Why the riots in Delhi's Trilokpuri are significant

- Published

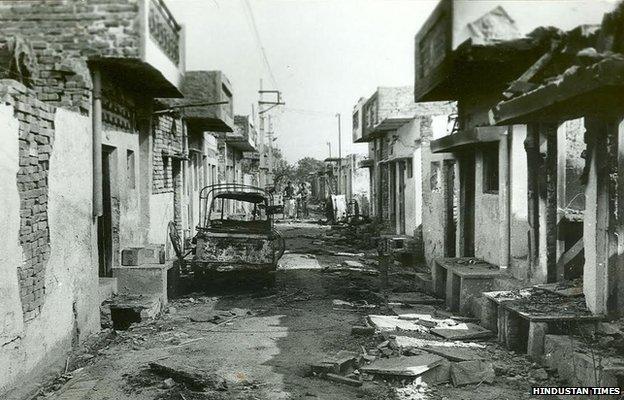

A clothes shop owned by a Muslim was burnt down in the riots

Last week's clashes between Hindus and Muslims in Trilokpuri, external in Delhi did not exactly become headline-grabbing news.

Residents - helped by, many say, outsiders - fought pitched battles on the streets with stones and bricks, torched a couple of shops, threatened each other and vandalised property. Thirty-five people were injured. Five people sustained gunshot wounds as the police fired to rein in the rioters. More than 60 people were arrested.

Why we should pay attention to the violence in Trilokpuri?

Historian Mukul Kesavan says one reason is that "history of communal violence in India demonstrates that it is closely connected with turning points in high politics", external. In this case, it happened months after the Hindu nationalist BJP swept into power in Delhi with a historic win. There is not a shred of evidence to link the party to the violence but Mr Kesavan wonders whether "Hindu activists are testing the waters, testing the limits of the politically possible in the wake of the election".

Trilokpuri in east Delhi is not your average, nondescript Delhi neighbourhood.

It began as a home for socially deracinated, poor and disadvantaged people who were cleared out of their homes during a slum-cleaning drive by the Congress government during the Emergency, external in 1976. The neighbourhood gained a notorious reputation as a religious tinderbox in 1984 when it witnessed one of the worst episodes of the anti-Sikh riots, external - 350 of the more than 2,700 Sikh victims were killed here.

Congested

Today, the neighbourhood has settled into a chaotic, but largely peaceful middle age.

It's a bustling, untidy, low-rent, high-density, congested urban sprawl dotted with low slung homes breathing down on each other in claustrophobically narrow streets. Trilokpuri also supplies Delhi and its neighbouring suburb of Noida with its masons, carpenters, housemaids, guards, factory workers and assorted blue-collar workers.

Trilokpuri was rocked by anti-Sikh riots in 1984

Old, grotty homes are being torn down all the time, and replaced with newer structures. Hence, a lot of bricks and stones line the roads which the rioters found handy as missiles.

Some 150,000 people - mainly Dalits (formerly known as untouchables) and Muslims - live in its 36 "blocks" or clusters. Every block has a small park - there's one even reserved for women. There are more than a dozen government-run schools and a dispensary. A tiny one-room rents for up to 3,500 rupees ($57; £35), and an apartment can cost more than 3m rupees ($48,892; £30,545). Property prices, locals gloat, will rise further when the Delhi metro zips through the area.

There are restaurants, beauty parlours, shops selling everything from clothes to mobile phones and branded shoes. Itinerant vendors push carts selling vegetables and snacks. Water and electricity, say residents, is plentiful. Hindus and Muslims, locals and migrants, have lived cheek-by-jowl for decades without stepping on each other's toes. To describe Trilokpuri as a religious tinderbox today is to undermine its hard-working, tolerant people.

Of course, it has its problems.

In many ways, Trilokpuri exemplifies what is right and wrong with a fast urbanising India.

There are mobile phones ("Android mind you," says a local boy), refrigerators and cable TV even in the poor one-room slum homes. But the quality of education is poor - local schools are overcrowded and teachers are often absent - and most young men and women fail to obtain the absurdly high marks the colleges in Delhi demand to qualify for admission. So most of them end up doing college by correspondence with dim job prospects. Many drop out to earn for their families when their parents lose their uncertain, unskilled jobs. The jobless and the hopeless drink, gamble and fight.

"We are restless, we are aspiring, but the future looks uncertain because we don't have opportunities, we don't have a head-start. So there's a lot of confusion among the young," says 18-year-old Suraj, who wants to become a journalist.

Drunken brawl

Last week's violence began after a drunken brawl on Diwali night outside a temporary Hindu roadside shrine put up under a tent by locals in an empty space hemmed in by houses.

The shrine was put up barely 50 metres away from a 38-year-old local mosque and, by all accounts, the incessant blaring of music from giant speakers put up at the shrine was disturbing the mosque prayers. There is no clarity on what sparked off the fight between a group of Hindus and Muslims near the shrine. Right across the mosque is an old Hindu temple and, according to Zainul Abedin, a local fruit-seller, the two have co-existed without any conflict.

There is tight security in the area

Hindus and Muslims have lived together in the area for decades

By all accounts, the violence began next morning after rumours flew heavy and fast by word of mouth, mobile text and a popular instant messaging service.

Many Muslims say former BJP legislator Sunil Vaidya instigated the rioters, a charge he strenuously denies, external. A Muslim-owned two-storey clothing shop was set on fire. Flickering mobile phone videos of the rioting show young men in jeans and sneakers and wearing shiny motorcycle helmets throwing stones, bricks and bottles across a road. There are no war cries, only a low hum of anger.

Muslim residents say the police looked the other way initially, letting Hindu mobs vent their fury, and even damaged some taxis owned by Muslims. Hindus say the Muslim mobs fought heavily. "I have never seen anything like this in my three decades of living here. Hindus and Muslims have lived here peacefully. I thought we had left the riots behind," local legislator Raju Dhingan of the Aam Aadmi Party told me.

A week after the violence, Trilokpuri's streets are still tainted with red brick dust and broken glass, its people are scared and cooped up in their homes on orders of the police, deprived of their work and daily wages. Many have left their homes. Nobody quite knows how and why a drunken fight escalated into religious violence. "I don't know what is happening here," says Shaukat Ali, a plumber. "I am afraid, very afraid."