Africans in India: From slaves to reformers and rulers

- Published

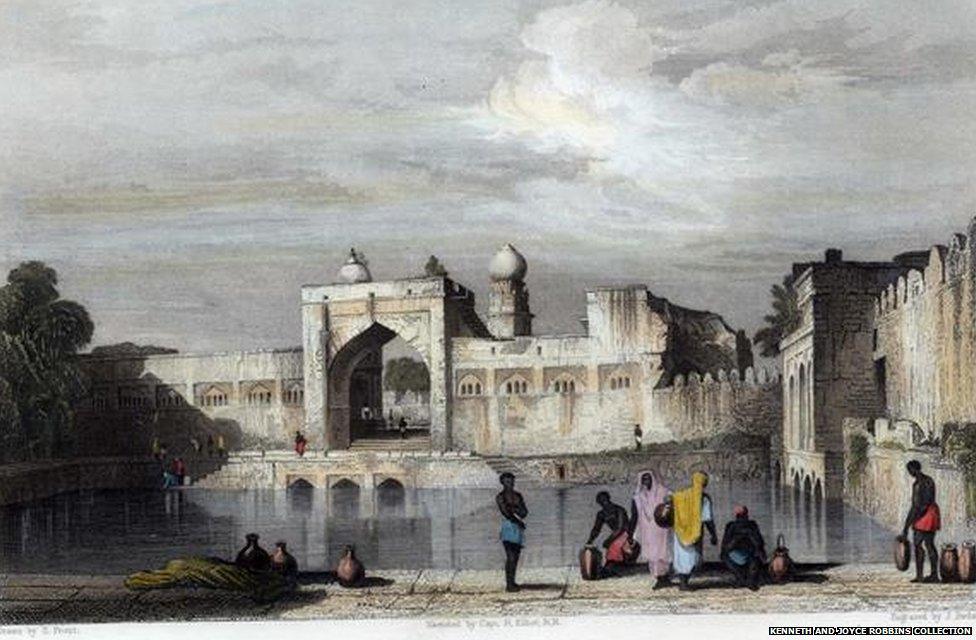

This painting shows a reservoir built by an Abyssinian eunuch in the 17th Century

India and Africa have a shared history in trade, music, religion, arts and architecture, but the historical link between these two diverse regions is rarely discussed.

Many Africans travelled to India as slaves and traders, but eventually settled down here to play an important role in India's history of kingdoms, conquests and wars.

Some of them, like Malik Ambar in Ahmadnagar (in western India), went on to become important rulers and military strategists. Ambar was known for taking on the powerful Mughal rulers of northern India.

An exhibition, organised by the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture of The New York Public Library, in Delhi recently showcased such "forgotten" stories of Africa's role in India's history.

Abyssinians, also known as Habshis in India, mostly came from the Horn of Africa to the subcontinent. Dr Sylviane A Diouf of the Schomburg Center says Africans were successful in India because of their military prowess and administrative skills.

"African men were employed in very specialised jobs, as soldiers, palace guards, or bodyguards; they were able to rise through the ranks becoming generals, admirals, and administrators," she says.

Kenneth Robbins, co-curator of the exhibition, says it is very important for Indians to know that Africans were an integral part of several Indian sultanates and some of them even started their own dynasties.

"Early evidence suggests that Africans came to India as early as the 4th Century. But they really flourished as traders, artists, rulers, architects and reformers between the 14th Century and 17th Century," he says.

