Why India’s mobile network is broken

- Published

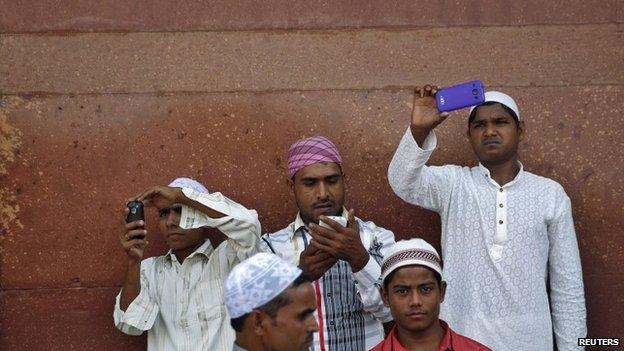

Call drops are common on India's mobile phone network

Claire Verhagen's first encounter with India was at the end of November when she landed in Delhi and switched her phone on.

"I tried every network repeatedly for 15 minutes," she says. "I finally connected to Airtel. I got a full signal, but I couldn't call. I borrowed another passenger's mobile to call my hosts."

She had better luck on the drive to her hotel. She managed to call her husband in Belgium. The call dropped twice, though.

For a generation of Indians brought up on mobile phones - many of them haven't ever used a landline - poor call quality and call drops are part of life.

It wasn't always so.

Problems

When the mobile phone came to India in the mid-1990s, call quality was good. Mobile service quality was better than landlines, and dropped calls were rare.

There were few subscribers, and the service was expensive - up to 16 rupees (about $0.25 today) every minute.

Fast forward to today, when calls are 20 times cheaper, and mobile telephony powers the economy, with 915 million mobile subscriptions. Every second Indian carries a handset.

Here's what those mobile phone users deal with every day:

Can't connect: Connecting when "roaming" can be a struggle. If your flight has just landed, several hundred devices power on and try to connect to an overloaded network. On a train, users find it difficult to hold a conversation even when passing through areas with moderate cellular coverage. It's the same on inter-state highways.

Network busy: You have a full signal, but can't call - common in busy areas such as Delhi's airport, Gurgaon's Cyber City (an office area near Delhi), and elsewhere in India's large metros. Many users keep retrying on auto-redial, which adds to the problem.

Call drops: When you, or the person you're calling, are on the move, it's common for the call to drop. Often, both of you will try re-dialing, and fail to connect. If one of you moved into an overloaded network area, you may not be able to reconnect easily.

No internet: Mobile data is patchy in India. 3G isn't everywhere, but even where you get a strong 3G signal, you might find no data activity. This is a problem for a country with 240 million mobile internet subscribers - that's 92% of its total internet subscriber base.

Poor signal: A weak mobile signal is common in urban India's high-rise office and residential areas. The upscale condominium complex in Gurgaon where this writer lives has virtually no mobile service.

India has roughly 900 million mobile phone subscribers

So why is the mobile network powering modern India so broken?

"The top three reasons are spectrum, spectrum and spectrum," says Shyam Mardikar, chief of network planning and strategy for India's top mobile operator, Airtel.

Spectrum, the radio waves that carry phone signals along with television, radio and all wireless communications, is a scarce resource that's controlled globally by governments.

India allows relatively little spectrum for mobile communications, and splits that up among a dozen operators. A lot of radio spectrum is blocked for defence use.

How bad is the spectrum crunch?

Sample this: Delhi's top operator has roughly the same number of 3G users as its counterparts in Singapore and Shanghai (about 3 million), but it has about a tenth of their spectrum.

And that's the problem, Mr Mardikar says.

Towering Crisis

A spectrum auction is on the cards in 2015, but the government will largely re-auction "expiring" spectrum now held by top operators Airtel, Vodafone, Idea and Reliance.

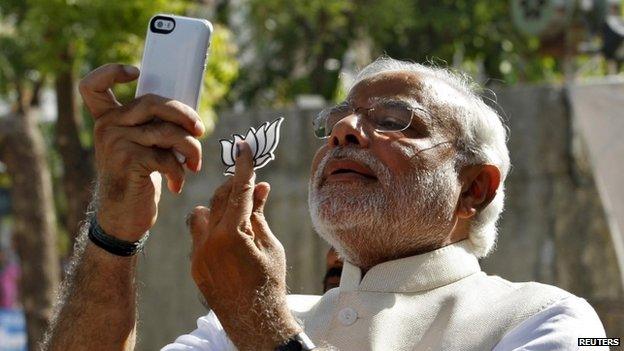

In an open letter to India's telecoms minister in late November, the global GSM Association chief Anne Bouverot said the spectrum crisis threatened Prime Minister Narendra Modi government's Digital India, external vision.

Telecom towers, with their antennae, are the ubiquitous symbol of mobile telephony in India, yet there are too few of them with just 425,000 for the entire country.

The spectrum crisis threatens Narendra Modi's Digital India vision

The Tower and Infrastructure Providers Association (Tipa) says India needs at least 200,000 more.

But towers take up real estate, and there are mounting fears about radiation , externaland its health hazards. Protests in residential areas have resulted in towers being pulled down, affecting mobile service quality.

Telecom industry experts protest the "misinformation" about radiation, saying that towers in India exceed World Health Organisation (WHO) safety standards.

They point out that shutting down towers increases radiation from handsets, which then transmit at higher power due to weaker signals from distant towers.

India's telecom user profile adds to network stress.

Nine out of 10 are pre-paid users, with a monthly billing of less than 120 rupees ($1.9), one of the lowest in the world - but they have high expectations and low patience.

When they're unable to connect, they keep redialling, which keeps the network busier.

Those user numbers will grow - faster than spectrum availability. And more people will use data, especially video, stressing the network further.

Will things get better?

Off the record, industry insiders say: No.

India's mobile network experience will probably get worse in the near future.

Prasanto K Roy (@prasanto) is a technology analyst in Delhi

- Published13 February 2014

- Published12 February 2014

- Published3 February 2014

- Published11 December 2013

- Published16 June 2013