of the nation".

But after decades of neglect, the network is in shambles.

Many problems

It's overcrowded, dirty and outdated and observers say successive governments, unwilling to take bold steps to address its long list of problems, have hampered the growth and development of Asia's oldest rail network.

But with a new administration under Prime Minister Narendra Modi who sealed a landslide victory in May's general election after campaigning on a platform of aspiration and economic reform, the hope is that it could soon change for the better.

To get the state-controlled Indian Railways back on track, analysts say hundreds of billions of dollars of investment is needed over the next decade.

India's railways are considered to be the 'lifeline' of the nation

"Apart from energy, transportation infrastructure is probably the biggest economic growth driver that India can depend on. If you want 7% growth, we have to improve our railways," said G Raghuram, a professor at the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad city.

India's economic expansion has slowed markedly, growing by 4.7% in the 2013-14 financial year and marking the second year of sub-5% growth.

India railways in numbers

India runs 11,000 trains everyday, of which 7,000 are passenger trains

India has 108,706km of railway tracks

23 million passengers travel by trains in India every day

A third of India's rail routes are electrified

Already, the new BJP government, backed by a massive mandate, has put up prices. Last month, it hiked passenger fares by 14.2% and freight rates by 6.5% - a move welcomed by economists.

But there was a partial rollback on some increases on shorter trips following protests, even though Finance Minister Arun Jaitley said the government had "taken a difficult but a correct decision".

"India must decide whether it wants a world class railway or a ramshackle one," he added.

Despite the rise, rail tickets in India remain dirt cheap.

This is because freight rates - among the highest in the world - heavily subsidise passenger fares.

For the entire overnight ride on the Mewar Express, a ticket can be purchased for as little as 200 rupees ($3; £1.75), making it accessible to poorer passengers who cannot afford to travel by other modes of transport.

But the below-cost fares contribute to an annual loss of around $4.5bn (£2.7bn), while the high freight rates mean moving goods by road has become a more viable option.

"Indian Railways is kind of schizophrenic in that the machinery cannot decide whether it is working for profit or to please the public," said a railways bureaucrat who did not want to be named.

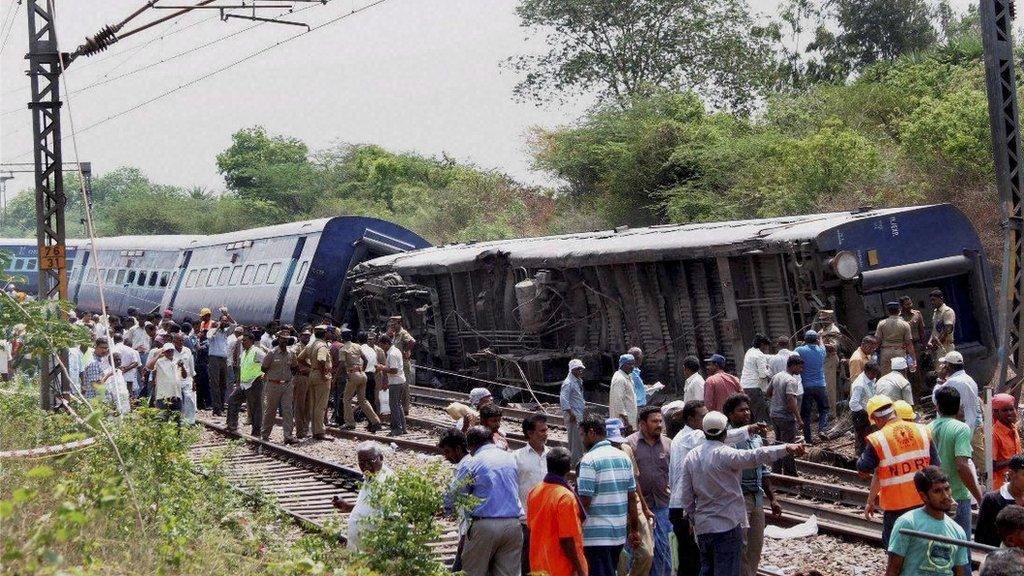

Many people die after falling off trains or while crossing tracks in India

India's railway has a poor safety record

In its election manifesto, the BJP has promised to improve the railways' poor safety record.

Each day, around 40 people on average are killed somewhere on the vast network. Many die after falling off trains or while crossing tracks. Others are killed in collisions, fires or derailments.

Over 40% of accidents occurred because of railway staff failure, according to a 2012 government panel report. It also noted that between 2006 and 2011 a rising number of accidents were due to sabotage.

Another poll pledge of the BJP is to introduce bullet trains linking India's major cities.

Last week, during a test run between Delhi and Agra, the home of the Taj Mahal, a passenger train clocked 160km (99 miles) an hour, setting a new national speed record.

The local media dubbed it a "semi-bullet" train because while fast by Indian standards, it only ran at half the speed of a Japanese Shinkansen (bullet train) which travels at 320km (198 miles) an hour.

Mr Modi - the son of a railway platform tea seller - has said he wants a train to run that fast between Mumbai and Ahmedabad in Gujarat state, but analysts believe this is unlikely to happen any time soon.

Inefficient

Instead, they say more "semi-bullet" trains could appear as early as 2018 when dedicated freight corridors are expected to open between Delhi and Mumbai in the west, and Punjab state and Calcutta in the east.

This will allow existing tracks to be used exclusively by passenger trains that will be able to travel faster than they do today.

With a workforce of 1.3 million people, Indian Railways is one of the world's largest employers. Many hope Mr Modi's government will go the full distance and order a complete restructuring.

To improve performance and combat corruption and bureaucratic inefficiency, a government report released earlier this year by a committee chaired by Rakesh Mohan, executive director at the International Monetary Fund and former deputy governor of India's central bank, called for the "corporatising" of Indian Railways by separating its management and operations from the government.

India carried out trial runs of a high-speed train recently

Mr Raghuram from the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad supports the idea; describing it as a "big ticket item" he'd like to see in Tuesday's rail budget.

"The railway board is extremely inward looking," he said. "There needs to be change in the top management structure. That's very important."

Back on the Mewar Express, the train rolls through north India's countryside on its way to the Indian capital.

Rishabh Sultania, a 24-year-old marketing manager, sits in one of the train's air-conditioned carriages with his laptop. He explained how difficult it was to book his $30 (£17.5) ticket.

"The biggest problem for me is seat availability. The population is increasing so there really should be more trains or they should add more coaches," he said.

Atish Patel is a Delhi-based independent journalist

- Published19 July 2010

- Published10 April 2013