Why India loves to ban films

- Published

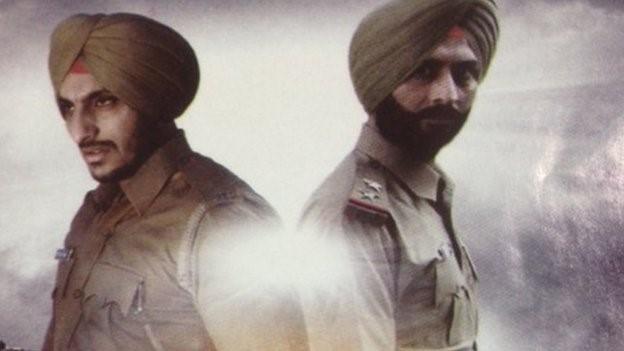

Kaum De Heere (Diamonds of the Community) tells the story of Satwant Singh and Beant Singh, Indira Gandhi's assassins

The move to ban a controversial film on the October 1984 assassination of former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi has a sense of deja vu about it.

This time, the Congress party is up in arms against the Punjabi film Kaum De Heere (Diamonds of the Community), complaining that it glorifies the assassins of Mrs Gandhi, who was shot dead by her Sikh bodyguards for sending the military into the Golden Temple, the community's holiest shrine.

Apparently, intelligence agencies have warned of violence if the film is released - after all, Mrs Gandhi's murder in October 1984 sparked anti-Sikh violence, which killed more than 3,000 members of the community across India.

Congress party leaders in Punjab insist that the film "presents murderers as heroes", a charge that its producer denies, saying that it is just a film about political assassinations.

Many say the Congress party has a record of touchiness when it comes to films involving its leaders and rule.

In 1975, Aandhi (Gale), a film based partially on Indira Gandhi's life was not allowed a full release by the Congress government.

Kissa Kursi ka (Tale of a Throne), a 1977 satire of her and her son Sanjay, was banned by the government during the Emergency - when civil liberties were suspended - and the prints destroyed.

Eight years ago, the Congress party served a legal notice, external to the makers of a proposed film on the life of party leader Sonia Gandhi, fearing that it would contain inaccuracies.

"Political leaders are seen as holy cows. They cannot be criticised in films," says film critic Shubhra Gupta.

That's not all. There have been demands to ban films in India for as long I can remember.

In 1994, Shekhar Kapur's Bandit Queen, based on the life of Phoolan Devi, was banned for its rape scenes and profanity. Next year, Mani Ratnam's Bombay, a searing film on the religious riots in the city, ran into problems with Hindu right-wing groups calling for a ban.

In 1998, the same groups attacked screenings of Deepa Mehta's Fire for showing a lesbian relationship. In 2000, Hindu fundamentalists trashed the sets of Mehta's film, Water, in the holy city of Varanasi, arguing that the film tarnished the city and denigrated Hindu traditions. Mehta reshot the film with a new cast in Sri Lanka.

Kamal Hasan's big budget spy thriller Vishwaroopam ran into problems when some Muslim organisations found that its portrayal of the community was unflattering, provoking a censor board member to say it was "cultural terrorism". Hasan finally agreed to excise some portions of the film. A few years ago, a group of barbers protested against a film called Billu Barber, because they found the word barber derogatory. The film had to be renamed Billu.

Social scientist Shiv Visvanathan says frequent calls to ban films are part of a broader malaise in a country where "a lot of people have made their careers in sensitivities".

"There are fringe groups in India which mobilise people around issues of obscenity, dirty movies, dirty pictures," he says.

Political parties like the Congress are particularly touchy, he says, about films that "challenge their folklore". National leaders cannot be criticised, and the violation of the official narrative is frowned upon.

"This is a new kind of a tacit and explicit censorship," says Mr Visvanathan.

For a country which boasts of one of the world's biggest film industries - critics accuse Bollywood of mainly peddling fantasies which largely avoid the grittier and more controversial realities - this is a disconcerting thought.

"India," Mr Shiv Visvanathan says, "is becoming a intolerant society."