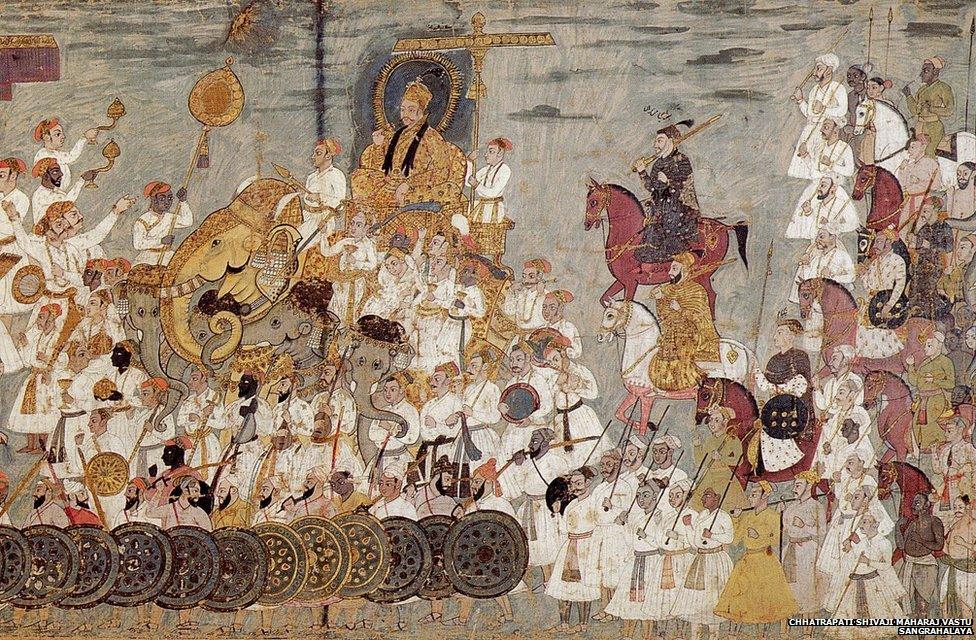

This 17th-Century cloth painting depicts a procession of Deccani sultan Abdullah Qutb Shah. African guards are seen here as part of the sultan's army.

Apart from the Deccan sultanates in southern India, Africans also rose to prominence on the western coast of India. Some of them brought their traditional music and Sufi Islam with them.

Mr Robbins says Deccan sultans relied on African soldiers because Mughal rulers of northern India did not allow them to recruit men from Afghanistan and other central Asian countries.

This 1887 painting from Kutch portrays the Sidi Damal, a religious, ecstatic dance form of the Muslim Sidis who were brought to India from East Africa.

Dr Diouf says Indian rulers trusted Africans and their skills. "It was true, especially in areas where hereditary authority was weak and there was ongoing instability due to struggles between factions like in the Deccan," she says.

"Africans sometimes did seize power for their group like they did in Bengal - where they were known as the Abyssinian Party - in the 1480s; or in Janjira and Sachin (on the western coast of India) where they established African dynasties. They also took power on an individual basis, as Sidi Masud did in Adoni (in southern India) or Malik Ambar in Ahmadnagar (in western India)," she adds.

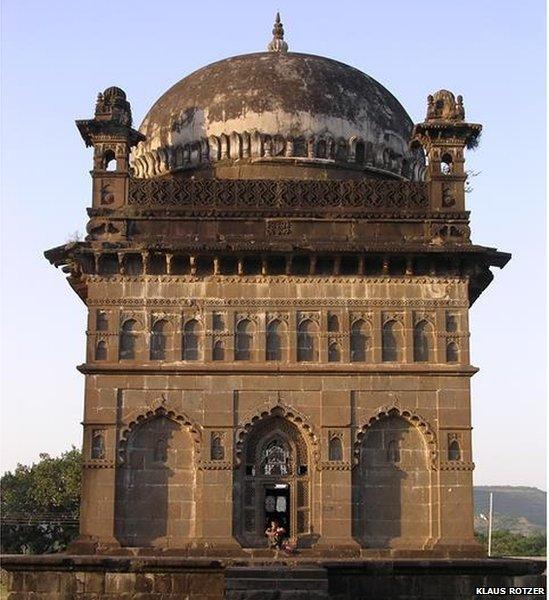

The funerary complex shown in the photograph above was also designed by eunuch Malik Sandal after 1597 in Bijapur (in present-day southern Karnataka state).

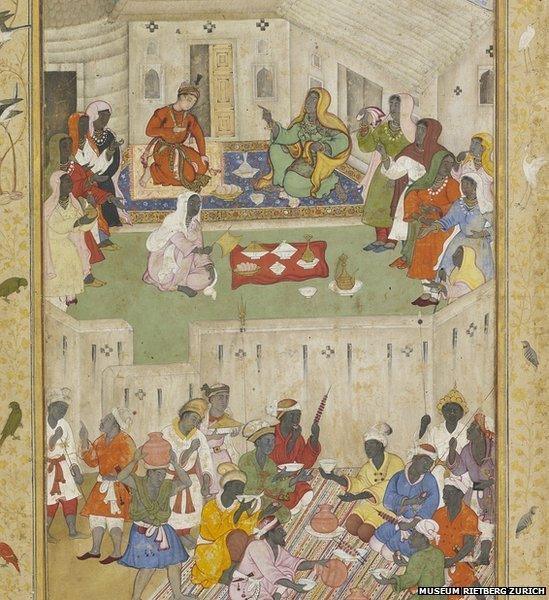

This painting from 1590 shows an Indian prince eating in the land of Ethiopians (Habshi) or East Africans (Zangis).

