Why India tea workers are agitated

- Published

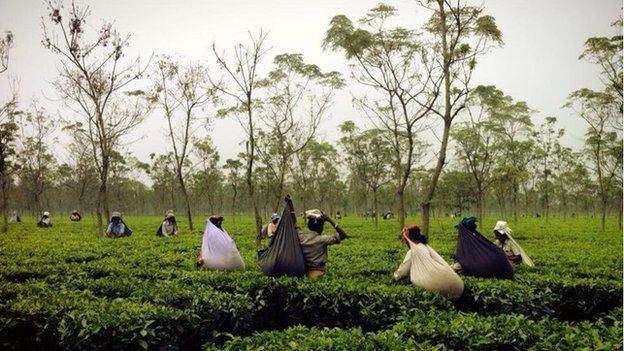

Conditions for tea plantation workers in India can be terrible, as Sanjoy Majumder reports

India is home to world famous tea brands such as the Darjeeling variety, grown in the Himalayas. But plantation workers on the plains further south, where tea for the domestic market is grown, often live in terrible conditions, as Sanjoy Majumder reports from Jalpaiguri in north Bengal.

There's an eerie silence at the Sonali Tea Estates, a sprawling plantation in north Bengal's Jalpaiguri district, at the foothills of the Himalayas.

The owner's bungalow is empty and there are no workers to be seen anywhere.

Last week the owner, Rajesh Jhunjhunwala, was dragged out of the two-storey whitewashed building by angry workers and beaten to death amid the tea bushes.

The murder has sent shockwaves through the tea-growing community.

"This attack is completely unprecedented," says UB Das, secretary of the Terai Planters' Association.

'Demoralised'

"We are all demoralised and everyone is nervous about their safety."

The homes of the workers', located just outside the gate, are also deserted. Some of the women have collected outside. There's tension in the air.

"The police came at night and took away several of our men," says one woman.

"We fled into the jungle and spent the night there with our children."

Others complained that they hadn't been paid in months.

"We don't get anything - no rations, medical aid nothing. How are we expected to survive?"

At the root of the conflict is economics.

Life has been hard for Sumari Oraon after the tea estate she worked for closed down

Unlike the globally famous Darjeeling tea which is grown in the mountains further north, these plantations are located in the plains producing cheap tea mostly for the domestic market.

"Other tea-growing countries have come up so our exports are dwindling," says Mr Das.

"Margins are tight because production costs have escalated. Some gardens have shut and many owners have defaulted on their dues."

The massive iron gates of the Bandapani Tea Estate are shut - it closed down in 2012, one of five estates that stopped operating in the region.

The factory buildings are abandoned, rusting machinery can be seen inside with only a few stray cattle for company.

This estate once employed more than a thousand people. Now they're all out of work.

Despair

The small colony housing the tea workers is only a short distance away. New Pucca Lines was set up by the British along with the plantations, more than 150 years ago.

Now there's a distinct air of despair and deprivation.

The tin roofs of some of the houses are broken, others have no windows or doors. There are hardly any men about.

"They've all gone to look for work," says Radhika Thapa.

"Only the ones who are sick are left behind."

Sumari Oraon is sitting outside her home, sifting through some grains which she'll cook for lunch.

In her sixties, she looks considerably older, her hair completely white and her face lined with wrinkles.

The gardens in Jalpaiguri have fallen upon hard times

"Ever since the tea estate closed it's been so hard," she says.

"We have so little food and I have to divide it between my two grandchildren. How will their stomachs ever be filled?"

Over the past few years, a number of tea workers have died. There is a debate over whether they've died because of malnutrition or other causes.

Victor Das, a local social worker, says there are many reasons why workers are dying.

"If they don't get paid, they have no money to buy food because of which they are malnourished.

"They fall ill and often die as a result."

Set up by the British in the 19th Century, these plantations have supported and sustained entire generations of tea growers.

All that has changed now - and many of them are faced with extreme poverty and, in some cases, death.

- Published23 November 2014