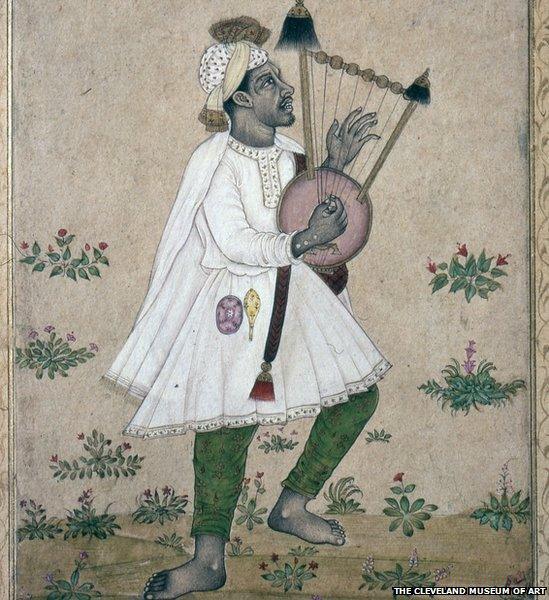

Africans also brought their music to India. This artwork dated 1640-1660 shows a player of the African lyre.

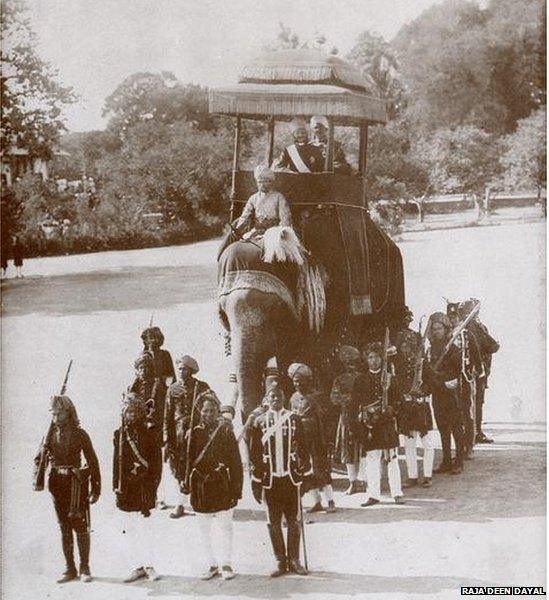

In this 1904 photo taken in Hyderabad in the Deccan region, Africans guards are seen escorting a royal procession.

The most celebrated of the powerful Ethiopian leaders in India was Malik Ambar (1548-1626). His mausoleum still exists in Khuldabad, near Aurangabad district in western India.

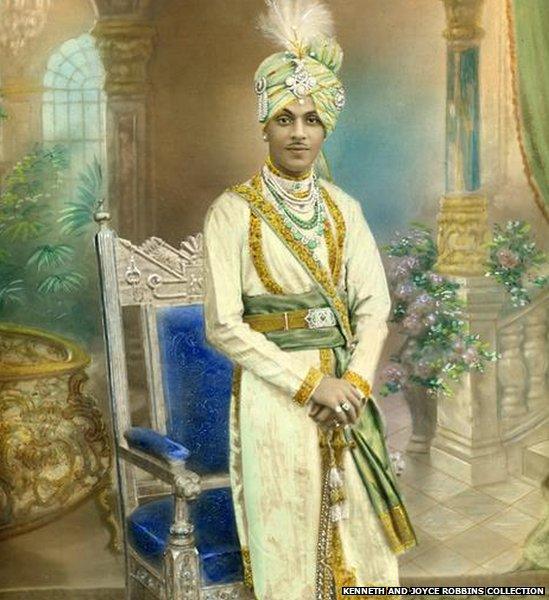

This painting shows Nawab Sidi Haidar Khan of Sachin. The African-ruled state of Sachin was established in 1791 in Gujarat. It had its own cavalry and a state band that included Africans, its own coats of arms, currency, and stamped paper. In 1948, when the princely states were incorporated into independent India and ceased to exist, Sachin had a population of 26,000 - 85% Hindu and 13% Muslim - explains Dr Diouf.

The main African figures of the past have not been forgotten but their ethnicity has been erased, consciously or not, she adds.

"The people who have heard of Malik Ambar, for example, generally do not know he was Ethiopian. Does it mean that these men's origin was so irrelevant that it was useless to mention it, or is this historical erasure the product of a conscious denial of the African contribution?" she asks.